I was drawn to Sonya Clark’s show at Snyderman Gallery by a photo of a chair she had made–a found armchair festooned with braids that hung off the back and bottom like Spanish moss. Fit for an African king I thought.

Once I got to the gallery, the works that gripped me were the more personal and edgy–pieces made of real hair and an intimate drawing of her husband’s closely cropped head viewed from above, in which delicate, controlled ink marks repeat the growth pattern of the tiny stubble.

Clark’s central subject at Snyderman is African hair, and its social and financial implications in American society.

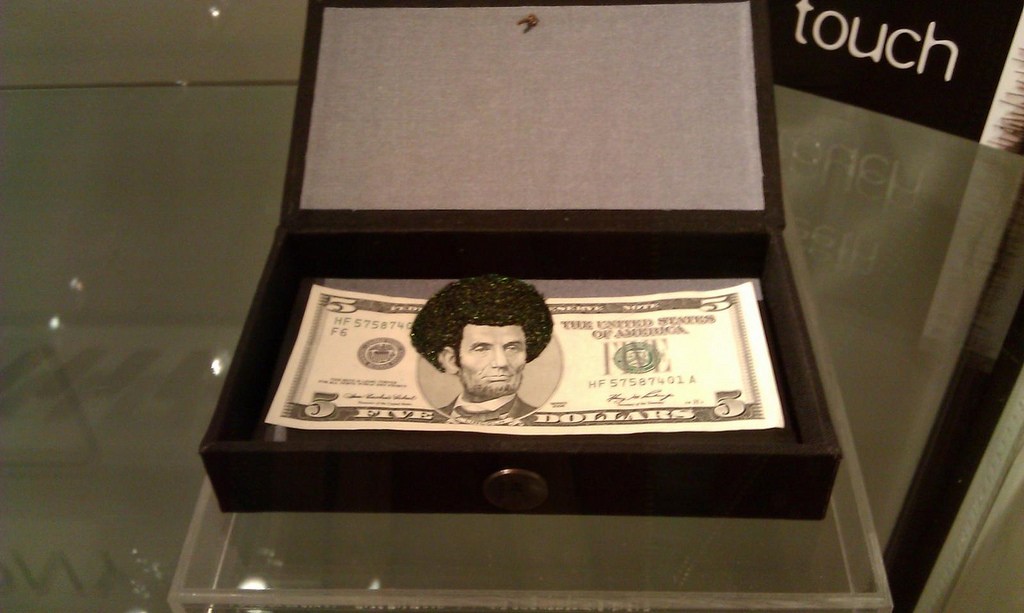

The small pieces made of real hair balled up to make pearls and abacus beads, and also stitched to give Abe Lincoln on five-dollar bills an afro, have some of the voodoo power of human excrescences. These pieces also create value and worth using that which society has historically scorned.

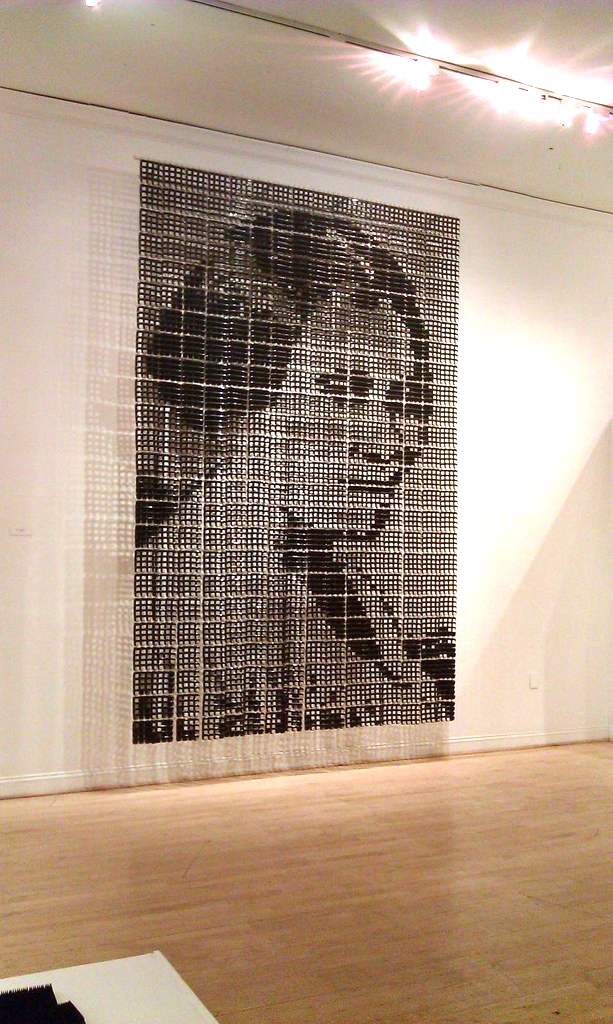

Issues of value also come up in an enormous portrait made of 3,000 small black combs. The scale reflects the subject, the enormous persona of Madam C.J. Walker, who started her life in slavery and ended up the richest self-made woman in America, perhaps the world, thanks to the hair products she made and sold to the African-American market.

Clark, who as been awarded numerous grants and awards, including a Pollock-Krasner grant and a Rockefeller residency, is chair of Virginia Commonwealth University’s Craft/Material Studies Department. Her MFA is from Cranbrook, her BFA from the Art Institute of Chicago.

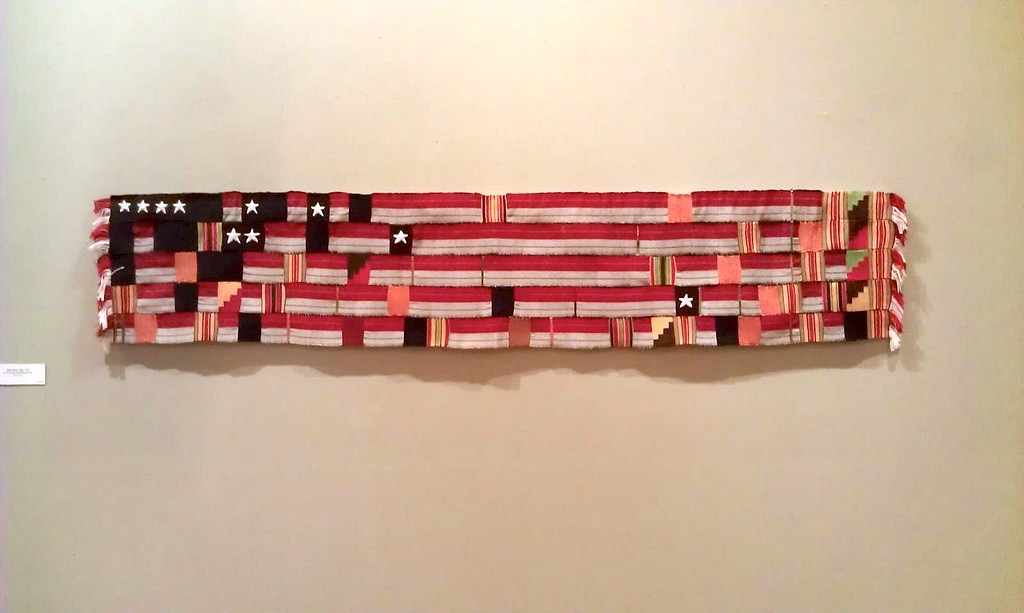

Hair is not Clark’s only subject. The 2008 show Taboo to Icon at the Ice Box in 2008 for instance included an array of stitched and beaded tiny talisman bags and charms. In this current show, there are also a pair of loafers and a kente-cloth-technique flag that hint at her wider practice and breadth of interests.

On the evening of Clark’s talk at the Philadelphia Art Alliance, she spent a couple of hours being gracious to all comers at Snyderman.

After visiting the work around the gallery, I asked Clark some questions about hair and race, and here are some of the things she said:

“When I traveled to Ghana I was identified as a white person, and I said, Whaaaat???”

She said she straightened her own hair until she was about 20. When she let that go, she saved $60 per hairdresser visit–and suddenly realized that the hairdresser had an investment in how Clark wore her hair. With her new natural do, she found that black women came up to her on the street, proud of the unstraightened style.

“This is when I realized my hair is not my own. Hair is collective. One strand has my whole DNA in it. My little girls [that’s what she called Malia and Sasha Obama] go to the same school I went to. When one of them wore cornrows to school, the cornrows got criticized as inappropriate–by white and black people. Hair is collective.”

In affirmation, I mentioned that Hillary Clinton also got criticized for her hairdo when Bill Clinton became president.

Then she started talking about how slavery had disrupted the knowledge base of how to care for African hair. The slaves worked so hard and had such long days, she said, that they didn’t have time to instill hair-care information in the next generation.

Clark mentioned that there is an assumption that if hair is unkempt and uncombed, it isn’t clean. Then she went off into a discussion of fine-tooth combs and head lice. She said straight hair is more susceptible to lice. Hair that is combed straight with a fine-tooth comb (like the kind used to remove head lice and nits) looks hygienic. And so the ideal of finely combed, straight hair was an example of an aesthetic thing coming from a hygienic thing. Her implication was that a white value was being transferred to people to whom it didn’t apply. (For more info on lice and hair types go to the University of Nebraska-Lincoln head lice FAQs and check out question #17. It’s full of juicy information!)

Then we talked about how everyone is of some mixed race, somewhere along the line. Clark herself has a white great grandfather, and is of Caribbean and Scottish descent. “If you have hair like me, and there are no black barbers in town, I will look for a Caribbean or an Arab or an Italian barbershop,” because many people in those groups have inherited African hair.

The show at Snyderman–the gallery’s first solo show of her work– comes down after Saturday (Nov. 19, 2011), after which it will travel to the Southwest School of Art in San Antonio, TX (Dec. 8 to Jan. 12). The show catalog, Sonya Clark (2011), was produced by the school with support from Snyderman.