The complex drawings adorning the walls of Rebekah Templeton Contemporary Art in Fishtown have lives of their own. Without the artist’s hand as part of the equation, any of these heavily contrasted, black-and-white forms could easily be growing out of a patch of soil or spreading across the agar of a Petri dish. The fact that these creations are not multi-cellular organisms and are actually comprised of deliberate pencil or ink markings makes them all the more remarkable.

Bearing the name Organon as a means for the process of investigation, the show examines synthetic, creative, and human processes that often mirror the biological and organic processes at work in the world around us. Should there be such harsh distinctions between what is “human” and what is “natural”? What exactly defines the boundaries between the synthetic world of computers and machines as opposed to the mechanisms of plants and animals? There are big questions at the forefront of this show, but this is certainly not to dismiss the artistry of the drawings themselves; they are splendidly convoluted and yet inviting and familiar.

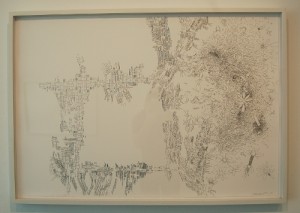

Colin Keefe has a pair of meticulous pen drawings that are extremely easy to get lost in. They appear as a midpoint between aerial shots of urban areas and bacterial cultures. It’s as if a large swath of land from the islands in Dubai somehow began to grow on its own volition. Sections of the patterns are organized into grids and right angles, but as the eye follows their path, they begin to melt into more winding and biological masses. Anyone who has flown in an airplane can easily see the parallels between urban sprawl and microorganisms’ reproductive habits. It would be going a bit far to assume Keefe thinks humanity is a virus; however, the way his forms fan out across the paper does tend to imply that even the most industrial of constructions is ultimately a byproduct of life.

Sarah Laing also works in pen and ink, but her drawings are more plant and animal hybrids than anything remotely mechanical. The organisms in her pieces resemble cornstalks or some type of tall weeds at first glance. At further inspection, the details actually look like they have joints, bones, or even skin. It’s as if human fingers or other animal-like appendages are emerging from within the plants’ stems and leaves. Even the most divergent of life forms actually share a huge portion of their genetic makeup. The difference between a dandelion and a dog is relatively small as far as DNA is concerned. Laing seems to be of the mindset that – whether animal or plant, human or otherwise – all life shares an astonishing number of characteristics even in the face of its diversity.

Of the three artists in Organon, Alana Bograd is the only one to work with pencil. Her drawings are the most numerous in the exhibition and also the smallest. They are very freeform and seem in some ways like the amorphous entities that result from automatic drawings. All of the warped images are extremely surreal and every one also contains representations of breasts. In this way they are maternal and life-bestowing, as well as mammalian. They are sexualized but not sexy, curvaceous as well as somewhat creepy. All of them are headless but also possess leaves, sharing some of the hybrid characteristics of Laing’s artwork.

All of the creations in Organon play off of biological themes and complement each other in powerful ways. The revelations in studying the works individually and in comparison to one another are almost endless, while the patterns are fractal and cyclical in the most visually stimulating of ways. Rebekah Templeton proves its curatorial prowess once again in this show that is not to be missed.

The show is up until May 26.