Flying over snow-covered mountains in western Pennsylvania long ago, I was struck by the ambiguous appearance of this wintry landscape, as viewed from 30,000 feet. Was I looking at mountains—or and dunes in the desert, waves in the ocean, ripples in a pond? Chad Gerth’s urban photographs and Lydia Jenkins Musco’s constructions of urban materials [Tiger Strikes Asteriod, February 4 – 27, 2011] both explore the difficulties the eye faces in making sense of the world.

Gerth’s photographs of vacant lots in Chicago make clever use of such uncertainty. A recent M.F.A. graduate from the Art Institute of Chicago, the artist went to impressive lengths to make his images, hiring a camera-equipped drone helicopter to hover above desolate parts of the city. Viewing flat parcels of land straight on from a distance of approximately 80 feet above, depth and scale suddenly evaporate. Are we seeing tall grass on ground, or fuzzy moss on wood?

Glancing at the work on the walls, you might miss the fact that two of the images represent the exact same lot. They are both titled Division & Spaulding, but their appearance is different in every respect. Photographed at mid-day, a vertically-displayed view of this location shows an even bright green covering and could easily have been called View inside a Terrarium. In a horizontal version, much of the lot is in shadow, and different lighting reveals different details. Fence posts along the outer edge of this long rectangle resemble the diagonal hashes that once bordered airmail letters. A set of grassless tire ruts form a kind of mysterious writing on that envelope. The artist reminds us that each photograph is its own object, independent of what was photographed.

Every one of Gerth’s images, in fact, is rich with graphic detail. Without vertical reference points, shadows read as flat diagonals. Tire tracks in gray sand in Lake & Costner look like the frenzied scribbles of a child as she draws the same circle over and over. In Chicago & Avers, cracks in a cement slab form a rectangular grid that resembles a miniature street grid. The alternating pink-and-black parquet from a leftover patio supplies a splash of warm color amidst green and gray. Lifted from the most mundane of urban realities, these images are quite pleasing as abstract art.

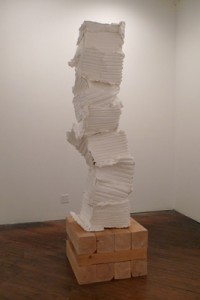

If Gerth’s images turn reality into drawing, Musco’s sculptures make the immaterial concrete—literally. Also a recent M.F.A. graduate (Boston University, 2007) Musco was the recipient of a Pollack-Krasner award for sculptures that play with architectural forms and hard-soft dualities. What seems like a tower of mortar-caked terracotta tiles in Surrounding Walls is actually molded paper pulp. Adding to the deception is the stack of thick timbers that serves as the sculpture’s plinth—as if paper needed a heavy-duty support. In Three-sided Square on Four Walls the same paper pulp poses as a heavy pile of felt sheets, each in a different shade of pink or red.

What is most satisfying about Gerth’s photos is that they transcend the game of disguise that is the basis of their creation. The process of discovering tire tracks, poles, and grass that makes for good visual fun in Gerth’s work also reveals of years of fighting between humankind and nature. The art is not only about how humans form a concept of their world, but also the struggle between human conceits and the natural surroundings that always seem to get the better of them.