by Dayton Castleman

“So where the hell is Bentonville, Arkansas, anyway?” began the ever-so-subtly titled 2006 Artblog post, “The Hunt for Bentonville.” The article was one of several related to the sale of Thomas Eakins’ “The Gross Clinic” to Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, located just north of the Bentonville town square, and just a few short miles from the headquarters of Walmart, the world’s largest corporation. Bentonville will also be my new home come July, having been drawn there simply by the chance to be a part of making a mark, as an empty canvas of the art world is stretched over the frame of small-town America.

I’d been made aware of the museum by my parents, who live in a small university town nearby, and I’d helped move “The Gross Clinic” when I lived in Philadelphia and worked as an art handler for Atelier Art Services. So I followed the proceedings with great interest, even chiming in here on Artblog as it was all going down. In the end the “Gross Clinic” stayed home in a gritty, come-from-behind Philadelphia-style victory. And while Crystal Bridges may not have succeeded in bringing Philadelphia’s artistic crown jewel within its borders, the aftermath of the uproar still begs the question: where the hell is Bentonville, Arkansas?

I was able to see Crystal Bridges just two months after its opening. Prior to my visit I was kept appraised of the progress at the museum through regular mailings of local newspaper clippings from my parents. When Crystal Bridges opened they sent me pictures of the members’ grand opening of the museum. The picture I remember in particular was John Baldessari’s “Beethoven’s Trumpet (with Ear) Opus #132,” a sculpture of a giant golden ear trumpet emerging from a huge white ear hung in relief on the wall. “Weird,” I thought. But only because it was Crystal Bridges.

Driving up the curving, tree-lined road to the museum, I was completely focused. I was finally at the heart of all the Gross Clinic controversy; the focus of all of the conversation about looting, poaching and pillaging. The first thing I saw was not a Kincade, a Remington, an Eakins, Bierstadt, or Homer, but Roxy Paine’s “Yield,” a giant, venous network of stainless-steel piping conceived at an aggressive diagonal that evokes a barren tree in its wooded setting. Paine’s work is a visually-striking, crowd-pleaser of a first impression, make no mistake, but there are safer crowd-pleasers if your audience is a conservative crowd. I wasn’t cynical about the museum’s quality, mind you, but I was still guarded about how forward-thinking it might be.

The collection is presented chronologically in a series of low, connected pavilions, designed by Israeli architect Moshe Safdie, and built around a large pond fed by Crystal spring. The site itself is a visual treat, with the copper-roofed armadillo-like shells of the museum’s pavilions striking a bold, integrated profile within the lush gorge.

Inside, one of the first works I came to was Eakins’ “Portrait of Professor Benjamin H. Rand,” which the museum did acquire from Jefferson University Hospital in 2007. While not the tour de force that “The Gross Clinic” represents, it is emblematic of the collection’s strength: A broad, solid collection of American art, punctuated at chronological intervals by iconic works that many in the general public will recognize (and anyone who’s taken a decent art history course surely will). It’s a smart curatorial move, as it always leaves a collection highlight just around the corner, including Eakins’ “Rand,” a Charles Wilson Peale portrait of George Washington, Asher Durand’s “Kindred Spirits,” and Norman Rockwell’s “Rosie the Riveter.” (I like what Dave Hickey has to say about Norman Rockwell in Air Guitar: “Most of the artists I have known actually like Normal Rockwell and understand what he is doing. The preachers, professors, social critics, and radical sectarians who hate Rockwell invariably mistake the artist’s profession for their own; they accuse him of imposing norms and passing judgements, which he never does” – from the essay “Shining Hours/Forgiving Rhyme.”)

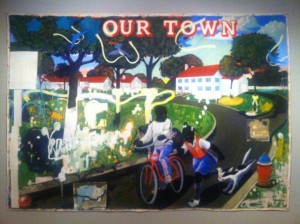

The modern and contemporary collection was a relief to see, with luminaries predictably well represented, but full of solid representative examples of less popularly known contemporary American artists. It is the forward-thinking of the collection in this respect that surprised and delighted me. Kerry James Marshall’s “Our Town,” one of the Chicago-based artist’s most important works, was a nice surprise to see. Another treasure is Jenny Holzer’s “Venice Installation: Gallery D (Second Antechamber),” one element of Holzer’s 1990 pavilion installation at the Venice Biennale, where she was the first woman to represent the United States, and for which she was awarded the prize for best pavilion. I came in knowing that the collection at Crystal Bridges was valuable. I left with the sense that it was important.

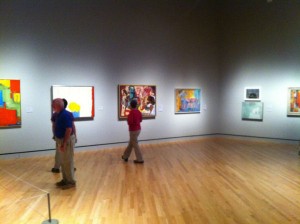

The most glaring bucking of convention was in the lighting and hanging of the modern and contemporary work in the main galleries. With about 80% of the collection currently on display, the works are presented densely, spotlighted in chiaroscuro pools of light and hung on painted walls. This is fine for the earlier works, but the hanging of the modern works (in an effort to contextualize them, I suppose) feels too dense, and the lighting too melodramatic. I’m just not accustomed to seeing abstract expressionist paintings, for example, with so little elbow room. The hanging seems to resist some of the very ideas regarding the object’s autonomy that gave birth to the work, and left me longing for a more spare installation, white walls, and flooded lighting.

I spoke to assistant curator Manuela Well-Off-Man about this and she acknowledged she has similar sentiments, but stressed that the desire at this point in the museum’s life is to show as much of the collection as possible, rightly pointing out the special exhibitions space as an exception, with very nice white-cube gallery spaces clearly designed to remain flexible and accommodating for contemporary work.

Crystal Bridges exudes the confidence and energy that one would expect from a brand new museum, but it still retains the relaxed ethos of a Southern institution. On my first visit I waited for an hour on a chilly but comfortable clear December evening to see James Turrell’s “The Way of Color,” a site-specific circular pavilion set into a green hillside on the museum’s ravine campus, a round oculus in the structure left open to the sky. It was late in the day on a Friday evening and I struck up a conversation with a woman nearby who turned out to be the museum’s deputy director, Sandra Edwards. It felt odd, frankly, to meet a museum executive taking in the art on a chilly, late December evening, but it was refreshing.

A few months later I asked someone with a name tag whether there was anyone that could answer a few questions about the museum. As I sat in the cafe area on a comfortable couch, drinking my latte and gazing at a Claes Oldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen greased-intestine of a stacked alphabet, I was visited by the media communications director, the librarian, and assistant curator Well-Off-Man. I left the museum feeling no doubt that, had I planned ahead, I likely could have spoken to anyone on the museum staff.

Meanwhile in Bentonville:

While Crystal Bridges exceeded my expectations, the eye-opener was Bentonville itself. Downtown Bentonville is situated around a classic Southern town square and boasts a postcard-perfect line-up of small eateries, restaurants, coffee shops, a bike shop, a vanity art gallery, a barber shop, a skating rink in the winter, and of course the Walmart Visitors’ Center and Spark Cafe. Yet beginning to sprout up amidst the home-town storefronts are some real art gems, and signs of the interesting things that are bound to happen when you plop a nearly-half-billion dollar museum in a town of 30,000 people with relatively low cost of living, and already notably-high quality of life.

Tucked into an upstairs space on the square is sUgAR Gallery, the student-run gallery of The University of Arkansas, which is located about 25 miles away in Fayetteville. The gallery is home to a number of undergrad and grad exhibitions. Frankly, I think it’s important to any growing art ecology that there be a place for student work to be seen regularly; a place where you will see both bad art and good art, but that brings with it that energy of fresh blood attempting to carve out a place in the art world.

The most visible new addition to downtown Bentonville, and a harbinger of the entrepreneurial onrush the town seems poised for, is the 21c Museum and Hotel. Bentonville’s incarnation of this innovative boutique hotel is scheduled to open in 2013 (the original is located in Louisville, Kentucky, with another slated to open this year in Cincinnati). Imagine a legitimate museum of contemporary art combined with a hotel and open 24-hours a day.

The Louisville location was completely surprising on my first visit, with several, large, dedicated galleries and exhibition spaces that include works in the museum’s permanent collection as well as special exhibitions As the name suggests, the museum is focused entirely on 21st-century work, and I enjoyed seeing Philadelphia represented in Louisville with a site-specific, day-glo Virgil Marti wallpaper installation. This fall I was able to see Cuba Now, an incredible show of contemporary Cuban artists, and if the quality of that show is any indicator of how high 21c sets the bar, it means viewers have a lot to look forward to in their newer locations.

Following on the heels of the 21c Museum and Hotel will be a 2,200-seat performing arts center, an expansion of the Walton Arts Center in Fayetteville. The dance and music line-ups of the Fayetteville location closely resemble the offerings of other university-situated theaters such as Penn’s Annenberg (dance companies such as Momix and Mark Morris, and music such as Yo Yo Ma and Joshua Bell), but you can catch Hank Williams Jr. too.

Significant to the atmosphere I sensed in Bentonville are the people the town is attracting. In a few short days I met twenty- and thirty-somethings that have relocated to Bentonville from SoCal, Austin, Minneapolis, and Colorado. In casual conversations with a variety of people, the optimism about Bentonville’s future potential as a destination for artists, not just art tourists or scholars of American art, could be clearly sensed. Put as plainly as possible, when this much money and this much art are to be found in a healthy small town with a cost of living and available resources and work space that would make any mega-urbanite artist drool, then even moving to Arkansas can seem like a pretty tempting idea.

Philadelphians can enjoy knowing that even if things had turned out differently, “The Gross Clinic” would have had a good home away from home.

—Dayton Castleman is an artist and curator living in Arkansas.