By Mary Murphy

This show at the Academy is notable for the way its title is embodied in the jostling relationships among the works displayed. Like city residents, they bump into each other in various contexts, defining the urban environment as a place of anonymous intimacy, dynamic energy, and jarring juxtaposition. Four local emerging artists use a variety of means – scale, color, gesture, and context – to state these themes, but each connects them differently toward social ends.

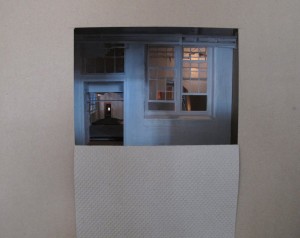

Amy Walsh’s installations initially seem part of a renovation; plastic sheeting attached to wooden studs signals a construction site. Realistic imagery silhouetted by lights strategically placed behind the plastic suggests intention, as do small, rectangular “peepholes” in the facades. These vantage points yield glimpses of miniature domestic and industrial interiors. Our feet remain fixed yet our eyes are constantly deciphering complicated recessional spaces through elaborate lighting effects. While the large exterior facades encourage an ambulatory, sculptural experience, the “peepholes” frame the interiors, suggesting two-dimensional illusionism. The scale shift from macro to micro locates our body as the mean between both extremes, making us more aware of our own physicality and curiosity. Walsh’s interiors become empty stages onto which we project our own narratives. Their tenuousness mirrors our fragility, our perpetual failures and reinventions.

Ben Peterson’s large, colorful paper and ink drawings also posit a micro/macrocosmic vision; but his views coexist on the same plane. These fully realized imaginative worlds contain a wealth of minute detail nearly exceeding our visual capacity. Large, welcome empty expanses surround a central scene, leading outward to white frames that soften the edges where reality and imagination meet.

These are seriously playful drawings, full of wit and gravitas in equal measure. The precision of the microscopic details creates an intensity that somehow feels liberating; freedom and playfulness come from its emphatic limitations. In these fantastic hybrid landscapes nature and culture collide, and nature is uprooted, displaced, and contained. Differences do coexist, uneasily; everything is stretched taut and about to snap. Yet out of this atmosphere of exquisite tension strange alliances are born: luggage creates a building facade; terraces become boats; sundeck chairs sit idly atop spindly scaffolding. Like nervous laughter in the face of tragedy, the climate bespeaks an unsettling dread: the moment of ripeness holds within it the beginnings of decay.

If Peterson’s drawings echo Walsh’s interiors, Arden Bendler Browning’s large flashe and acrylic gouache paintings on Tyvek suggest Peterson’s drawings on speed. Rather than tension and conflict one senses excitement, conveyed through a full repertoire of mark making. No longer spectators, we are now immersed in the city, like Degas’ flaneur. We see parts of things, not their entirety. But unlike Impressionism’s newly mobile urban pedestrians, we are in stasis; it is the city that swirls around us. This is urbanity as a kaleidoscopic abstraction. But this is not a “real” space. The abrupt changes of scale and direction, the deep yet inaccessible space, and the fully chromatic unnatural colors suggest a virtual reality rather than a real cityscape. We are, as in Renaissance perspective, static viewers once again, not because of the “eye of God” but rather the “vision” of the computer, which knows no hierarchy. In this digital language, various spaces exist simultaneously, their disjunctions part of a postmodern conceptual grammar.

We experience Browning’s forms physically in part because of their large scale, and because these paintings have no frame; they bleed out to the surrounding areas and envelop us. Browning leaves part of the surfaces bare; without frames, we connect these white areas to the wall, stabilizing the image and causing it to appear cut out, or shaped. Using Tyvek as a ground lessens the object-ness of the paintings, and increases their illusionism.

Browning’s palette and color usage are not far from Peterson’s; both employ flat, opaque shapes of chromatic intensity and more grayed out transitional areas, but Browning’s color is generally created through transparent layers. This gives her work a hazy affect and helps unify the paintings. The various shades of gray are each made differently and because chromatic grays are highly responsive to surrounding colors, their effect is multiplied. They act as foils for the stronger colors and create a palpable sense of urban smog. Browning’s titles (Up to Speed, Plenty of Eyes) acknowledge the city’s energy, scale, and variety as a source for her imagination.

Detail, The Dufala Brothers 20 Yard Dumpster Coffin, 2011, Dumpster, steel, plastic, insulation, PVC, wood, paint, buttons 21ft. x 8ft. x 4ft 8 in. Courtesy the artists and Fleisher/Ollman Gallery

Steven and Billy Dufala use found materials as vehicles for witty and incisive social commentary. Scale is a crucial aspect of their aesthetic; often, as here, they combine odd scale with altered context to create uncanny surrealistic objects. The strength of the Dufala Brothers is their light and humorous touch. Their objects are never didactic, but rich in allusion. Initial readings of their work are deceiving; under sometimes-banal surfaces, the content is consistently thoughtful and refreshing.

In 20 Yard Dumpster Coffin, 2011, the brothers use an object iconic of urban transformation, “upholstering” its interior with insulation-filled plastic pillows to resemble a coffin. The result is more than the sum of its parts: while the scale of the dumpster and the materials used are playful, the linking of similar forms that have disparate social contexts allows for a wide breadth of possible allusions, from homelessness and domesticity to mass graves and the communal rituals of private deaths.

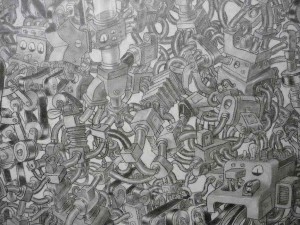

Heap, a large graphite wall drawing, contains a bracing social commentary. Stylized Leger-like machines proliferate with shaded linear belts that serve as connectors. Everything (read everyone) is connected; and while this might initially seem comforting, the corollary is that no one is autonomous; identity is collective. The title comes from the overall form of the drawing, a large pile of nearly replicated machines that almost reaches the ceiling; the individual shapes are only important in terms of the space they occupy. Their slight variations are deceiving. Attempting to decipher actual objects, it’s difficult to hold your place; they are physically dependent on each other and fundamentally alike, like siblings or villagers. The heap suggests that our value lies in our collectivity, and that we are expendable, like garbage; the form suggests a superfund site or a mass grave.

Disorder, randomness, and the unpredictability of (human) systems are literally spelled out in Entropy, another wall drawing, in which the title is made of electrical conduit and junction boxes. The scale of the letters is human-sized, yet readability is difficult because the conduit pipes have standard connector curves that don’t correspond to the degree of curved Alphabet letters. This slight hesitation in readability increases our visual interest as the piece slowly unfolds. The prominent junction boxes warn us that this sign is potentially lethally electric. A growing unease develops as we sense the metaphorical allusion to the death penalty. Entropy suggests our potential for anarchy, and our tenuous control over it.

This thoughtful and tightly conceived exhibition, curated by Julien Robson, PAFA Curator of Contemporary Art, challenges our understanding of urbanity by reanimating aspects of it, both positive and negative. Echoing and playing off of each other, these artists take the city as their muse, allowing their imagination to mingle with its energy. The results are both visually compelling and conceptually powerful. The show is up until Sept. 4.

Mary Murphy is a Philadelphia artist and educator.