Picasso Guitars 1912-1914, on view at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) through June 6, 2011, is an intense and thrilling experience for anyone concerned with art and visual thinking in the early 20th Century. What it reveals, at least to someone who has worked and thought in three dimensions, are Picasso’s first, profound experiments with one of the key concepts of Twentieth Century plastic arts: negative space. Moreover, the exhibition indicates that like abstraction, for which music was both inspiration and justification, Picasso’s interest in negative space grew out of thinking about music; not musical form and language, but music production– specifically, Picasso’s response to the negative space of the interior of stringed instruments which is the source of their sound.

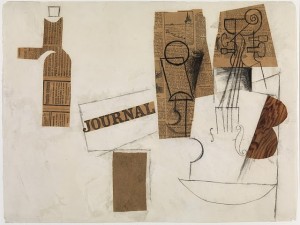

Negative space is an oxymoronic term, but the one commonly employed in all art foundation courses and much criticism. It refers to the space around and between forms — the intervals, rather than the space occupied by matter — when that space is activated as a compositional element. Negative space is a 20th century concept, despite the fact that we tend to view earlier periods, such as the Baroque, through it’s lens. It is essential to 20th century sculpture and architecture and to two-dimensional art by analogy, in concerns with figure/ground relations (as in the remarkable collage below). Despite my asking half a dozen scholars of modernist art and architecture, none could readily cite the term’s first use; this is obviously a subject for further research.

Guitar (1912) shows Picasso’s reification of the negative space of the guitar’s hole as a cone and his use of the space within the body of the instrument as the core of his sculptural form. The fact that a guitar’s body is bounded by parallel planes must have been particularly suggestive to Picasso, who peeled off the instrument’s front and varied the depth of the sides, which he retained. He scooped out the guitar’s neck and defined the plane of its face with frets, indicated by crudely-knotted strings. The first guitar of 1912, made of paperboard, paper, string and wire, is so simple in its means of construction that it might be a recent children’s school project.

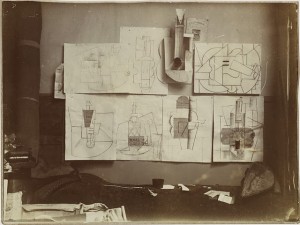

MoMA’s exhibition is beautifully-installed in a single, large gallery and is the ideal size for such a focused subject. Organized by Anne Umland, it spans Picasso’s cardboard Guitar of 1912, the sheet metal version of 1914, and more than fifty related drawings, collages and paintings he created during those two, exceptionally fertile years. Fascinating photographs of the cardboard guitar surrounded by differing groups of drawings and collages in the artist’s studio, indicate Picasso’s simultaneous use of two and three dimensional media in working through his ideas; also on view is a small image of the construction, situated within a still life composed of drawn and found elements, published in Les Soirées de Paris in 1913. This reproduction was the source of Guitar’s renown for almost seventy years.

This brings up the fact that the cardboard guitar was not a fixed and stable object. It was shown hanging above a varying group of drawings and collages in a series of photographs of 1912, but when published in1913 the guitar rested upon the sliver of a cardboard tabletop which cantilevered from the wall, as it did, surrounded by further elements, in a still later photograph of the artist’s studio. The cardboard construction functioned, then, as did the works on paper that Picasso pinned and re-pinned to the wall around it – as a means of working through variants of ideas.

Picasso disassembled the cardboard Guitar and tabletop and packed them away in 1913, not to be seen again until after his death. The artist left the work to MoMA, to whom he had already donated the sheet metal version; the Museum considered the cardboard Guitar a maquette for the metal version. When MoMA reassembled and publicly exhibited it, in 1980, it was the instrument alone (see first image, above), as it had been translated in metal.

The renewed understanding of the cardboard Guitar as part of a still life grew out of the research of University of Pennsylvania art historian, Christine Poggi. Following her study of the photographs, she raised questions which prompted MoMA’s rediscovery of the tabletop and its re-attachment. She also forced a re-consideration of the cardboard version as an independent work, rather than a maquette. In fact, the sheet metal version retains signs of construction that were a function of the original cardboard, such as the cut and splayed-out bottom of the cone used to attach it to the board behind. Were that only a necessity of the cardboard used in a study, Picasso could have welded the metal cone in place.

My focus on the cardboard Guitar is not intended to diminish the interest of the drawings, collages and paintings in the exhibition. They also reveal Picasso’s intense study of space and the definition of forms, in two as well as three dimensions, and his play with mimesisas well as linguistic and associative means to invoke objects. They display a tremendously varied paint application which anticipates that of so many later artists: the splattered paint in Bottle and Wineglass (1912), Bischofberger Collection, simulates marble but also prefigures Surrealism and Pollock; the thick paint applied with a palette knife in Guitar, Gas Jet, and Bottle (1913), Edinburgh, which pulls away from the lower paint resembles remarkably-similar effects in Gerhard Richter’s large abstractions; and the inclusion not only of sand but of thick gobs of paint scrapings in Violin Hanging on the Wall (1913), Kunstmuseum Bern, approaches the rawness of Dubuffet.

Perhaps the most startling and inventive of Picasso’s paint effects is his use of paint as if it were an element of collage. His technique is so mysterious that I inquired about it to Scott Gerson, the conservator who worked on the exhibition. Were those areas of paint, applied with a palette knife, painted on paper then cut and pasted to the canvas, applied directly to the canvas using stencils, or painted on the canvas and then trimmed with a knife? He told me the conservation department had investigated and failed to find a definitive answer. Never mind; Picasso clearly intended the paint to look as though it was collaged, and in 1913 that must have been even more anarchic than it is today.

The exhibition is accompanied by a handsomely-designed catalog (ISBN: 978-0-87070-794-0) which includes an essay by Anne Umland about the history of the works in Picasso’s studio, as published, and their subsequent history. She does not attempt a serious critical understanding of their iconography or place within the artist’s oeuvre, which have received considerable attention, as the bibliography indicates. All of the works are well-illustrated, as are photographs of the cardboard guitar, with and without the tabletop, in the artist’s studio and home; the catalog also illustrates a number of related pieces that could not be lent. The reproductions are generally very good, particularly several enlarged details and the end-papers, which convey the matte and textured surface qualities of Picasso’s experimental paintings, although reproductions are never good at indicating the effect of the pins that hold several of the collages together, forever suggesting their provisionality; this can only be appreciated in front of them. MoMA is planning to produce an e-book following the close of the exhibition that will draw upon an understanding gained from seeing the works together.

* All images © 2011 Estate of Pablo Picasso