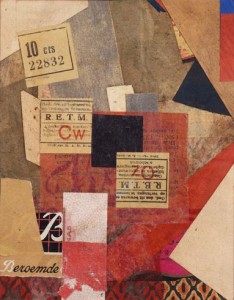

Kurt Schwitters: Color and Collage at the Princeton Art Museum through June 26, 2011 realizes the alchemists’ dream of turning dross into gold – in that Schwitters created his marvelous collages and assemblages from recycled garbage. This first U.S. survey of the artist’s work in twenty-five years does not attempt to cover his entire production; the roughly 80 works include several of the Merz assemblage paintings, a large number of exquisite Merz drawings (collages on paper), several small sculptural works and a reconstruction from photographs of the Hannover Merzbau, which was destroyed in WWII. While much of the work is from the 20s and 30s, it also includes a selection of work the artist did in exile in Norway and England. Organized by The Menil Collection, the exhibition at Princeton includes books and archival material from the university’s libraries and an audio of the artist performing his Ursonate (Sonata of Primordial Sounds) (1922–32), a phonetic sound poem in four parts that is essential listening. If you don’t get to Princeton, Schwitters’ performance, score and interpretations by several other performers can be found on Ubuweb .

Alfred Barr described Schwitters’ work as endowed with the unreasonableness of dreams, but to 21st-century eyes he was the ultimate poet of the broken, cast-off, fragmentary and disposable stuff of modern life. An abbreviated selection of his ‘palette’ includes bits of used metal (drain covers, small appliance parts), wood, newsprint, corrugated cardboard, wallpaper, tickets of all kinds, hair, lace, fabrics and cotton balls. He exploited their characteristic textures (exposing the cardboard’s corrugations, the roughness of burlap, the transparency of cheesecloth, lace and mesh screening) and construction: he often employed the selvage of fabric and delighted in the perforated edges of tickets and notebook pages.

A significant number of the works on view still retain the artist’s crudely-constructed frames, which are now surrounded by elegant and protective outer frames and often further protected by glass. Seeing them this way reminds us that Schwitters’ assemblages and collages of re-purposed trash, tastefully hung on the walls of the art museum, are rather like undomesticated animals in a zoo; this is not their native habitat. Schwitters worked in the nexus of several early 20th-century art movements; he combined the fractured forms of Cubism, Expressionism’s paint handling, Constructivism’s formal structure (particularly Lissitzky’s use of the diagonal) and the absurd juxtapositions of Dada.

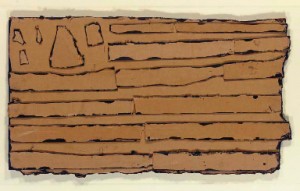

Just as important are the artists he influenced, and one of the happy features of Princeton’s hanging is that beyond the exhibition’s final gallery is another, devoted to post WWII American art. Immediately to the right is Claes Oldenburg’s Truck/Pants (1960), of corrugated cardboard with edges looking as if they were burnt (I couldn’t get an illustration, but his Big Cardboard Flag, of the same year, is below); to the left hangs a small Robert Rauschenberg combine from 1957 which includes a shirt cuff (with button), fabric selvage and a bit of a printed comic strip at the bottom. These are Schwitters’ progeny.

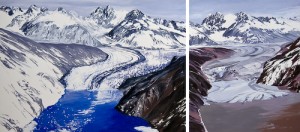

Of Art and Public Policy: Diane Burko’s ‘Politics of Snow’ at the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs, Princeton University

Diane Burko is interested in landscape on a topographic scale; theyare as far as one can get from Durer’s Clump of Grass. She’s been increasingly attracted to nature at its most extreme: volcanoes and now glaciers. Her exhibition Politics of Snow, new work in a series first exhibited last winter at Locks Gallery, Philadelphia is on view through May 19, 2011 at the Bernstein Gallery, Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs, Princeton University The gallery specializes in art whose subjects relate to public policy; it’s an ideal venue for Burko’s current series, in which she pictures global warming through contrasting images made from photographs documenting international glaciers over periods of time. The large diptychs and polyptychs, which often reach from floor to ceiling, tell a suitably heroic tale of mountain ice, the landscapes it created, and the tragic changes those landscapes reveal. The paintings are monumental, seductive in paint-handling and subject matter, and ultimately grim in the stories they tell.

The exhibition was opened on April 21 with a panel discussion; joining Burko were Adam Maloof, professor of geology at Princeton University and Michael Oppenheimer, professor of geoscience at the Woodrow Wilson School. The artist gave a history of her interests leading up to the glaciers and the question she faced of how to make art out of the topic of glacial melting. She found her visual sources through extensive research and contact with scientists, most of whom were extremely supportive. Geologists made photographic records available and Burko used them to bring her concerns and the scientists’ data to audiences well beyond the scientific and environmental communities. Maloof, a lively teacher who looked as though he might be more at home outdoors than in an Ivy League classroom (he wore extravagant, red suspenders with his cargo pants) explained that ice sheets are some of the most important records of climate, recording changes over geological time, in which 20,000 years is but an interval. Oppenheimer warned that we don’t have tools to indicate the rate at which ice is melting and whether the situation is merely grave, or catastrophic. Situating himself among the optimists in his field (how else could he continue?), he was obviously burdened by the necessity of making the scientific argument clear to a lay public and political decision-makers.

Art as Banking: Time/Bank at Portikus

I just heard about an interesting, interactive project: from May 7- June 26, Frankfurt’s Portikus will be operating Time/Bank, a project initiated by artists Julieta Aranda and Anton Vidokle in 2009, described as a platform that enables people to trade goods and services without using money. Time/Bank aims to create an immaterial currency and a parallel micro-economy for the cultural community.

Time/Bank at Portikus will include an exhibition of artist-designed prototypes for a time-based currency; a mint that will print and circulate Hour Notes (designed by Lawrence Weiner); an archive of notgeld notes—the alternative currency popular in Germany during the hyperinflation of the 1920s; a branch of Time/Store offering a range of items including artist’s editions and books; and a series of seminars and talks. Portikus will also be publishing a book in connection with Time/Bank.

There’s a link for opening a bank account, as well as job listings at the bank. I assume those are all in Frankfurt; there’s no indication that they’ll be outsourcing work.