The Bushwick neighborhood of Brooklyn has been a haven of cheap rent for artists and newcomers to New York for at least the last five to ten years as Williamsburg increasingly became overly expensive. The venues of Bushwick are multitudinous: from music lofts, to clean galleries, to someone’s studio. A recent twist in the neighborhood’s development was the opening of Chelsea gallery Luhring Augustine’s satellite space in February.

The grey painted façade of the building blends in with its industrial neighbors while standing out as mint construction. I asked the gallery attendants sitting at a desk in the lobby what was the appeal for the gallery in opening the new space. The pair explained that Luhring Augustine has owned the building for about a year and that it has been a warehouse most of that time. The owners wanted to use it for projects they “could not” undertake in their Chelsea gallery.

The inaugural exhibition is Charles Atlas’ The Illusion of Democracy. Atlas, a film and video installation artist, who has been working in New York since the early 70s, doesn’t have gallery representation in New York and has not had a major exhibition here since 2003. He is not on Luhring Augustine’s roster of artists, but the show in Bushwick is up for three months—a rarity for a commercial gallery.

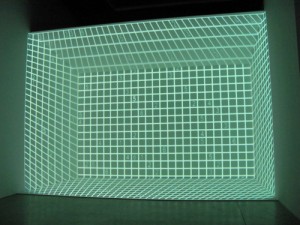

The exhibition space is a large room with an exceptionally high ceiling that one enters after passing through the entrance vestibule. With the lights out, it is akin to a ceremonial cave. Atlas exhibits three video animations, which are individual pieces, but in concert produce a full theatrical experience. The components of each video are the same—the digits 1 through 6 in white on a black ground—but their animation and installation properties differ. The projections reach from floor to ceiling and invoke the simple illusions of spatial perception (numbers grow smaller and larger as they move forward and backward), creating for the viewer the absorbing experience of being in a movie theatre (without seats). With minimal elements, Atlas forms a compelling sense of time and narrative; I felt myself wondering at every moment what would happen next. The digital effects employed in Painting by Numbers and the association to stars in deep space evoke the aesthetics of mysticism, but the austere semantic ingredients link the video installations to the work of Mel Bochner more than anything else.

Closer to the Jefferson St. subway, actually just over the border in Ridgewood, Queens, is Regina Rex, an artist-run gallery, which in January was featured in the Wall Street Journal. Until April 8th, the paintings of John Almanza and sculptures of Dave Hardy are on display. Both artists’ works pay tribute to process. Almanza’s oil paintings on canvas build on Gerhard Richter’s scraped paintings, although Almanza’s are more procedural and less alchemical. As I can gather from the press release, the artist uses a plywood tool that simultaneously adds and subtracts paint from the canvas when dragged over the surface. The result is cool and composed—a little too much for my taste.

Dave Hardy’s sculptures, on the other hand, are a surprising and nail-biting combination of materials: found glass, wood, metal, and foam. He creates stacked towers with little to no adhesive (using dado cuts instead) that carefully play within gravity’s territory, like large glass houses of cards. The foam acts as padding to relieve tension on the glass and the viewer’s nerves. Hardy’s forgiving choice of imperfect materials (chipped glass embellished with masking tape and permanent marker scrawls) contrasts with Almanza’s strict, calculated approach and lends his work a desired sense of play and character. Gravity is one of Hardy’s most important materials and his sculpture succeeds most in its acknowledgement that the future is uncertain.

Play is also the theme of the exhibition, Big Reality, curated by Brian Droitcour, at the multimedia venue 319 Scholes, dedicated to the presentation of new media and digital arts. Big Reality’s premise is centered around fantasy role-playing games. The notion it tries to untease is the process of fantasy which a gamer necessarily undergoes in acting through an avatar. The curator’s thesis seems to be that digital technology users (particularly Gen-X, Y, and Z-ers) constantly mediate between fantasy and reality on a moment to moment basis. The exhibition’s text suggests: “…the RPG codes a particular, specifically contemporary relation of the self to the world, one in which technology and abstraction, fantasy and play are deeply implicated in the routines of everyday life.”

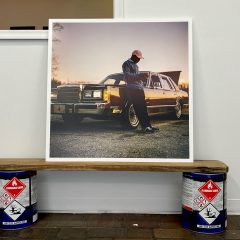

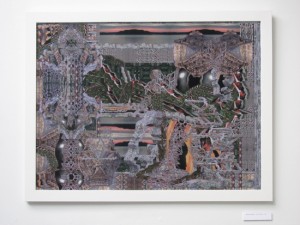

The work does not favor the tangible or the digital—they are considered equal in the exhibition, much like how the Millennial generation (of which I am a part) would be dismayed to have to choose between their laptop and the greater world. Notable pieces in the exhibit include selections from Timothy Hutchings’ Plagmada (Play Generated Map and Document Archive), plans scrawled on graph paper to help gamers understand a “shared imaginative space” (quote from Hutchings’ site); Brody Condon’s Lawful Evil, a staged performance of a D&D game complete with bottles of sugary drinks; Laura Brothers’ Stuffy Head Portrait, a pixel composition nostalgic for Gameboy graphics; and Brenna Murphy’s digital collages that morph the Oregon landscape into fractal nightmares.

While the concept of the show is particularly relevant, the exhibition suffers from too much on display. For a rigorous and contemplative concept, the curator should have realized the power of the individual pieces and the space they require to be absorbed by the viewer. In this one regard it felt amateur.

319 Scholes included, Bushwick is where much of the most promising and in-touch artwork is displayed in New York City these days. Luhring Augustine’s move into the neighborhood may or may not mark a significant shift in its profile. Artists are watching nervously to see what will happen and where we will be able to afford studios next.