Martha Wilson Sourcebook; 40 years of reconsidering performance, feminism, alternative spaces, Martha Wilson, ed. (Independent Curators International 2011) ISBN 978-0-916365-85-1

Martha Wilson’s sourcebook is filled primarily with the writing of others, through which Wilson traces important influences on her life and art, and documents the New York alternative art scene since the 1970s. She has culled excerpts from writing that will be familiar to all women who were young during the 1970s, and will give younger readers a good idea of the books that were on everyone’s shelves at the time. A partial list of authors includes Simone de Beauvoir, Linda Nochlin, Shere Hite, and The Boston Women’s Health Collective. It was a time of broad public discussion about sexuality and women’s current and potential position in public, as well as private life.

Wilson includes excerpts from writing about experimental art since 1970 by other artists, critics and historians including Lucy Lippard, Howardina Pindell, Dick Higgins and Mira Schor, and illustrates work by a number of other women, including Linda Benglis, Adrian Piper, Carolee Schneemann, and Ida Applebroog.

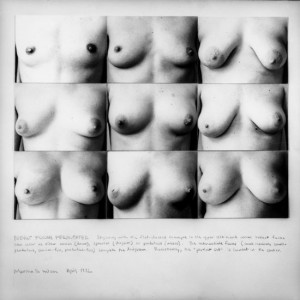

This is not to say that Wilson’s voice is absent. The book includes extensive illustrations and scripts of Wilson’s photo-based and performance art, much of which drew directly from her own history. Her voice is sharp, politicized, and often very funny. A work which Lucy Lippard included in c. 7500, an exhibition which began at Cal Arts and traveled to five other venues during 1973-74, shows a grid of photographs of the breasts of twelve women and a text explaining the concept behind their arrangement: beginning with the flat-chested example in the upper left-hand corner, breast forms can appear as conical (down), spherical (diagonal), or pendulous (across)…. Breast Forms Permutated (1972) skewers men’s preoccupation with women’s breasts, communally-established cannons of beauty, and the photographic style, impersonal language, seriality, and rule-based decision-making of much conceptual art at the time.

Wilson reproduces the entire c. 7500 exhibition catalog, which consisted of four index cards with Lippard’s introduction and general information, then individual cards designed by each artist, all of whom were women (with the exception of one collaboration that included men). Among them were Laurie Anderson, Eleanor Antin, Agnes Denes, Adrian Piper and Mierle Ukeles. This will be extremely useful for the many readers who have never seen Lippard’s exhibition catalogs of that period; not only are they rare, but the format of unbound index cards makes them difficult for libraries to handle (note: I’m looking forward to a book about these exhibitions, From Conceptualism to Feminism: Lucy Lippard’s Numbers Shows 1969–74, which is due out this Spring from Walther König/Afterall Books)

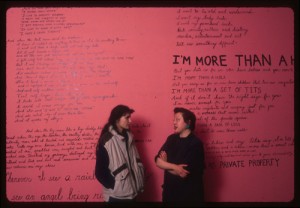

The book also documents Wilson’s work in founding and operating Franklin Furnace, a non-profit space which presented and preserved avant garde art forms that mainstream institutions avoided because they were ephemeral and/or politically challenging; it was known for sponsoring performance art and temporary installations, and for having the most important archive of artists’ books in the U.S.. Wilson tells her own story, enriched by C. Carr’s timeline of events surrounding the National Endowment for the Arts during the culture wars of the 1980s-90s (which affected Franklin Furnace as it did all progressive arts institutions), and Alan Moore and Debra Wacks’ detailed study of the interaction between the art world and real estate in the area around Franklin Furnace.

The format itself is a step back in time, appearing to be a collection of xeroxed material: some double-page spreads in reduced size (which require the book to be turned by 90 degrees), others full-sized but upside down; the reverse of some articles is blank and writing is shown bleeding through on others. Each selection retains its own graphic style, and correspondence includes letter-head and stamps to indicate date of receipt. And it is all printed in glorious black and white (or variations of grey, for many of the xeroxed copies)! Much of this is lost when the same articles are accessed in digital form, and the look of the period is an inextricable part of its visual culture.

- This selection of multiple voices turns out to be an inspired way to document the evolution of Wilson’s life, art, and organizational work. It’s also a good read. It adds to the bookshelf of recent works by several other women who participated in the downtown art scene in New York City since the 1960s, including Marcia Tucker’s A Short Life of Trouble , Carolee Schneemann’s correspondence, and the anthology edited by Julie Ault, Alternative Art New York, 1965-1985. Addressing much of the same material, the recent film by Lynn Hershman Leeson, !Women Art Revolution (!W.A.R.) adds visual documentation to the record.