The Making of Art (Buchhandlung Walther Koenig: Cologne, 2009) ISBN 978-3-86560-586-3

Target Practice; Painting Under Attack 1949-78 (Seattle Art Museum, 2009) ISBN 978-0-932216-64-9

Those of us involved in the art world never seem to tire of looking critically at the way that world works. Self reflection has been the basis of a number of exhibitions in recent years; I saw two devoted to artists’ studios: The Studio at the Dublin City Gallery The Hugh Lane (discussed on Jan. 3, 2007) and Picturing the Studio at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (2009-10). The Making of Art, at the Schirn Kunsthalle, Frankfurt and Target Practice; Painting Under Attack 1949-78 at the Seattle Art Museum, addressed further aspects of art production, circulation, and valuation. While I saw neither of them, given their thematic nature their catalogs offer significant interest and are likely to be particularly appealing to art world insiders. Simply studying the illustrations is bound to provoke fruitful associations, dialog and argument.

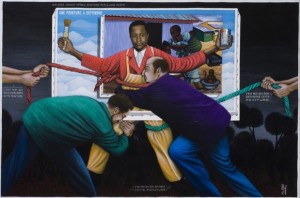

The Making of Art addresses the broader topic and includes artists working beyond Western Europe and the U.S.. While there’s a Piero Manzoni of 1963 (Merda d’artista) and several works from the 1970s, most dates from the past two decades. The artists selected question art production, the special role accorded the artist (and, indeed, artists’ role models) and most aspects of the art market including the proliferation of art fairs; they conduct broad institutional critiques and analyses of the way art’s presentation creates meaning; and they investigate art’s subject, authorship, and standards of art world success. Some idea of the range is encompassed in the title of Wolfgang Ullrich’s catalog essay: Art as the Sociology of Art.

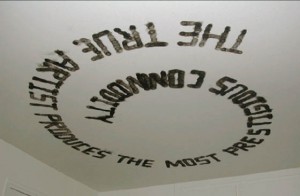

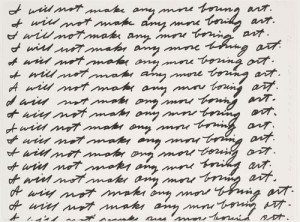

John Baldessari’s early works using language to interrogate art world practices are well-known and feature in both exhibitions discussed here. Other work is less familiar: a jab at the commodification of dissent by the anonymous collective working under the pseudonym, Claire Fontaine, in True Artist (Spiral Version) (2004/09), a spiral of words a la Bruce Naumann, written in smoke on the ceiling; in the video, Portrait With a Curator (2002), four Polish artists who collaborate under the name Azorro have themselves filmed in various art world settings, then circle the image of a curator in attendance (always in the background and oblivious to the artists) as a way of underlining the function of networking in creating and sustaining artists’ reputations; Anetta Mona Chisa and Lucia Tkácová perform acts of petty theft as attacks upon the commercial art world, then display (and sell) their spoils, with provenance indicated, in the gallery which represents them; commenting on his video, MoMA Visit (2009), documenting a trip to China by MoMA’s International Council, Ai Weiwei includes the statement: In 1986 I wrote “If a person can walk into MoMA and not feel ashamed, it can only mean either that his senses are compromised or his morality is wanting. MoMA is a place full of prejudice, power and vanity.” … I still believe what I wrote then.

Andrea Fraser gets to the heart of many artists’ objections to the market with Untitled, 2003 in which she offered a sexual encounter (with various specifications) at a fixed price through her gallery. If selling one’s work amounts to prostitution, Fraser doesn’t offer a less compromised way to put food on the table, and one suspects she’s never been through the process of applying for tenure in an art department.

Target Practice; Painting Under Attack 1949-78 addresses an art form that might long have claimed, as did Mark Twain, that news of its death was an exaggeration. The attack on painting was carried out in a variety of media and the exhibition was flexible in the examples it chose (both in textual illustrations and for the exhibition), including Rauschenberg’s Erased de Kooning Drawing (1953), Shigeko Kubota’s performance, Vagina Painting (1965), Lygia Pape’s communal action, Divisor (1968), Bruce Nauman’s photographs, Art Make-Up (1967-68), Dan Flavin’s fluorescent light works, and Baldessari’s video, Six Colorful Inside Jobs (1977).

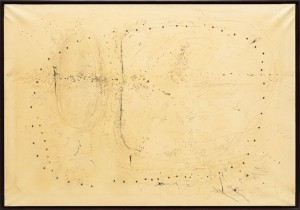

The exhibition’s argument begins with extensive attention to Lucio Fontana, who punctured the canvas in the late 40s (ignoring the fact that Miro had done so more than twenty years earlier, although to little attention) and places a significant emphasis on the role and manipulation of the canvas in the history of attack it explores. These attacks on the canvas include work by Alberto Burri, Howardena Pindell, Linda Benglis (knots), Piero Manzoni (bandaged-looking Achromes), Nikki de San Phalle (a photograph of her shooting at a painting with a .22 rifle is on the catalog’s cover), Shozo Shimamura and other Gutai artists, and Sam Gilliam, who hung stretcher-less swags of canvas.

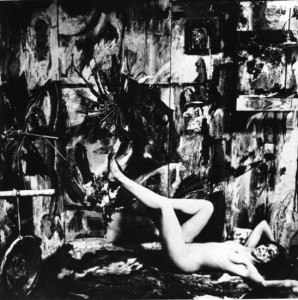

The exhibition was an occasion for the Seattle Art Museum to feature works in its collection, and combined with the practicalities of loans that may well have resulted in a narrower exhibition than the curator, Michael Darling, would have liked. Even so, some omissions are particularly surprising, and the range of his essay might certainly have been expanded. The perfunctory attention given Yves Klein is baffling, as is the omission of Warhol’s use of screen-printing as painting (although one of his small group of piss paintings is included). Darling ignores the racial politics that likely figured in the attack on painting’s status quo by Sam Gilliam and Al Loving, as well as the use of humor as intellectual attack by Robert Colescott. And he left the feminist critique particularly under-explored; works such as Carolee Schneemann’s Eye Body (1963), Eleanor Antin’s Representational Painting (1971), Anna Mendiata’s Body Tracks (1982) and Janine Antoni’s Loving Care (1992) would seem tailor-made for Darling’s subject. But this is really the fun of reading such essays: responding to and arguing with them, and generally getting the intellectual juices flowing.

Both catalogs would have been more useful with indices, and the Seattle catalog suffers from a particularly silly design decision to limit captions to alternate double-page spreads, so the reader must flip back and forth to identify the images, and to no obvious benefit. But both contribute to evergreen subjects and make for enlightening and entertaining reading.