Savage Beauty, the Alexander McQueen exhibition at the Met is something of a curio cabinet from McQueen’s studio. Sam Gainsbury and Joseph Bennett, the production designers for McQueen’s fashion shows, served as the show’s creative director and production designer, bringing a dramatic and potentially-narrative structure to the exhibition, all the while echoing the theatrical aspects of McQueen’s work, his thinking and his collection presentations.

Lee Alexander McQueen was born in London in March of 1969. His death by suicide one week after his mother’s death in 2010 does not shed light on his work nor on his intellectual curiosity. But his death, and death in general, hangs over the show like a dark shadow. McQueen was fascinated with death–it was his subject, the way it was the subject of the Romantic poets with whom he’s been linked.

McQueen’s sources ranged from the Romantic authors and poets of the 19th century to the traditional shapes of Japan and the far east. The entire range of visual and literary history is reflected in the colors, shapes, lines and textures of his work.

He presented everything as a moment of revelation – an overwhelming revelation of shape, texture and weight. He called himself “a romantic schizophrenic,” and he seemed driven to explore the elements of his life and the world around him, always pointing a finger and pushing a boundary. He was continually reaching back to themes and looks from the past and always looking at death and mortality.

McQueen left school at 16 and immediately set about learning his craft. He apprenticed with traditional Savile Row tailors; worked with theatrical costumers; and later worked at Givenchy. All of these sources took root in his vision, and they all had an influence on the exquisite execution of his designs.

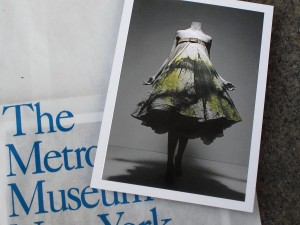

The exhibit includes over 100 garments, ensembles and accessories from McQueen’s career from 1992-2010 and is broken into about 10 different staging areas starting with his early postgraduate collection from 1992 and running more or less chronologically through the collections year by year. (See an 8-minute video gallery-walk-through with voiceover by Curator Andrew Bolton)

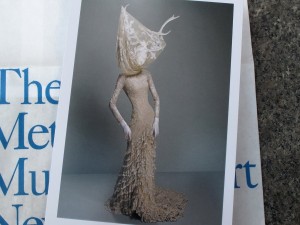

The gallery adjoining the student work features Romantic garments and some that DeSade would approve of, with dark fabric, leather, chains and feathers haunting the space and imagination. Here, as throughout the show, the mannequins’ heads are completely swathed or hooded, sometimes in leather, sometimes gauze. This weird masking or obliteration of the head and face sits heavily on the show–giving it an uneasy, fetishistic touch that I think the artist would like.

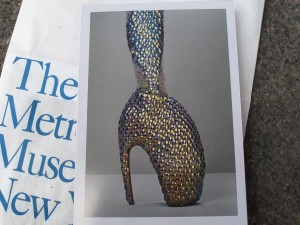

Next in the show’s labyrinthian and claustrophobic floor plan is a gallery that functions as something of a walk-in closet filled with all manner of fantastic and decorative accessories along with some apparel. Inset, high on the walls, amidst the headwear, shoes and jewelry are tv monitors playing clips from some of McQueen’s lavish runway presentations. The videos bring the ensembles to life–as they bring the crowd to a halt. While all the rooms in this exhibit feel congested due to the large crowds snaking slowly through, this room is wall-to-wall bodies staring at the videos and baubles, which are close enough to reach out and touch in some cases.

As for those videos (see them on the Met’s website), at times they feel more like scenes from a play or opera or contemporary performance art. Seeing the clothes moving through space on the fluid frames of the models humanizes the designs (it helps that the models, for the most part, don’t have to wear those strange head shrouds that the mannequins wear).

Robots or machines take part in the a couple of these video dramas adding to the theatricality. In one video, a model is attacked by two multi-jointed paint robots borrowed from a car painting factory. The model is seen revolving on a turntable on the stage; the robots spray her dress (and her) as she feigns fright but stays rooted to the spot. Voila, the dress is finished and she totters off, to great applause, performance over. In the exhibit, you can see the dress right under the video of its making.

The rooms that follow show McQueen expressing his ideas and feelings about culture, politics, and his Scottish identity (who knew tartan plaids could be so sexy).

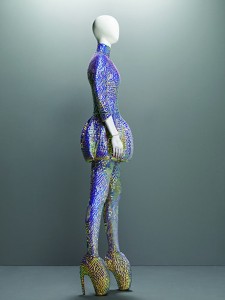

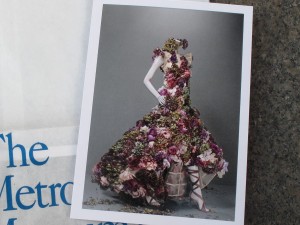

After about an hour of winding through these dramatic scenes with moody music — there is music throughout not just in the videos — I arrived at the final runway presentation, which was posthumously presented in February 2010. The garments, on mannequins with space-age coifs, look forward and back at the same time – to the ancient shapes of nature and art history as well as to the sci-fi and alien creatures of our future. McQueen the artist, whose true medium of expression was fashion.

Leaving the exhibition I visited the requisite “store.” In addition to t-shirts, a catalog and postcards, there is a tiny replica (a Christmas ornament) of McQueen’s signature “Armadillo” shoe ($25). There is also a small display of “influential movies” you can buy including Orlando, The Birds, Psycho, The Hunger, and They Shoot Horses Don’t They. An interesting collection of haunting narratives.

The Costume Institute at the Metropolitan Museum of art has “a tradition of celebrating designers who changed the course of history and culture by creating new possibilities.” Savage Beauty, organized by CI curator Andrew Bolton, continues that tradition. More at McQueen’s website and see more photos at the Met’s website.

Afterthoughts – Savage Beauty, not so savage line

I took a chance on seeing the McQueen exhibition on the 4th of July – a form of patriotism coupled with support of the arts. (I was also hoping the line would be less of a crush).

On entering the museum, I saw a sign announcing a 15 minute wait – I took that as a good sign and headed to the end of the line, prepared to wait.

What drew all these mid- summer patrons? The line gave no hint of what was ahead.

The Line

– 4 bodies across and 2 blocks long

– the crowd in my surround was primarily clad in flip-flops, shorts and pastel colored summer tops

– ages ranged from 10 to 60+

– language and ethnicity seemed like a line at the Tower of Babel (I would guess)

– the line refreshed itself several times over

The Time

– 15 minutes morphed into 30 as my fellow waiters and I inched along the parquet floor

– the corner teased us on

– suddenly, a rush through the final stop and ! WE were IN !

The Exhibition

– an overwhelmingly theatrical maze

– an overwhelming visual experience

– a small gift shop

After an hour in the exhibit, I wandered back in to the mundane halls of the real-time museum. I walked past the line which was now even longer than when I was a member. I made my way past hundreds of years of visual history, down the grand staircase, out the door and back to the throng of people and yellow cabs pouring down Fifth Avenue.