I love Amsterdam and have been visiting a close friend there regularly since 1998, but if you’ve never been to the city, this is not a good time to go. Much of the city is torn up because of large construction projects: at the train station (whose entrance is entirely obscured behind hoardings, below, and interior is also undergoing work); on major streets, where they are building a subway; and at both the Rijksmuseum and Stedelijk Museum. Both museums have a small selection of their collections on view, which is probably sufficient for tourists, but not for readers of artblog. The work has been ongoing for years and shows no sign of an end. It reminds me of the endless work on Lake Shore Drive in Chicago, which is obviously a works project for friends and family of well-placed politicians.

On arriving, I rented a bike and took a ferry to Amsterdam North with my friend Barbara Krulik, who says the neighborhood is otherwise known as Brooklyn, because it has cheap real estate where artists can afford work space. We went to attend the opening of drawings by Beldan Sezen, a Turkish German who lives in Amsterdam. It was held in a raw industrial space which is the new home of Dansmakers, an incubator of choreography and collaborative work where Barbara is managing director and Sezen records activities as a videographer.

Suspended above eye level were 80 poster-sized prints from, Zakkum, billed as a graphic murder mystery. It’s to be published in chapbook format later this summer by Treehouse Press. The story concerns family, loyalty and love, cultural etiquette and taboos, and social conventions about gender; although fictional, it was inspired by the death of Sezen’s aunt. The drawings had been shown in the Womens’ Museum, Wiesbaden in 2009.

The artist is a self-taught draughtsman whose work, by her own account, grows out of anger, humor and curiosity; much certainly stems from her outsider status as a gay woman of Turkish background, born in the small town of Weisbaden. Zakkum, however, is a universal story about excavating family secrets; the only particularity that ties it to a place is the fact that the Turkish language has no gender, which leads to confusion central to the plot.

Sezen is sophisticated about visual story-telling and employs various conventions of comics and film to tell her story, such as changes of focus, jump cuts, and first-person narrative where the protagonist’s internal life parallels the larger story. Her details tellingly set the story variously in Amsterdam, Vienna and Istanbul and while her characters are informally – drawn, each is well developed, with individual characteristics. This may be her first graphic novel (her previous work was in shorter formats), but she has mastered the form.

After the opening Barbara and I went around the building to the half which faces the water, looking out at Centraal Station, the new library (which I wrote about on July 26, 2009) and the city beyond; it has recently been occupied by Stork (below), a fish restaurant like nothing else in Amsterdam. It’s very large, whereas center city spaces are small; it has stylish, casual décor, and much of the wall facing the water is glass, with out-door seating beyond. We had a wonderful dinner which included the seasonal specialty of plump, white asparagus served with boiled potatoes and fish. The place was busy with a crowd that Barbara assured me was not from North Amsterdam, but had also taken the ferry especially for dinner.

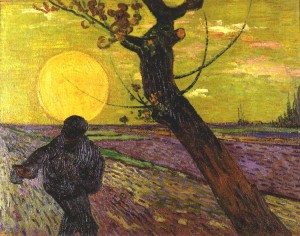

The Van Gogh Museum was fortunately open for business as usual, even though it was between special exhibitions. A group of Symbolist paintings from the permanent collection were on view, and a number of them were in the simple, white frames that many artists of the period used, since they usually had to pay for the frames in order to exhibit their work (they may also have chosen white frames as another way of distinguishing them from the gold frames required by the official, academic exhibitions).

It is always interesting to see Van Gogh’s copies of work by other artists (several examples after Millet) and be reminded that this aspect of academic practice was continued by the avant-garde (as was seen in the Philadelphia Museum of Art’s Cezanne and Beyond, ).