by Julian Phillips

You will find the staircase to Robin’s Bookstore and Moonstone Arts Center between two bustling restaurants on an equally busy street. Once upstairs, you still might be able to hear the rabble and cries from those encamped at City Hall. Their chants and shouts are not intelligible, and many wonder what the protestors are trying to say. However confusing their message, we know why they have chosen to occupy the city center. We all feel it, hear and talk about why rabble-rousers and Americans hang their heads together. And the Class Warfare exhibit at Robin’s/Moonstone will show you.

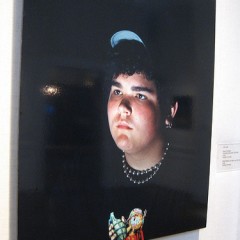

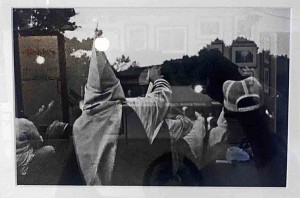

Class Warfare In Philadelphia is a five part educational series presented by the Moonstone Art Center. The photographs in the exhibit act as mirrors for gripping stories that exist but have been hidden by the media haze and politics of the recession. The truth behind the photographs is what is both gripping and frightening. The largest color print, by Justyna Badach, is titled “VEK”. The picture was taken the day the subject learned of his eviction. The image catches your attention when entering the bookstore. And you are stunned because the subject is so bewildered. He sits on a stool frozen with his belongings around him, disheveled and recently homeless. Your mind subconsciously might start to erase the belongings from the frame, considering how they will soon be gone, but you will never be able to rid yourself of the subject’s devastation.

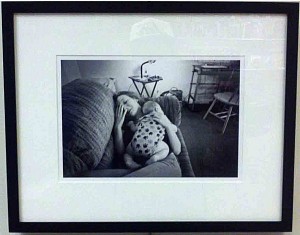

Most of the pictures follow in the same vein as glimpses into lives we may or may not share but understand and empathize with. One of the best examples is a photograph by Kevin Cook of a mother holding her child. As the mother cries she tries to conceal her sobs from the child on her chest by turning her head away. The child seems content, with her or his only wish to be with the mother. This black and white work communicates the history of photography’s role in documenting economic hard times. It is akin to the well-known Dorothea Lange photograph of the Migrant Mother. The same shroud of namelessness and grief are in both photographs. However, the mother in Cook’s picture cannot hide her emotion from the photographer – and maybe she shouldn’t.

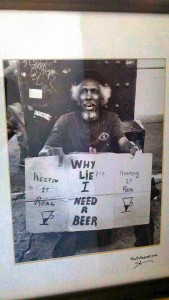

This recession is visibly different from the Great Depression of the 1930s, but the photographs of Class Warfare are eerily close. What adds to this feeling of historical continuity with the past — as you discover photographs in every nook and cranny of the bookstore — is the fact that the images of Class Warfare are mostly untitled. During the Depression, photographs by Lange and others appeared in magazines and newspapers showing us the pain the economic downturn. Now we get little magazine coverage, but photographers like those in Class Warfare continue to document. The idea of class warfare has been called unpatriotic, divisive, and false. But it is living and breathing in these photographs, which are as diverse as Philadelphia and our nation.

The photographs of Class Warfare allow for a discussion we need to have. Photographs do not shout, have a political party, or run for reelection. They show what we can all tell through a war that is not only between the rich and poor, but between the idea of America and the reality of American citizens’ lives.

The photographs of Class Warfare in Philadelphia are on view until November 3, coinciding with a panel discussion.