The first distinction that Tomi Ungerer made when I met with him was, “I am not an illustrator.” Then he clarified, “Well, sometimes I am an illustrator.” He prefers the French term Dessinateur which translates roughly to Draw-er, or a person who uses drawing as his or her fundamental medium. Tomi Ungerer, who is 80 years old, still understands and explains the world through making drawings, and I was given the opportunity to sit with him and talk about his creative process.

I asked if he would draw with me, and he shook his head in a way that suggested absolutely no. He seemed exhausted in a way that suggested too much socializing with people he didn’t know. “Anyway, you might think you’re seeing 2 or 3 madmen [in my studio]. I might be drawing a thing and suddenly I’ll have an idea, so ill go back and write a few things, suddenly I’ll go back over and work on sculpture… it’s completely scattered. I have so many interests and I have too many ideas.”

What I like about Tomi Ungerer is that his work is accessible and playful, and I wasn’t surprised to see this sort of creative exuberance come out of this man. He mentioned the importance of being interested and observant; “first develop your curiosity” and once that happens, “there is no end… The more curious you are, and the more knowledge and facts that you accumulate. Once you have all those facts, the real trick is to compare.” One uses his/her imagination to bring together two disparate things, and that is where ideas come from. I was reminded of a line from Narcissus and Goldmund by Herman Hesse: Der anfang aller kunst ist die liebe or “the beginning of all art is love.”

One example of his playfulness is the Katzenkindergarten—a cat-shaped kindergarten— he designed in 2002 with Turkish architect Ayla Yöndel in Wolfartsweier, Germany (right over the border from Strasbourg). You can look out the eyes on the second floor and slide down the tail. “Why not?” Is one of his mantras, along with, “I’ve got to have my fun.”

Ungerer is a self-described bibliophile; “I couldn’t conceive of a life without books.” He never finished high school, seemingly because education was not a priority in Alsace in the mid 1940s. Books were the things that enabled him to educate himself. “We were a condemned generation,” he told me. He later said, “I write the kinds of books I would have liked to read as a child.” Perhaps his ideal audience is himself as a child, and he hopes to comfort that young person through humor and showing how outcasts (e.g., a snake, an octopus, a winged kangaroo) can find happiness and meaning. Existentialism reaches even into his children’s books, not just overtly, like in his adaptation of Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain (Warteraum: Wiedersehen mit dem Zauberberg or “Waiting Room: Goodbye to the Magic Mountain,” Diogenes, 1985).

I asked him his opinion of University and upper education, and he acknowledged it as being a noble undertaking, but seemed suspicious of art school education, “you’re so marked by your teachers’ opinions, it’s going to take you 10, 15, 20 years to find your own style.” He practiced drawing constantly, “so that whenever I do have to illustrate a book or anything, I can really let my hand go.” And having a notebook on you at all times helps. I asked him how he manages to get anything finished when his interests are so varied and he responded, “Once I sit down [to write a book], then it’s only that… I have to eliminate everything else around me… because otherwise I’ll never finish.” Then he works 8-10 hour days.

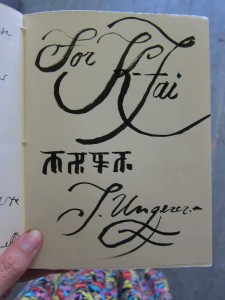

He saw the brush pen I carry with me and asked if he could do something in my sketchbook with it. He was quiet for the first time in the interview as he moved the brush along. “With calligraphy, writing becomes a sensuous experience. You have much greater contact with the paper than you would normally have because you have to make the motions “in one swing.” “Voila,” he said as he handed it back to me.

Tomi Ungerer’s attitude towards making things was very improvisational, and reminded me of a musician I had worked for in the past. When I suggested this, he leaned closer and confessed, “I actually came to American because of my love of jazz and the blues.” Some of his favorite musicians are Earl Scruggs and Lester Flat (the famous bluegrass players) “white trash music,” he said with a wide smile, “is what it was called in New York.”

One thing he did want to clarify was the use of the word “pornographic” to describe some of his drawings. “I draw erotic satire and I draw erotic work. I personally don’t find pornography erotic.” With that comment he highlighted a major cultural difference between his own mixed cultural sense and ours—America’s–limited scope of popular sexuality. It made me realize that Americans don’t have a spectrum of eroticism, it is either an on or an off switch; Pornography consists of the ugly, unfashionable men and women who perform for millions. “I fought for sexual liberation. My work doesn’t’ fit in with [pornography].”

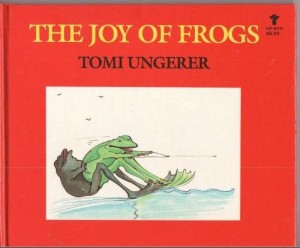

He published Das Kamasutra der Frosche (The Kamasutra of the Frogs) in 1982 where he drew and watercolored, “every possible position but it’s done with frogs.” Apparently numerous adults later approached him and said, “I was 13 or 14 and I saved up all my money to buy your book of frogs.” Perhaps its success was due to its well-executed satire – a more grown-up version of the birds and the bees. Or due to the fact that this was a self-aware book in a sea of how-tos during the Sexual Revolution.

Tomi Ungerer expressed relief in the middle of our conversation, “I’m so happy you’re coming with something specific instead of jumping from one thing to the other. Really what you’re interested in is the creative process.” Ungerer has somehow managed to maintain his creative endurance, not allowing his good work to have to be dug up, as poet Stanley Kunitz once said, “under the debris of life”. And with not many years left statistically, he is pushing hard to create as much as possible.

Buy his reissued books on Phaidon’s website. Also they have a fantastic clip of him discussing one of his books, Far Out Isn’t Far Enough here.