I finished viewing Ryan Trecartin’s Any Ever and left bloated with images, memes, and satires. The exhibition, which runs at P.S.1 through September 3, is composed of seven independent but interrelated videos. Trecartin’s work relies heavily on references to reality television and leaves viewers rattled by the ever-blurry distinction between his video world and our own. Any Ever carries a lot of virtual hype, but invites you and your emotional reaction to roll around on a real world couch made of walkers and hospital mattresses.

Resist the temptation to simply watch Trecartin’s work online, despite how fitting that medium seems. The P.S.1 show captures the ride-like experience Christopher Knight portrayed in his column after he saw Any Ever at LA MoCA. You walk into the first room and the first of seven videos, each around forty minutes long, is already playing, though you don’t hear anything yet. Part of the Trecartin experience involves strapping yourself in — not with a seat belt but with large headphones tethered to the installation, which provide the audio for the video.

Delightful surprises await you in each room’s unique set-up. The room’s theatrical viewing arrangements range from the previously-mentioned walker-beds to futuristic conference rooms coated in sterile white to whimsical seating on ladders. Some of the installations include objects referenced in the videos, which either immediately tickle you or act like Chekhov’s gun, something you wonder about as you sit and watch, trying to figure out how the real world things factor into the videotaped action.

Once admitted into his post-race, post-gender, new media world, you see how Trecartin’s Disneyworld and Disney Channel influences start to melt together along with the milieu of media and culture he has encountered in various studio settings from Rhode Island to New Orleans, Philadelphia, Los Angeles, and Florida. The first four movies involve characters played by Trecartin and friends, who encounter career and safety pitfalls and a parade of schemers and dreamers. The characters’ smacking blood-red lips spew coherent-enough dribble in one disjointed scene after another so a semblance of narrative is conveyed. Although the narrative comes through also simply from the overused montage editing and mood music from bad movies and commercials.

Despite the absurdities in speech and costume and the break-neck speed of the editing and dialogue, these nonlinear movies make a frightening amount of sense for anyone who has watched enough melodramas or YouTube celebrity videos, or experienced, even second-hand, the reach of viral marketing.

I agree with Massimiliano Gioni , the director of special exhibitions for the New Museum, who applied critic James Woods’ term “hysterical realism” to Trecartin’s work when the artist showed at that museum. I further defend “hysterical realism” as not necessarily comparable to other contemporary art, but a form that nonetheless illuminates the modern condition. James Wood critiques “hysterical realism” as a literary genre whose elaborate absurdism fails to convey how a character feels but instead reproduces social theories on how the world works. Many viewers and art critics have welcomed Trecartin’s constructions of social reality. But an entire reality, encompassing the multitude of themes he employs, sometimes feels better suited for a novel. Trecartin’s videos honestly overstimulate and confuse you.

The blue-toothed and tan characters swim fluidly through multiple ages, races, nationalities, and genders. A young girl with a Visa card tattooed to her forehead encapsulates the underlying conceit for many of the films — market research. But, jump cuts to Telenuevas and music videos make no sense but fail to throw you for a loop. And the threat of violence from the destructive behavior becomes, finally, an aesthetic. With nothing to fear and no one to fear for, I nevertheless could not help but start to feel a bit afraid towards the end of how plugged in to this mediated world I must be in everyday life.

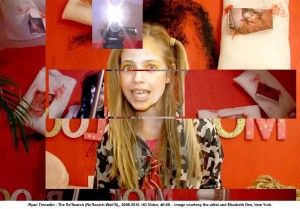

It took me less and less time in each room to suddenly sink into each world’s explosion of different themes. Two minutes into “Temp Stop,” I felt like I knew the character of a busy busy Blackberry boss-bitch dressed in black. One minute and without needing to put on headphones in the absurdly-constructed gym-machine room, I recognized the play on fitness culture and threw on headphones to enjoy the seemingly-pregnant instructor on film rhyming “stretch” and “vetch” with oomph. The last and least absurd room for me, “The Re’Search,” involves tween tweet-texting pop-stars gossiping viciously about each other and commenting on language in self-referential phrases, confessing their inability to spell or support “language diversity.”

Not surprisingly, Trecartin has noted that a target audience for his video art is this tween age group, which has never lived in a world without Internet and which communicates through new technology, while speaking an increasingly dissimilar language to our own. “The Re’Search’s” youthfully exuberant pace and language and “Temp Stop’s” eerily ordinary speeches haunt you as you walk away from Trecartin’s world not sure the ride you are on is over. It’s a small and histrionic world after all.