Juan Downey was an important, yet under-recognized pioneer of video (and worked in a variety of other media), who was active in the downtown art scene in New York, where he moved in 1967 and remained until his premature death in 1993. A substantial body of his work has not been seen in the U.S. in decades. The Bronx Museum of the Arts and MIT’s List Visual Art Center have organized this large and stunning, first U.S. survey, Juan Downey; the invisible architect, which is on view in the Bronx through June 10. If you are interested in video, video installation, participatory art, interactive technology, subjectivity within documentary, the political possibilities of art, post-colonialism, communal societies, and/or art arising from meditation and trance states, you may well be amazed to find work addressing all of these current concerns, that was produced between 1967 and 1993. I can’t think of another artist of the period whose work looks so fresh.

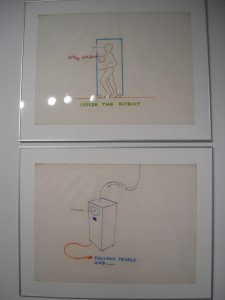

Downey was born and raised in Chile, where he was educated as an architect. He was one of a group of artists, scientists and thinkers who shared a utopian view of the possibilities of machines, and was among the artists whom MIT brought together with engineers and scientists at the Center for Advanced Visual Studies. He worked with robotics and interactive sculpture, and in 1968 exhibited electronic works in Judson Memorial Church and at a Brooklyn Museum/MoMA exhibition organized by Experiments in Art and Technology. Many of his electronic projects involved equipment that interacted with people, responding to human presence, breath, or sounds. In a drawing for a low-tech “robot” which follows people (above), a wooden box is activated by a person standing inside it. He may have been joking.

Downey organized dances and happenings, some of which included closed-circuit video loops. One tape records an action he and Gordon Matta-Clark performed during lunch hours in the area of Wall Street in 1972, offering passers-by a free breath of fresh air, delivered from a tank on a mobile cart. Their comment on the commercialization of natural resources would work equally well today. In 1973 the Everson Museum of Art commissioned the video performance Plato Now: nine performers (including curator, David Ross, and artist Bill Viola) meditated, attempting to produce alpha waves that would trigger an audio recording of Plato’s Republic and Timaeus, as their images were seen by the audience via closed-circuit video. Footage of the performance is in the exhibition, but it is very hard to tell how seriously the participants took either the idea of meditation as a performance, or the possibility of brain waves as a switch (although given the period’s interest in the writings of Jung, Reich, Leary, Castaneda and others, they might have been serious).

The room-sized installation Video Trans Americas (1976-1997) is Downey’s best-known and most ambitious work. It has been installed differently over the years, but as shown at the Bronx it consists of a map of Latin America outlined on the floor and fourteen monitors, each of which shows footage from a trip Downey took from New York to Tierra del Fuego, and a second trip during which he lived with two indigenous groups. Much of the material resembles what any tourist of the times would have seen: a village dance, women weaving, archaeological sites, walking the Nasca lines and inspecting Machu Pichu. Contemporary, urban scenes include a pro-Allende rally in Santiago and visits with locals in Texas. Only a few of the videos have voice-over narratives; in one, the artist initially situates himself as a cultural communicant and activating anthropologist, but later acknowledges he was a pretentious asshole.

The Romantic primitivism and search for origins which the trip enacted is an old one. Downey was searching for his own lineage, the territory of two, connected continents (which his life had straddled) and the most basic forms of community and art. He took the longest road trip possible in the Americas, and admits that he traveled so far to find – himself. While much of Downey’s work always involved large and serious ideas, which were central to his thinking, his refusal to take himself too seriously inserts an irony that was unusual for the time, and anticipates much later art.

Downey made numerous single-channel videos, many of which question the documentary form, particularly the anthropological film, and it’s foundational fiction of a neutral camera. He often includes himself, as in The Laughing Alligator (1979), shot during the seven months that Downey and his family lived with a group of Yanomami. He pointedly never lets us know what is verité, and what is scripted. The light-weight, closed-circuit video equipment enabled him to replay scenes for his subjects to see, and in some instances he offered up the camera, for their use. He clearly wished to rebut anthropological discussion of the Yanomami as fierce, but his own stance as observer/participant is fluid. He participated in rituals which involved psychedelic substances, and created a series of drawings following meditations. The exhibition includes these drawings as well as several made by his hosts, using Downey’s materials.

Downey is always playing with the triangular relationship between the video maker, his subject, and the audience, refusing to claim only one role for himself; he is observer and observed, a manipulated image and a subject with his own agency and voice. In another anthropological-styled video he assumes the role of talk-show host, interviewing a French anthropologist who also lived with the Yanomami. In four later videos from the series The Thinking Eye, Downey investigates the use of mirrors and the illusions of perspective within canonical European painting and architecture. They draw upon his research and readings in literature, psychology, philosophy and art history, and extend his career-long interest in perception, self-perception, and the foundations art-making.

The exhibition is large, and encompasses many more works and ideas than I have been able to address; if you want to see all the videos, it will take more than half a day. It was curated by Valerie Smith and is accompanied by a bi-lingual catalog (Juan Downey; the invisible architect ISBN 978-0-938437-76-5), with essays by Smith and three others, as well as interviews with eighteen artists, curators and friends who knew the artist.

Since March, in a bold move to make the museum truly accessible to its local community, the Bronx Museum of the Arts has eliminated admission charges. It appears to be successful. A staff member told me they’ve seen an increase in families dropping by after school, which I can attest from my visits. The museum also sponsors a variety of activities, including fairs of local craftsmen and programs for teenagers, that are models of community outreach. If the Bronx Museum isn’t on the regular circuit of art lovers, it’s their loss. Getting there is a fast trip on the 4 train, only two stops beyond Manhattan, although on my first visit to the exhibition I was likely the only person exiting the train at 161st St. who wasn’t heading to Yankee Stadium for opening day.