As recent national news has made painfully clear, ours is not a post-racial society, and much as I’d rather not see African American artists exhibited in the context of their common racial background, such exhibitions still have a place. That place is particularly important in Philadelphia, where the extent of art world segregation still surprises me; among the mainstream (read white) institutions, the Fabric Workshop Museum and the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts (PAFA) have a strong history of supporting artists of color; unfortunately the color line extends to many of the galleries and their audiences, as well.

After Tanner; African American Artists since 1948 (through April 15) was organized as a complement to the Henry Ossawa Tanner exhibition downstairs (which I wrote about on Feb. 5, 2012). Only a few of the artists knew Tanner, but his international success made him a likely a role model for all of them. This is the largest representation of work by African American artists I’ve seen in Philadelphia since moving here in 2003, and although there are notable omissions, it is an important exhibition whose fifty works include the historical and stylistic range of its ambitious subject. It encompasses academic painting of the 1940s, modernist abstraction, political art that came out of the 1960s Black Power movement, and a range of recent work by Glen Ligon, Willie Coles, Kara Walker, Layla Ali, Quentin Morris and others.

Curator Robert Cozzolino explained that he likes to use the second floor of the new building to exhibit work related to the exhibition on the first floor, primarily showing work from PAFA’s collection. Would that all the paintings in After Tanner were PAFA’s! A number of the private loans are clearly museum worthy, and I can only hope that they enter PAFA’s collection some day. The exhibition is hung chronologically, and paintings by Edward L. Loper, Eldzier Cortor, Louis B. Sloan and Hughie Lee Smith reflect the figurative style generally favored by American artists in the 1940s and best known through the work of regionalists, such as John Stuart Curry and Grant Wood, and urban painters such as Edward Hopper and Reginald Marsh. All are obviously trained artists, and only Cortor and Smith include African American figures. Smith’s wonderful and subtle Conflict (1944) refers to racism in a manner that conveys complexity, rather than a simple message and has the political punch of the best work of Ben Shahn. The small painting is a gem, much the strongest of the group, and I hope PAFA manages to acquire it.

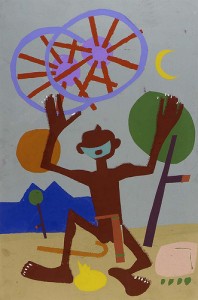

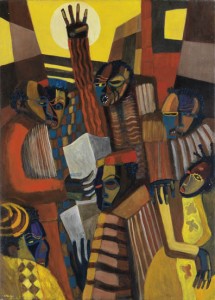

Another important painting that I’d love to add to the collection is Charles Alston’s massive, hieratic composition, Symbol (1953). The label credits the artist’s interest in Mexican art, both ancient and modern, but I suspect he also knew the work of Wifredo Lam and Max Beckmann. Raymond Saunders’ powerful portrait of Jack Johnson (1971), owned by PAFA, is a sophisticated example of figuration brought up to date. The boxer is shown armless (or with arms behind his back), which is possibly a reference to the racism that hampered Johnson’s career. Cozzolino described it as made in a wave of literary, musical, political and artistic contributions to the Black Power movement and that is certainly one of its contexts. It is a political painting, representing Saunders’ assertion of an important and transformative figure in American history …. That kind of urgency and confrontational image is less in evidence today for a lot of reasons.

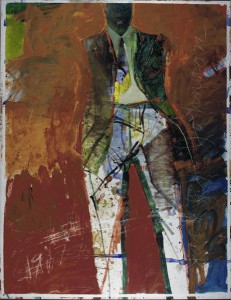

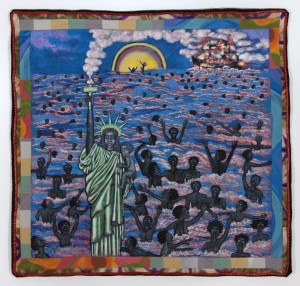

Faith Ringgold’s modern figuration draws on both vernacular story-telling and women’s craft to create a biting, political commentary . We Came to America (1997), from the series The American Collection, shows a black Statue of Liberty holding a black infant, creating an image of a secular madonna; Africans who escaped a slave ship await rescue from the water surrounding her. It is a banner protesting exclusion and an emphatic re-telling of history from the bottom up. Redneck Birth (1961) by Norman Lewis is very much of its period, employing large scale calligraphic brushwork also used by Bradley Walker Tomlin but massing the paintwork to create a figure out of abstraction; but I wish PAFA also owned one of his small, allover paintings of the 40s (which are gutsier versions of Mark Tobey’s allover calligraphy).

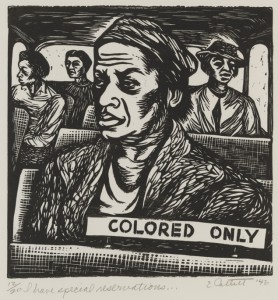

The exhibition expands into the gallery at the front of the building (filled primarily with sculpture) with works by Nick Cave, Bettye Saar, Elizabeth Catlett (one of the strongest of her sculptures) and many others, and in the hallway on the ground floor, which displays recent acquisitions by Mark Bradford and Mickalene Thomas.

I’ve been reading a very interesting, academic book that, to use the current jargon, problematizes my response to After Tanner: Making Race; Modernism and “Racial” Art in America by Jacqueline Francis (University of Washington Press, 2012) ISBN 978-0-295-99145-0. Francis looks at the response to three artists of minority background during the 1920s-30s: Malvin Gray Johnson, Yasuo Kuniyoshi and Max Weber. The work of all three was described as Racial Art at the time, a term which carried expectations that the artist took his own people as subject, did so with an insider’s knowledge, and with a form of expression that reflected his background (e.g. that there was an African American, Oriental and Jewish art). While the terminology has fallen out of use, the idea that African American artists should represent their own, and in an exemplary manner, certainly endured for a long time. One recent indication was the very negative reaction of a number of African American artists to the work of Kara Walker, as published in a book edited by Howardina Pindell, Kara Walker No/ Kara Walker Yes/ Kara Walker ? (Midmarch Press, 2009).