Mairead O’hEocha’s paintings are a stealth project. Her exhibition, via An Lár (An Lár is used on Irish road signs to indicate the town center), at Trinity College’s Douglas Hyde Gallery (through July 13, 2011), consists of purportedly deadpan views of contemporary Ireland. They’ve been accepted as such by critics and by the curator who wrote the introduction to the exhibition, which places O’hEocha in the tradition of Corot, Morandi, and Maureen Gallace (who does, indeed, paint deadpan Irish landscapes). These viewers have been taken in by the paintings’ craftsmanship, the subtlety of their restrained pallet, and the enduring popularity of landscape in Irish art and imagination.

Mairead O’hEocha embodies Harold Bloom’s concept of belatedness; he wrote about literature, but the same can be said of the visual arts, and most particularly about painting. What can a serious painter do after Manet, Picasso, Pollock? O’hEocha shares this predicament with several generations of painters following WWII, including Fontana, Lichtenstein, Yves Klein and John Baldessari. I suspect she also shares Theodore Adorno’s concern that after the horrors of the 20th Century, art cannot continue as usual. Her paintings parody the sublime, filled as they are with the lowliest of contemporary structures: box-like warehouses, garages, generic cottages and kitsch decoration intended to personalize the landscape with the degraded, mass-produced descendants of the Classical tradition.

These modest, easel-sized landscapes include everything that Irish Tourist Board images leave out: banal and littered urban and suburban spaces, mobile homes, abandoned property, bags of garbage and security cameras. And they avoid the well-developed conventions of landscape painting: a clear progression from fore to middle to background, a visible vanishing point, framing foliage and staffage (people and animals included in landscapes to liven them and aid the composition). Her brushwork becomes more lush and impastoed in areas where the paintings represent the least, reminding us that even within representational painting, such brushwork inevitably represents not the subject, but the artist.

The exhibition’s title directs us to a center which is always missing, for the paintings are particularly un-centered and without focus. The wall in Church St., Gorey, Wexford obscures what might be a view beyond, yet offers too little to hold our interest. Like Gertrude Stein’s famous description of Oakland, there is no there, there. One scans the abject sites for meaning and understanding which they never reveal. Some of the forms do not even resolve; what is the box-like object in front of what is presumably a mural on a courtyard wall in Workyard, Smithfield, Dublin? Or the formless, white shape on the far left of Enclosure, Unyoke, Wexford?

This provocative and disturbing body of work addresses more than the Celtic Tiger, now bankrupt and in debt. It speaks to that segment of Ireland whose national myths have not caught up with industrialization, much less the world wide web; whose artistic values are stuck in a time warp that occludes the present and hence, any workable vision of the future. It is a demand to see things as they are, as a necessary first step to improving them.

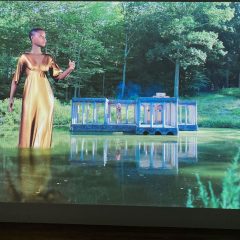

Second Burial at Le Blanc

Sarah Browne’s installation, Second Burial at Le Blanc at Project Arts Centre, Dublin, May 6 – June 25, 2011, is the artist’s version of an anthropological study of current European conventions of time, value, exchange and community, which she conducted in the small, French town of Le Blanc. As a bid for visitors and tourists, merchants and craftsmen in the town have chosen to continue doing business in francs rather than euros for the past nine years, until Feb. 17, 2012, the last moment they are legal. Browne explains that her work is both salvage ethnography (documentation of dying customs or rituals) and surrealist ethnography (attempting to make the everyday seem strange).

Browne created and distributed a bilingual, tabloid newspaper entitled On Hoarding, Accumulating, and Gifting to the residents of Le Blanc; the title is a slight variation on a phrase in Stone Age Economics by the anthropologist, Marshall Sahlin. Brown’s newspaper is a visual essay with short historical comments and citations from a variety of European political figures and scholars; these address topics the artist has woven into her project: the transition from franc to euro, its effects in terms of a common European economy, hoarding behavior, gifts, currency, and rituals such as military, burial and ticker tape parades.

Citizens of Le Blanc participated in a procession through the streets on April 1, 2011, carrying a ticker tape machine that records Euro exchange rates as it counts down to Feb. 17, 2012. The machine, Browne’s gift to Le Blanc’s residents as a memorial of the currency transition, is carried on the sort of simple litter used in religious and funerary processions. Browne also relates the procession to the custom in Madigascar in which the dead are dis-interred, re-shrouded, and carried to a second burial – hence the second burial of Browne’s title. Browne’s newspaper also relates the slow pace of parades by the French Foreign Legion to political history and to French colonialism; this leads to the question of whether the larger cultures of the European Union will colonize the minority cultures.

The installation consists of a back-projected, 10-minute, 16mm film of the burial procession; the ticker-tape machine, sitting under a glass bell jar on a pedestal and continuously extruding printed tape; and a stack of the newspaper On Hoarding… free for the taking. The film is in the traditional format of hand-held documentary; the only sound in the gallery is the regular clicking of the film projector and the less frequent sound of the ticker tape machine as it prints. These sounds, and the newspaper, emphasize the obsolescence of the technology (celluloid film, ticker-tape machines and possibly even printing) which the artist has used in her project exploring obsolete currency and the impact of change on a community.

Browne emphasizes that time and currency, like art, are man-made concepts which function only by communal agreement. Last Burial … addresses the impact of a broadened community brought about by adoption of a common currency. She questions the impact of this aggregate community on the rituals and customs of local communities: how much of Le Blanc’s particularity will survive becoming European? Can a continent-wide community find social rituals of cohesion to replace long-evolved local rituals? The European economy is already communal, with the very pressing result that France, and the citizens of Le Blanc, are now responsible for financial crises in both Greece and Ireland (Browne’s local community and also a minority presence within Europe). What sorts of social changes will accompany this economic interdependence? And at what cost?