2011 was the 100th anniversary of the birth of Marshall McLuhan and to mark the occasion, Pratt held an exhibition, Resonance; Looking for Mr. McLuhan, curated by Berta Sichel, director of the department of audiovisuals and chief-curator of film and video at the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, and Mariano Salvador, also of the Reina Sophia; it ran Oct. 21-Dec. 21, 2011. In the 1960s McLuhan was widely derided by fellow academics for his extremely popular books that dealt with the implications of changing technology upon human relations. Forty-five years after the publication of Understanding Media (1962) and The Medium is the Massage (1967), we can appreciate McLuhan’s prescience about the impact of technologies he didn’t live to see.

Work by sixteen artists and collaboratives, produced from the 1960s to the present, reflected the continuing relevance of McLuhan’s ideas; all addressed aspects of the impact of changing technology, from letter-writing and typing to the World Wide Web. As one might expect from the subject, much of the work utilized technology (largely video, but one piece also incorporated the Web), although the range of media was broad, including a collage of typewritten texts that were stitched together by hand (Elena del Rivero’s Mended Flying Letters, 2010), artists’ books (Wolfgang Plöger’s Google Image Search (Map), 2006, which consisted of several volumes of images transcribed from a Google search for map), photography, and small-scale sculpture (Joan Rabascall’s 6″ model, Monument to Mobile Television, 1974). It was a challenging and unexpected selection of work which avoided conventional categories.

The exhibition emphasized the physical interactions between people and technology with changing sensual experiences: Plöger’s books were perused by viewers seated at a table, turning pages; Magdalena Pederin’s The Name is an Anagram was shown in a darkened space where multi-dimensional images created a changing, immersive environment; Nam June Paik and John Godfrey’s Global Groove was a single-channel video, and having to standing to watch it was a reminder that the pioneering work was made in 1973, long before MTV brought music videos to our livingrooms.

The astonishing sound production in Ignacio Uriarte’s video, The Story of the Typewriter (2011), was human: the actor, Michael Winslow, seen creating the differently-inflected sounds of a series of typewriters, with remarkable fidelity. Winslow’s virtuosic performance emphasizes the multi-dimensional aspect of much technology; typewriters were designed to produce text, yet also generated sound. It’s hard to imagine how this work might be read by someone of the computer generation; I guess it will need an explanatory label. I had a similar experience, some years ago, while looking at an Oldenburg and trying to explain to a 10-year old what a diaper pin was.

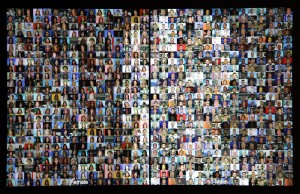

Reporters with Borders (2007), Raphael Lozano-Hammer’s interactive video work, was activated by the presence of a viewer, whose silhouette appeared on the screen filled with tiny images of Mexican broadcasters on one side, Americans on the other, who began to speak; they produced simultaneous, cacophonous newscasts, yet remained segregated by country.

Chris Petit’s Content (2009) was a 76-minute video, and its length as well as its content emphasized the dimension of time. I had expected to watch a few minutes, but was so seduced and mesmerized by its beauty and subject matter that I stayed for the entirety. Petit interweaves several narratives that concern communication, self-presentation and masquerade, aging and responsibility, set within the context of a road movie where geography is equated with memory.

Marshall McLuhan’s misfortune was to be decades ahead of his time, with a vision so accurate that his ideas now seem commonplace. It is well worth commemorating his early understanding of the profound effects of changing media, and this thoughtful exhibition was a suitable tribute.