Time, like death, is a subject certain to remain of eternal interest to artists, scholars, and the public at large; two exhibitions currently in Philadelphia approach the subject very differently. The delightful Tempus Fugit; Time Flies at the American Philosophical Society Museum (APS Museum) through December 30, is an exhibition conceived of as poetry, rather than the more usual form of scholarly prose. The artist Antonia Contro has selected works from the Philosophical Society’s collections that deal with aspects of time, and sensitively juxtaposed them with work of her own. She is interested in aspects of time explored by scientists from the Renaissance to the present, and even more interested in the metaphors they have employed to present their findings.

Even at the first glance, it is obvious that this is not an ordinary exhibition; the cases are arranged as an open book, and the sound of turning pages can be heard in the background. So one naturally turns to “read” the exhibition from left to right via display cases which, like chapters of a book, are each named.

The first case, a tempo (in time), holds a book by Joseph Priestly, published in 1778, which includes a multi-fold insert that Contro has extended to look like an ancient scroll. It was Priestly who first employed the metaphor of the timeline (one which suits scrolls better than codices – or conventionally-bound books). Since line is the basis of drawing, which itself is the beginning of all traditional visual art, the association of time with a line has particular resonance for artists.

Case two, Sognando (dreaming), introduces wonder and even magic; what looks like a magician’s wand turns out to be a glass tube used by Benjamin Franklin in his electrical experiments. It is set in front of Heaven’s Dome, a back-lit aluminum work by Contro that reads as the sky at dusk. At the bottom of the case sits the astronomer Cromwell Varley’s notebook, open to his illustration of Donato’s Comet. Varley, it turns out, believed in spiritualism.

The third case, Adagio (slow movement), brings in geological time and the sense of insignificance that we inevitably feel when attempting to grasp such an enormous scale. The fourth, Nocturne (Written for the Night), is an essay on spheres, in black and white, celebrating the beauty of nature’s geometry.

Case six, Crescendo (growth), explores the multiple uses of tree diagrams: the tree of Darwinian descent of humans and other vertebrates, an anatomical depiction of the human circulatory system as a tree form, and most surprisingly, a tree diagram created in 1961 to trace the development of the modern computer. I suspect Contro was rightly amused to see cutting-edged engineering outlined in the same format used to track the Biblical genealogy of Christ, with the Tree of Jesse. Her humor is also evident in Canto (chorus), where she has included an artifact with the label Coiled piece of wire, maker unknown, 1893. Such unidentified objects are the bane of registrars and collection managers, unlikely to be used yet dangerous to dispose of. This is surely the only occasion on which this modest orphan will make an appearance outside the storerooms.

Contro’s exhibition takes full advantage of what artifacts can teach, revealing their aesthetic as well as their historical and scientific value. But her most important contribution is to remind us that science, like art, begins with an act of the imagination,

The APS Museum is hosting several events in connection with the exhibition, including discussions, dance and theater performances, and during the first ten days of June, a celebration of the Transit of Venus (where the planet appears between the Earth and the Sun; an arrangement that won’t occur again for a century. All can be found on the museum’s website.

Maya 2012; Lords of Time is on view at the Penn Museum through January 13, 2013; timed tickets are available on-line, or at the museum. The exhibition was certainly conceived as didactic prose; the question and answer format suggests that much of it is directed at children, and it has borrowed some conventions of tabloid journalism. It came about because Penn Museum archaeologists have been excavating a major Mayan site at Copan, Honduras since the early 20th Century. That should have been enough of a pretext for an exhibition. Instead, someone had the idea to make it sexier by invoking a series of misconceptions about the Maya. The primary misconception is that Mayans of the Classic period (250-900 C.E.) expected the world to end in 2012, an apocalyptic idea originating in books that are not to be found in university libraries.

The U.S. has no shortage of end-of-the world stories and no need to look South or to the past for another. The exhibition’s repeated emphasis on miss-conceptions gives them much more prominence than they deserve. In addition to the labels’ questions and answers, there are a number of interactive displays; one allows visitors to write their names with Mayan glyphs, another to translate their birth dates from the Roman calendar to the Mayan, and a third to explore the archaeological site at Copan.

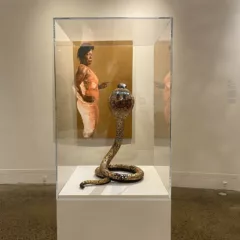

A number of extraordinary artifacts make the exhibition worth visiting for aesthetic interest. The first object in the exhibition is a hand-sized shell,exquisitely decorated with tiny, figurative images that resemble those painted on Mayan ceramics and in incised stone decorations. These were made with minute inlays of jade and shell, and I’ve never seen anything like it; a museum staff member told me there isn’t anything else like it. Just beyond are two of the florid, fearsome, stone scepters known as eccentric flints; their fierce profiles make it clear that their bearers meant business. And a room further on has a number of very fine ceramic pieces: polychromed, lidded vessels, a container in the form of a deer, and the majestic, sculptural covers of three censers. These last depict several generations of royalty, decked out in ceremonial finery, from a period when Mayan kings were thought to embody time – hence the exhibition title, Lords of Time.

Maya 2012; Lords of Time goes into great detail about the Mayan numerical system and calendar (in fact, calendars – they had several) and method of citing dates. What isn’t addressed are the implications of having such a calendar and how this might have distinguished the Maya from their neighbors. The quality of craftsmanship of Mayan objects and architecture indicates highly-skilled, specialist artisans, hence a highly-hierarchical society; we are clearly seeing art made for the 1%. But what of the craftsmen and their technology? There are fine carvings of hard stone, fired ceramics of great size and manuscripts done by virtuosic scribes (with very acute eyesight); I’d have been interested to learn about their techniques and tools, as well as how their craftsmanship evolved.

The exhibition does make extremely good use of reproductions – of architectural reliefs and large sculpture that can’t be moved, and copies of two of the three or four – the number is debated- extant Mayan texts. The finer is in Dresden, the other in Madrid; they are shown in true scale reproductions, and the Dresden Codex is also enlarged to about 8 feet tall, which enable a close viewing of the scribe’s virtuosity. The codices were made of bark paper (the Mayans likely developed paper earlier than the Chinese, who introduced paper into Europe) and while the term codex is used to describe them- they were not bound, as the term codex is used for European books and manuscripts, but consisted of pages arranged as accordion-folds (what Europeans term a leporello).

A series of interactive videos introduces archaeoplogists, epigraphers and other scholars who worked on the exhibition; another series of videos depicts a group of modern Mayans, whose post-Colonial history has been as difficult as that of most colonized, indigenous peoples. The current situation of Mayans is an interesting topic, but one with little obvious relationship to the ostensible theme of the exhibition, the Classic Mayan concept of time. Interactive, in the case of the videos, means visitors can press one of several buttons to answer pre-selected questions; they don’t exactly encourage open-ended inquiry, nor do they contribute much hard information to the exhibition. I suspect most of them were designed to appeal to children (and children who do their homework with the tv or music playing, as multiple, often overlapping soundtracks are audible throughout the exhibition). Since I didn’t have a child in tow, I can’t judge the response.

There are low-tech and rather more interesting activity hand-outs which enable young visitors to follow the work of one of the many professionals (curator, conservator, archeoastronomer,…) involved with the exhibition. This sort of educational hand-out could well be designed for many of the Penn Museum’s permanent installations, encouraging visitors of all ages and levels of expertise to explore one of the great museums in the country. The Penn Museum needs to overcome its location between a sports stadium and a major hospital district, with no foot traffic in front of its entrance. It should probably open one of its entrances directly opposite HUP (the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania), for visibility. It also needs to address the perception that it is hard to get to and/or to find. It is adjacent to a parking garage, and is only a short walk from the trolley stops at 34th and 37th Streets.

The museum has organized an extensive program of lectures, children’s activities, musical evenings and other events associated with the exhibition as well as a special menu at the museum’s café. All are described on the museum website. The current issue (Spring 2012, vol. 84, no.1) of the museum’s magazine, Expedition, is devoted to the exhibition, with articles on many topics that the exhibition cannot cover in detail.