I finished reading the collected writings of Suzanne Lacy (see below) on the plane to the 100th Annual Meeting of the College Art Association (CAA) , held from Feb. 22-25 at the Los Angeles Convention Center. I was excited that I would finally see the artist in action. Lacy is a pioneer of what has come to be known as social practice (sometimes termed participatory art, community art, situational art or social sculpture), and founded an MFA program under that name at Otis College of Art and Design in 2007. Since the early 1970s she has produced work consisting of socially and politically engaged events, often developed and carried out with the active collaboration of other artists, and always engaging members of the concerned communities.

While her work has been recorded via photographs and writing, in contrast to other artists with performative practices, Lacy has never treated those documents themselves as art, nor has her work generated artifacts to be exhibited (although, having written that, I just saw photographs of several of Lacy’s pieces on exhibit in State of Mind; New California Art Circa 1970 at the the UC Berkeley Art Museum; they were all lent by the artist, and I suspect she considers them documentation). To experience Lacy’s work you had to be there, and I’d never had the chance.

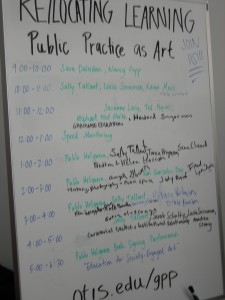

As an intervention at the CAA conference, the Otis Public Practice program conducted an ongoing series of seminars in the Convention Center’s lobby: Relocating Learning; Public Practice as Art. The discussions took place with participants sitting in circles, a videographer recording the event, and a changing cast of observers as conference attendees walked past. A colleague told me that Lacy had asked him to participate, and he simply couldn’t turn her down. Lacy was in her metier as teacher and enabler.

On Friday afternoon I sat in on a discussion about curating such experimental, ephemeral, and interactive work. Chaired by Sally Tallent, visiting professor at Otis and Chief Executive Artistic Director of the Liverpool Biennial,the discussion addressed how invitations to perform in museum spaces might affect the nature of public practice. The discussants included students, several faculty members, and two curators involved with the subject: Sarah Schultz, newly-named Curator of Public Practice at the Walker Art Center and Aandrea Stang from LA MoCA (both of whom present events, but do not acquire documents associated with them). Students were concerned that inherently open-ended practices might be stifled within the institutional context, and there was talk about the unpredictable outcomes of experimental work. Both curators said they felt equally responsible for the artists and their audiences (as well as their institutions, of course). What became clear is the inevitable ongoing education for all participants when experimental art practice enters the bureaucratic and inherently conservative space of the museum.

Suzanne Lacy Leaving Art; Writings on Performance, Politics, and Publics, 1974-2007 (Durham: Duke University Press, 2010) ISBN 978-0-8223-4569-5

Lacy, who initially studied psychology, cites two major influences on her decision to become an artist and choice to work in a socially-engaged manner: her participation in Judy Chicago‘s Feminist Studio Workshop, and her study with Allan Kaprow – a powerful start. The current interest in performance art of the 1970s has managed to downplay the feminist aspect of much of it. This book is a useful reminder of just how crucial, one might say dominant, women were in performance art during that period. For a woman to participate in performance was inherently a feminist stance. The personal was always political.

Her topics have included women’s safety and the violence of societies which tolerate rape, homelessness, urban renewal, the ethics of organ donation, images of women in popular culture, and ageing, among others. Lacy thinks viewers did not always appreciate the aesthetic dimensions of her work because of its overtly social subject matter, and she analyzes her artistic thinking as it intersected with the social, political and communal aspects of her practice.

The volume includes scripts used in performances as well articles published previously, but largely in magazines and journals with modest circulation. It not only gives a clear progression of the trajectory of Lacey’s work, but includes her ongoing questioning of just what an art of social practice might accomplish and how it should be judged; as Lacy puts it, she explores political performance art, including media deconstruction, personal/political experiences, “results” of art, and differentiations from other practices such as local politics or anthropological research. She also gives a clear description of providing content designed for the media, in order to control the way the message is disseminated. The book should be required reading for all artists interested in work with political content as well as those who site their work beyond the precincts of art.

Doin’ It In Public; Feminism and Art at the Woman’s Building, Ben Maltz Gallery, Otis Institute of Art and Design

I was lucky to catch the final week of Doin’ It In Public; Feminism and Art at the Woman’s Building at Otis (October 1, 2011 – February 26, 2012). The Women’s Building is always referenced in histories of feminist art and advocacy, and this was the perfect way to understand the breadth and significance of L.A.’s contribution; Suzanne Lacy was very involved with the institution from its beginnings. Founded in 1973, the Women’s Building became internationally-recognized as a site for instruction, collaboration, exhibitions, performances, literary events, film and video art, conferences, extension programs and community events. Course topics ranged from Assertiveness Training for Women, a Tax Workshop, and Women’s Environmental Fantasies to Art Criticism, Video and The Lesbian Nove

The exhibition functioned as an extraordinary, three-dimensional scrapbook of documentation and ephemera: short videos, black-and-white photographs, and the often poorly printed flyers and publications that could be turned out on low budgets. I’d seen some of the material in reproduction, but there’s nothing like the real thing to convey the enthusiasm, sense of discovery, collaborative spirit and endless hard work involved.

It’s astonishing and impressive that someone saved and archived all this material. Much is housed at Otis, but the exhibition curators did a herculean task in locating and borrowing items housed elsewhere, and displaying so much detailed content with both clarity and a strong sense of its visual impact. The installation included enlarged photographs, actual works of art, places to sit and read, and numerous videos to enliven all the printed documentation and photographs.

The exhibition is supplemented with a two volume compilation of essays by 21 authors: Volume I: From Site to Vision: the Women’s Building in Contemporary Culture, and Volume II: Doin’ It In Public; Feminism and Art at the Woman’s Building (L.A.: Otis College of Art and Design, 2011) ISBN 978-0930209223.