Given the importance of music in our everyday life and our cultural obsession with musicians, we tend to know little about the often exquisite tools of music making. Two recent experiences shed light on the overlooked history and craft methods of America’s quintessential instrument, the guitar— a trip to the C.F. Martin Guitar Factory, and to the Met’s current exhibition “Guitar Heroes”.

My trip, or shall I say pilgrimage, to the Martin Guitar Factory was greatly influenced by my company—two local Philly musicians and lifelong guitar fanatics, whose excitement mounted as we got closer to our mecca: the appropriately biblical, Nazareth, PA. While the original factory still stands, tours are now lead in the snazzy new facility about a mile away, a site that attracts visitors from far and wide to toss around these prized instruments and watch them take form piece by piece. The tour began in the buzzing and whirring artisan chambers, with receding vistas of hanging guitar bodies, rows of gleaming polished necks, the graceful curves of custom jigs and the chatting and laughter of the artisans (who would occasionally flip over whatever they were toiling with and strum a little tune) and their Johnny Cash and Dylan-adorned work stations. Unlike in other factory situations, these workers seemed not only happy, but obsessed with their work.

While the tour appropriately focused on the history of C.F. Martin—a German emigrant who first started his business New York in 1833, bartering his earliest products for cases of wine, and later resettling in Pennsylvania in 1839—it also illuminated more general details about the history of guitar making in the US. Many early American guitar builders were of German descent, and lutherie, the craft of building of string instruments, was actually an outcropping of the cabinet building industry.

In Europe, back in the days when guilds ruled most creative enterprise, the Violin Maker’s Guild — seeking to limit competition — banned members of other guilds (such as the Cabinet Maker’s Guild) from producing musical instruments, an argument rooted in the distinction between the art of instrument building and the mere mechanics of furniture building. This tension caused many instrument builders to disperse, most notably to Italy where well-crafted instruments were in high demand, but also as far as America.

C.F. Martin, son of cabinetmaker and the supposed “inventor of guitars” Georg Martin, emigrated after too much frustration trying to deal with testy guild restrictions. The tour included tales from this early history, but also highlighted modern innovations: a line of guitars built from sustainably harvested and scrap woods, for instance, as well as mesmerizing robotic polishers. But beyond the mechanization of some preliminary and final steps in the building process, the methods at Martin remain remarkably similar to those used in C.F.’s days. The guitars, which are mostly acoustic, are still predominantly hand-built, requiring over 300 steps and six months to produce. Martin’s 600+ workers (referred to at the factory as “artisans”) are taught the entirety of the building process before specializing in one particular step. Consumers, which include famous musicians and discerning amateurs alike, still value Martin’s classically designed 6 and 12-string guitars (and ukuleles), finding in their traditional build the possibility for new sound.

While the Martin Factory, which produced its millionth guitar in 2004, gives a view into a more standardized, mass-produced (albeit handmade) product, the Met’s “Guitar Heroes” sheds light on the work of three 20th century craftsmen renowned for their highly personal, artistic designs and innovations: John D’Angelico (1905-1964), James D’Aquisto (1935-95) and John Monteleone (born 1947). These three Italian American artisans worked in and around New York to craft acoustic and electric jazz beauties of particular aesthetic and sonic originality—sought after by musicians such as Paul Simon and Chet Adkins.

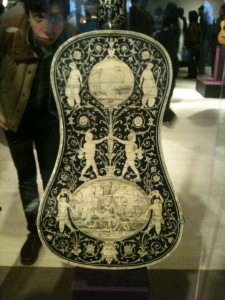

The show situated these three makers in a context specific to Italian instrument producers, and began with a description of the 1562 Guild of Luthiers in Bavaria and their eventual takeover of the Italian instrument industry. Among several outstanding examples of painfully intricate early instruments adorned with inlaid pearl and tortoiseshell was the austere guitar of famous violinmaker Antonio Stradivari—one of only four known ever to have been made.

While this show lacked the hands-on, mechanical component of a visit to a live-production factory, its attention to historical detail made clear the relationship between the innovation in instrument, and in music itself. Both the Martin Factory and the Met show hammered home that behind every skilled musical artist is a skilled craftsperson, or let’s just say artist: the person who wrought the perfect tool to create the perfect music.

To round out this experience in guitar history and craft, visit MoMA’s exhibition of Picasso’s guitar-inspired paintings, collages and sculptures—sure to add another level of insight into the impact that these beautiful handmade creations have had on musicians and non-musicians alike.

Tours are conducted Monday-Friday at the Martin Guitar Factory, Nazareth, PA

“Guitar Heroes: Legendary Craftsmen From Italy to New York”, at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, through July 4

“Picasso: Guitars 1912–1914”, at the Museum of Modern Art, through June 6