In 1968 the children’s book illustrator and author Tomi Ungerer donated over 4,500 of his drawings and book dummies to the Free Library of Philadelphia. It’s taken over forty years for those items to be properly catalogued and made available to the outside world. He is appearing at the Free Library’s Montgomery Auditorium (1901 Vine Street) on Tuesday, June 14th at 7:30PM to celebrate this and to be interviewed by Tony Auth.

Ungerer, who turns 80 this year, is part of the of post-1950s movement of supremely innovative and creative authors and illustrators who wrote for children. Amongst his contemporaries are Maurice Sendak, Roald Dahl, Quentin Blake, Edward Gorey, Shel Silverstein and William Steig to name a few. Ungerer is also famous for his political and advertising posters, and for his drawings containing mild to overt pornographic content. I spoke with the Special Collections Archivist Adrienne Pruitt to look at some pieces from the collection, and to perhaps figure out why children and adults are consistently drawn to the books and drawings of a man who has said, “My god, children are little bastards who chew and eat you up as they grow. They start with the kneecaps, maybe, and slowly they devour you.”

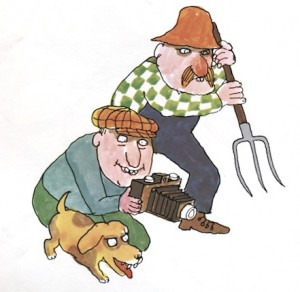

“Here are some manuscripts that were never published,” said Pruitt as she opened a large grey archival box, full of smaller boxes with drawings carefully nestled inside. Many of the drawings are done in pen and ink and watercolor, and the humor and spontaneity of both line and content is reminiscent of Saul Steinberg and George Grosz. A number of the drawings are doodles on scraps of paper with torn edges, apparently part of an effort to have made them smaller (“recently,” she emphasized with a frown – meaning sometime between the late 1960s and 2008).

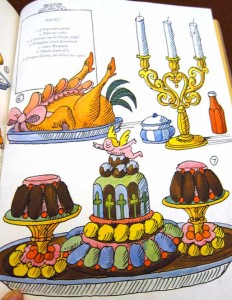

The collection spans the years 1955-1968. The manuscript she showed me was the original concept for the Mellops series: a family of pigs are tricked by another pig into being led to the slaughterhouse (the manuscript is in German, and the Pigs trot from a Rolls Royce towards an ominous red brick warehouse labeled Schlachthof). According to Ungerer’s handwriting on the outside of the manuscript, this pig story was one of the things he brought with him to the U.S. in his infamous “trunk full of drawings and manuscripts” when he moved to New York in 1956.

Ursula Nordstrom was the Editor-In-Chief of Juvenile Books at Harper & Row from 1940 to 1973, and she published much of Ungerer’s work. She used the phrase “good books for bad children” to contrast these edgy, challenging books with “more conventional sorts of children’s books that sentimentalized childhood” (quotation from Dear Genius: the Letters of Ursula Nordstrom). Ungerer was one of the steeds in her corral, amongst Margaret Wise Brown, E.B. White, Maurice Sendak, and Shel Silverstein. To put it simply, Nordstrom was responsible for the existence of Charlotte’s Web, Goodnight Moon, The Runaway Bunny, Harriet the Spy, and The Giving Tree. She also published Where the Wild Things Are in 1963 after it had been rejected by other publishing houses. Ungerer and Sendak are long-time friends; Ungerer dedicated Monsieur Racine (1971) to him. Ungerer also introduced Shel Silverstein to Nordstrom in 1957, “I never planned to write or draw for kids. It was Tomi Ungerer, a friend of mine, who insisted—practically dragged me, kicking and screaming, into Ursula Nordstrom’s office. And she convinced me that Tomi was right; I could do children’s books.” (Publisher’s Weekly, Feb 24, 1985 issue).

When asked about who he has in mind when writing, Ungerer has said, “I do my books for myself, for the child inside me. In that respect, they are selfish. They are also subversive. They see hypocrisy, and they know the truth of just about everything by instinct” (Through the Looking Glass by Selma G. Lane). The result is a book with no condescension; books with drawings that can be enjoyed by adults and children alike.

It seems as though Ungerer was writing for adults under the pretext of writing for children. It was a way for him to access a lucrative market (books sell more than magazine illustrations). Now that Phaidon has begun reprinting his books, a publicity surge has bubbled up around him and he is more prolific than ever, “I have about 12 books going; it’s madness,” he said in the most recent (June 9) issue of Publisher’s Weekly.

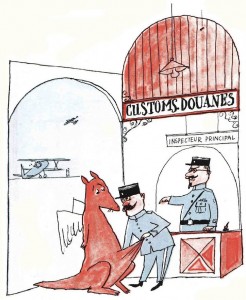

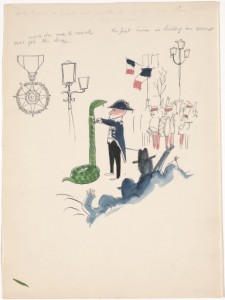

His stories are often formulaic; a typically “gross” protagonist with a good heart (a snake in Crictor, a Kangaroo in Adelaide, an octopus in Emile) shows heroism in a dangerous situation, protecting himself/herself and an innocent from intruders/dangerous types, and is ultimately rewarded with a statue in his/her likeness in the town square.

Nevertheless, his stories are creative and enjoyable, and they are, after all, picture books – the drawings take up more “page time” than the text. It is challenging to fit a complex plot into the 32-page standard layout, and still manage to have lots of engaging drawings. Perhaps that’s why he said, “I sometimes do 30 sketches—I never use an eraser, I just make another drawing—and yet even after all that it’s never perfect. I don’t feel that way about writing; I’m very pleased sometimes with the writing.”

And then there are his adult drawings, which you can see using a quick google image search or read a bit more about here and watch here, but I’ll save the reader the trouble and just post one rather inventive one:

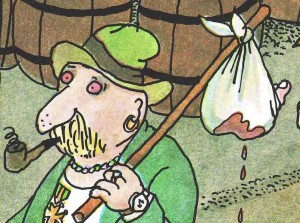

Nearly all of the adults drawn by him (both male and female) are being humiliated or about to face something unpleasant:

His best work, in my opinion, is comprised of the hidden details in the children’s book drawings. Like Brueghel or Bosch, Ungerer captures the unaware background characters and objects as they go about their hilariously disgusting lives. This is his satire at its best.

The Beast of Monsieur Racine (dedicated to Maurice Sendak) has a number of very good examples; a hobo carrying a bloody, dripping foot in his bindle. The possible explanation fished out by Selma G. Lanes in her book Through the Looking Glass: “A hobo does a lot of walking. He needs a spare foot for when one of his own gets tired and bruised.”

Another example from Moon Man shows the cruelty of a population to an outsider.

A friend of mine once quietly commented that “the best children’s books are really for adults.” I agree with him – partially. The best children’s books should delight people of all ages who want a guide to help them look at the world through a certain lens (and in this case, the same sort of lens Ursula Nordstrom encouraged). Tomi Ungerer understands that many children and adults understand and love dark humor. If it’s drawn the right way, a mysterious bloody box can be wildly amusing.