I was in Miami last week for the rare trip not instigated by art, but it included a good bit of art nonetheless. I was visiting a sick friend, so had a chance to do a lot of reading. On the plane I looked at the current issue of Gastronomica, the sexiest, best-designed scholarly journal I’ve ever seen, with fascinating articles written for real people as well as food scholars; everyone’s interested in food, no? One article featured a sugar sculpture competition arranged by the Food Network. Food art has a respectable place in art history, since in the 16th and 17th centuries major artists provided designs for cakes as well as the elaborate decorations for special civic and royal events, not to mention 20th and 21st century artists’ edibles, such as the cake which graced the cover of the February, 2011 Art News, or Philadelphian Amy Stevens’ photographic series of confections. I’d been told about the magazine by an artist I like and respect, Julie Green, whose project, The Last Supper, is illustrated in the Spring, 2011 issue. It’s a grim and very effective meditation on capital punishment.

In 1999 Green began painting the final meal requests of death row prisoners, and she’s now done more than 400.

Green’s illustrations of the meals are painted in blue on white plates, making them a gruesome version of homely, blue-plate specials. She’s exhibited them across the country, and more information can be found on her website. The series, unfortunately, shows no sign of ending; Green says she’ll continue until capital punishment is abolished.

Patricia Hills Painting Harlem Modern; The Art of Jacob Lawrence (University of California Press, 2009) ISBN 978-0-520-25241-7

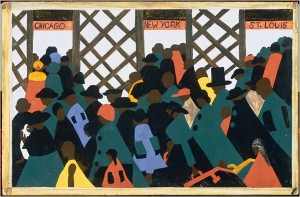

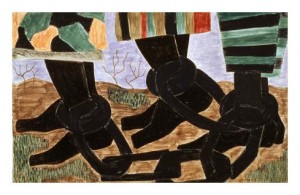

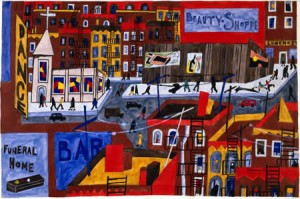

I spent several days reading Patricia Hills’ fascinating monograph on Jacob Lawrence. I’ve always thought that Lawrence’s 60-panel The Migration of the Negro (12 x 18″ panels) is one of the major achievements of mid-century American art. The fact that it doesn’t figure in standard art histories is probably because it stands outside the monumental, abstract works that are thought to represent American art at its high point. Lawrence’s abstracted, modernist figuration (which Hills terms his collage cubist style) overlaps with that of several other artists of more or less the same period whose work is also undervalued, among them Ben Shahn, Milton Avery, Alice Neel, Rufino Tamayo, and the slightly younger R.B. Kitaj. All of them acknowledged modernism’s rejection of academic techniques of illusionism, but refused to abandon figuration in order to include specific subject matter. Their work was figurative, but hardly realist.

Hills’ carefully-researched book is the product of several decades’ research and even the extensive footnotes make for good reading. She places Lawrence within an artistic community of writers, painters, and sculptors in Harlem during the 1930s-1960s and the small world of contemporary art in New York in the 1940s-50s. In doing so she creates a vivid picture of what it meant to be a Black man at the time, including racist incidents during his work in the Civilian Conservation Core; discovery of African-American history, not taught in schools, through extensive reading in Arthur Schomburg’s collection at the N.Y. Public Library’s 135th St. branch; trips through the Jim Crow South; ongoing support from teachers and others on the far left, many of them Communist Party members; and service in a segregated Coast Guard during World War II.

Lawrence had an extraordinarily charmed life as a young artist, attracting the attention of senior artists who supported his career, receiving ongoing funding from the Harmon Foundation and the Rosenwald Fund, early acceptance by one of New York’s most important galleries which immediately placed his 60-part Migration Series in two major museum collections, and support from his Coast Guard superiors who saw to it that he was assigned work as a painter. His professional success created somewhat of a barrier between him and other Harlem artists during the 1960s; it was not until his fifties that Lawrence needed a full-time day job to support his artwork (which lead to his move to Seattle).

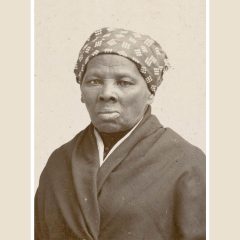

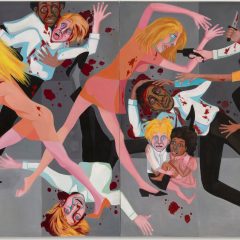

The book emphasizes specific bodies of work, notably three multi-part narrative series (on Toussaint L’Ouverture, Harriet Tubman, and the Migration of the Negro), scenes of Harlem, and work done during the civil rights struggles of the late 1950s and 60s. Hills discusses the work in light of African-American traditions of storytelling, the erasure of African-Americans within national histories, slave narratives, the writing of Richard Wright, Langston Hughes and others, photographic records of African-Americans, double consciousness (as theorized by Du Bois and Gates) and strategies of masking, and the political and social history of the period that included the Great Depression, World War II, McCarthyism, the civil rights struggles and the pervasiveness of racism.

The book is the most thorough analysis available of Lawrences’ work and a valuable contribution to American art history as well as African-American studies. It is very fully-illustrated with many color plates, and unusually attractively designed for a university press book.

Whale and Star, housed in an industrial building in Miami, contains the studio of artist, Enrique Martinez Celaya and the Whale and Star Press, which publishes books on art and poetry. It also serves as a space for a variety of educational events and public programs that Martinez Chelaya organizes (note: Michael Taylor will be speaking on Arshile Gorky on May 18). I attended a lecture by Suzanne Hudson, professor of art history at University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, president of the Society of Contemporary Art Historians and author of the recent monograph, Robert Ryman; Used Paint. She explained that her talk, Agnes Martin “On a Clear Day,” was part of a larger project about abstraction and spirituality during the 1960s.

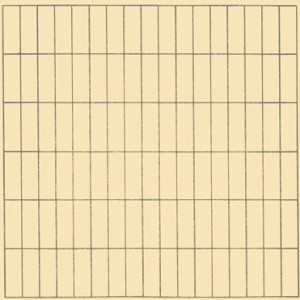

‘On A Clear Day’ was a series of 30 prints that marked Martin’s return to artwork after a 7-year hiatus. The artist never explained why she left New York (where she had established a serious career) and moved to New Mexico, nor why she stopped painting. Martin always disavowed mysticism in her work as well as any references to nature, despite giving her abstract works titles such as Starlight, Mountain, and The Desert. Hudson’s project emphasized historicizing Martin’s work and her public statements.

Hudson discussed the impact of Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring (1962) on the understanding of nature; the pioneering work of ecological warning revealed nature as a poisoned environment. Hudson suggested that Martin’s living close to Los Alamos and the original test sites for nuclear weapons would have inevitably made her sensitive to Carson’s message. Martin read widely so was likely to be aware of current thinking across many fields. Hudson also discussed the writings of psychologist, Abraham Maslow, whose ideas about self-actualization were taken up by some of the more outlandish 60s movements. In Maslow’s thinking, however, self-actualization lead towards a morality of the common good.

Hudson’s ideas were considerably subtler that these brief comments can convey, and I’m very much looking forward to the book that comes out of this research.