Here are three books, all associated with design, which are likely to provoke thought and wonder among visually-literate audiences.

The Infamous Chair; 220̊C Virus Monobloc Arnd Friedrichs and Kerstin Finger, eds. (Berlin: Gestalten, 2010) ISBN 978-3-89955-317-8

This book is at once an homage to and critique of those ubiquitous, cheap, plastic chairs, anonymous and nameless, that litter our environment. Designers, it turns out, have a name for them, derived from their method of manufacture: monobloc, as well as a high degree of animus towards them. The chairs are created from a single, plastic material, in a single process: forced into a mold at 220̊ Celsius (hence, the book’s name). Since the early 1980s they have become a global answer to modernism’s utopian goal of universally-affordable, mass-produced furniture. So why can’t they be found in museum design collections?

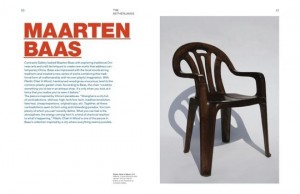

Design critic, Alice Rawsthorn, describes them as cheap, light, portable, waterproof, stackable and easy to clean. Yet their generic form offends educated eyes on the basis of style. The Infamous Chair includes four short essays by critics, writers and teachers of design, a conversation with several chair designers, and photographs of 26 responses to monoblocs by artists and designers. Philippe Starck, Konstantin Grcic and Jerszy Seymour produced serious re-styles of the down-market versions, all in current production (although Seymour’s, the least pricy of the three, still costs approximately 18 times as much as generic monoblocs). But most are snide adaptations that ignore the chair’s undeniable virtues. How amusing is Maarten Baas’ limited edition, monobloc-shaped chair, hand-carved in elmwood, or Tina Roeder’s monoblocs made into limited-edition collectibles by hand-perforating each with 10,000 holes?

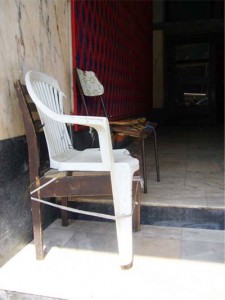

Far and away the most interesting aspect of the book are the photographs of monoblocs in widespread, international use: a bloodied chair in a bombed village east of Falluja; a plaza in front of Jerusalem’s Western wall, full of worshipers in monoblocs; a single chair in front of a yurt in Mongolia; monoblocs converted into affordable wheelchairs in Thailand; and a series of badly-damaged chairs in Cairo, crudely repaired for use. These constitute a visual essay on globalization, material inequities, the creative recycling of the poor and the possibilities of design for the 99% that will interest all readers with a curiosity about unrecorded, everyday life in the far corners of the globe.

Graphic Design; Now in Production Andrew Blauvelt and Ellen Lupton, eds. (Minneapolis: Walker Art Center, 2011) ISBN 978-0-935640-98-4

This book, the catalog to a current exhibition that will tour nationally through 2014, is an eloquent riposte to predictions that e-books will replace the physical things. Just hold it; it’s floppy. Like Proust’s madeleine, it evokes memories, in this case tactile memories of The Whole Earth Catalog, and for some of us, memories of 1968; sure enough, the editors cite The Whole Earth Catalog as an inspiration. The many double-page spreads are as dense as an old Sears catalog; I can’t begin to imagine the eagle vision and nimble thumb-work that would be required to peruse it on a Kindle.

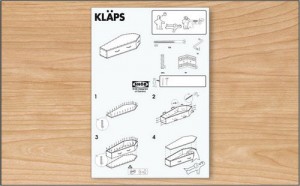

Lest you associate graphic design with ink on paper, the book illustrates tee shirts, axes, chairs, mirrors, dishes, neon signage, burial caskets, Google Doodles, video title sequences, and the Kindle. Which is not to say that it ignores typography, books, magazines, wallpaper, posters, branding material, maps, information graphics, bar codes, or QR codes.

Graphic Design; Now in Production is a visual Whitman’s sampler, fully enjoyable, as well as edifying, for its illustrations alone. But it also contains numerous asides (worked in among the illustrations) and serious essays by 17 authors that address graphic design in specific applications as well as the place of the design professional in the age of Photoshop and desktop digital printing. Designers will surely find it irresistible, and the rest of us will find it full of eye candy and ideas.

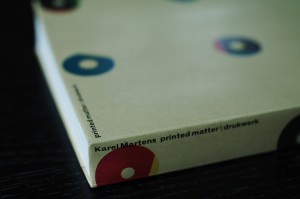

Karel Maartens; Printed matter (London: Hyphen Press, 3rd edition, 2010) ISBN 978-0-907259-41-1

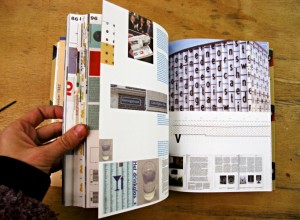

This monograph on the Dutch designer, Karel Maartens (who, with Jaap van Triest, was its designer), is a beautiful object whose very construction provokes attention and delight, from its striking layout to its Chinese binding (double pages, printed on one side and bound with the folded edge on the outside), yielding a volume whose pages have a striking presence as they are turned. It was originally published on the occasion of Maartens’ winning the Dr. A. H. Heiniken Prize for Art in 1996, and covered the designer’s entire oeuvre. The first edition of 1000 sold out, as did a second edition, printed in 2001. This new edition brings Maartens’ work up to date.

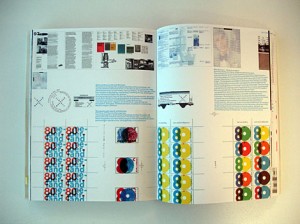

All his projects since 1960 are illustrated and discussed, in enough detail that the book becomes a record of Maartens’ various concerns, including thematic issues for series and journals and design that reinforces meaning, as well as imaginative responses within limited budgets. As someone outside the field who has always been interested in graphic design, I found this particularly useful – it functions as an introductory course in design thinking in practice.

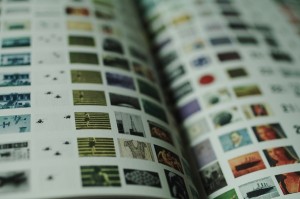

Maartens designed numerous books, posters, calendars, postage stamps, telephone cards, signage, and the official newspaper of the Dutch government, the Nederlandse Staatscourant. His work exhibits a freedom in respect to page margins that is a mark of Dutch design, although he was never associated with a particular design group or took a theoretical position. His design is extremely labor-intensive and avoids default formats – each commission is bespoke. His most widely-distributed work is probably his design since 1990 for the Dutch architectural publication, Oase, and he is eloquent about crafting individual responses to the journal’s varying thematic issues. The book includes an essay by Maartens and an interview with him, as well as essays by four authors about aspects of his work. It also includes ten virtuosic pages of bibliography of book designs, chronology and list of writing about his work, which demonstrates remarkable clarity, despite the huge volume of information and extremely small type.