Steven Baris and Kim Beck’s work at Pentimenti is intriguing for me because the artists’ subjects speak to the facts of life all too familiar to me as a New Jersey denizen: rampant construction, and the ubiquitous presence of the exurbs. Both artists have been covered on artblog previously.

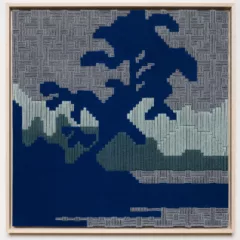

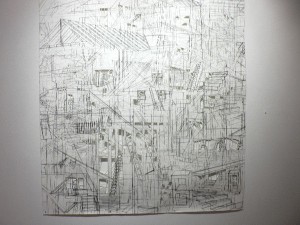

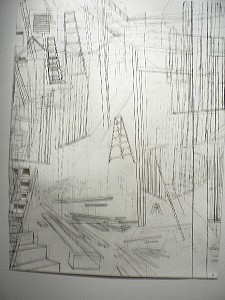

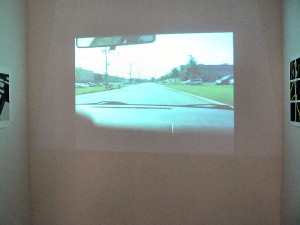

Kim Beck’s “Built Futures” — large drawings in graphite, charcoal and cut paper — surveys peripheral and suburban spaces, especially the built environment, which brings “the banal and everyday into focus.” Philadelphia-based Steven Baris’ “Stations of the Cube” is an exploration of ”placeless” spaces. The a self-made exurban theorist’s video installation “Exurban Archipelago” supplements his mixed media works.

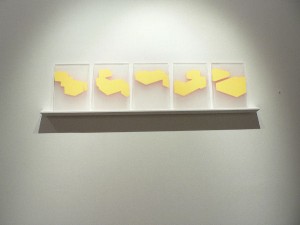

In 2008, writing of Beck’s work, Libby praised her exploration of the arbitrary placement of city green spaces. Beck’s past projects, such as “Holeymoley Land,” have been described as “almost manic…a cacophony of signs, street lamps and architecture…the urban equivalent of a rainforest.” There are strong echoes of that randomness in the drawings in “Built Futures.” Here, Beck has laid out meticulous representations of progress; beams, planks, and ladders abound. However, the impracticality of the construction becomes immediately obvious. What could have been simple exercises in draftsmanship instead are repetitive, convoluted, and ultimately functionless architectural motifs, Rube Goldberg-like environments of construction for construction’s sake. The windows look out on only the blank wall behind them; the viewer is confined to the hectic space, and compelled to make sense of disorder.

Having grown up on Indian reservations, Baris makes ample use of his fascination with the contrast between this type of space and the most built-up part of the continent.

The exurban form that intrigues Baris the most is the distribution center, the vast warehouse spaces that supply the retail and wholesale establishments where we shop. With their equally-vast parking lots, they are an ugly necessity of modern life. Baris was transfixed by their presence along the NJ Turnpike, and “Stations of the Cube” attempts to discover their spatial effect on people. Baris has gone to extensive, even obsessive lengths in the past to modify outmoded definitions of the exurbs as places inhabited solely by the wealthy. In interviews, he has spoken passionately about the ways in which the mid-20th century binary mode of urban and suburban has grown to include the exurb, in which population centers – and peoples’ lives – hew to expressways rather than cities.

Baris’ paintings and video raise many questions, but he is interested more in the exurbs’ geometric qualities and architectural uniqueness than in using the work as a platform for his beliefs about whether they are a positive or negative force on their surroundings. He leaves that to the viewer. Having grown up near the exurbs of NJ, my consciousness has always included this exurban presence, and Baris’ work gave me the idea that the exurbs are built in a way that excludes other spatial possibilities. Whether they are Baris’ highway-side distribution centers, or complexes of office parks and man-made lakes, exurbs consume a monstrous amount of the landscape, and little is allowed to break the continuity.

Although the artists examine man-made spaces differently, their explorations underscore the resounding smallness of human life when up against the scale of the built environment.