Commotion is a six-month project directed by John J. H. Phillips for University of the Arts (U Arts). Funded under the Philadelphia Redevelopment Authority (RDA), it involved a course for U Arts students, seven professional artists in various art forms (including writing, dance and theater), workshops with residents of Grays Ferry, Point Breeze, and South of South Street, two artists as workshop leaders and a large number of technical staff. The funding for Commotion was generated by PECO‘s construction of a power station in Grays Ferry; following legislation in 1959, any private developer who obtains property through the RDA must devote 1% of the construction budget to art. Those funds can be used in various ways to bring art to the community, but this was the first time it was devoted to temporary, community projects. A step into the dark.

Commotion culminated in a festival running June 16 – 30, to present the results in a series of free activities and events in South Philadelphia; from what I was able to attend during the first week, before I left town, it proved worth the risk, a successful undertaking according to multiple standards. This can certainly be credited to selecting Phillips to direct it, his choice of highly-competent fellow artists, and the free hand that all were given. I came away from the festival with a book, a cd, and memories of new places and people, good food, a lot of creative activity, enthusiastic students and one particularly stunning performance.

In the work for which he is best known, Phillips collaborates with Caroline Healy on site-specific multimedia installations that are a hybrid of sculpture, video, and sound. They created a terrific installation at Diston Saw Works as part of Hidden City Philadelphia, which I wrote about on June 17, 2009; it was as good as any site-specific project I’ve seen, and the artists put a lot of effort into relationships with the Diston workers and neighbors. Phillips chose the artists participating in Commotion based, in part, on their experience teaching and interacting with the general public. This is more and more demanded from artists, but it’s hardly part of the traditional job description. The Commotion artists are: playwrite Ed Schockley, a Point Breeze native and pioneer in community engagement theater; Jebney Lewis, a musician and visual artist trained in technical theater production; choreographer Niki Cousineau and designer Jorge Cousineau, who, as Subcircle, specialize in activating a variety of spaces through a combination of installation, dance and dramatic elements; Team Sunshine Productions, a collaborative that creates original physical theater grounded in everyday life; and Tim Fitts, a writer and teacher who also works in photography.

Many of the artists employed the U Arts students and each involved the community in his own way, without Phillips’ direction, although I imagine he was regularly contacted for technical help; multiple artist projects don’tjust come together on their own. The Commotion project was remarkably free from a unified rhetorical or theoretical position which sometimes accompanies both public art and community-based activities. Phillips told me his priority was that good art should come out of the project rather than a feel-good, community activity. It did. And quite a bit of community involvement as well as some remarkable pedagogy; this experience will certainly be among the more memorable of the students’ courses .

Fitts lead workshops at Zion Hill Memorial Baptist Church and the William A. Barrett Nabuurs Center where he photographed personally-significant objects that the participants had with them and used some of the photographs in a silk-screening workshop(above) conducted with each group. All of this was incorporated in a book, 46-45 Verandering, using some of the workshop-generated imagery as well as Fitts’ photographs (many are details) of the surrounding neighborhood, where derelict public fixtures and vacant property abut very modest, old housing and the occasional new, publicly-funded construction. Fitts describes his interaction with the neighborhood and its residents in a short text, but the title is a mystery to me.

The community participation with Commotion‘s dance component was as guests at performances by Subcircle and Team Sunshine, with a meal served in between and ice cream as a finale. They were held at the 1842 Shilo Baptist Church, and the chance to see rooms beyond the sanctuary of the neo-Gothic structure was worth the trip – even on one of the hottest evenings of the year. Subcircle seated us in the church balcony opposite a large screen where we saw a live feed of our own presence layered over photographs of what I assume were congregants from earlier times. Then they lead us up stairs, around corners and through a series of intriguing spaces where performers in vaguely 1920s dress interacted with the rooms, props, each other, and occasionally with us, miming a story we were never quite privy to. Still, their purposeful and coordinated actions and the movement through the rooms, appointed variously with vintage items, was an intriguing if puzzling first course. Next we were served a perfect summer meal at tables small enough to generate conversation; the people I met over dinner were either related to the artists or art followers from outside the neighborhood (we all had to pre-register for the free event). The next stop was a raw space in which Team Sunshine performed a humorous but slightly protracted piece, essentially a mimed story with captions and a consciously, low-tech set constructed largely of cardboard and tape. I enjoy that sort of theater, but couldn’t discern any relationship with the setting; perhaps that wasn’t the point. The event will be repeated on June 27 and 28, but I understand it is sold out.

The Greatest Life that Never Was is a new play that Ed Schockley wrote, based on stories told by South Philadelphia residents. He conducted neighborhood workshops on acting, storytelling and performance, and readings of the play, which was performed with professional actors on June 23rd and 24th at the Mitchum-Wilson Funeral Home, chosen because of the play’s subject of lives cut short. The stories may have come from the community, but the storytelling was Schockleys, and he’s a master. It was a work in progress that at its high points was some of the best theater I’ve seen in Philadelphia. The actors thoroughly inhabited their roles, and the connection with the audience was palpable. Schockley is still developing the script, and hopes to arrange future performances.

Commotion‘s sound component included several workshops on recording ambient sound and a virtual sound art project, Sound Places, by Bowerbird that will run during the festival, with compositions created from sounds recorded at a dozen locations within the Commotion project boundaries. They are intended to be accessed via smartphones (or downloaded from the web or used with an iPod) at those same locations. I wasn’t able to experience them in situ, but did listen to the pieces on a cd as I sat at home. They contain a wonderful range, from traditionally musical to electronic-generated sounds and ambient, urban noises. I find the idea of a sound piece (may I call it music?) written to be heard at a specific location a delightful one. Site-specific sound. I wonder if it will induce any of the audience to take off their headphones on the next walk around Philadelphia and try living to a live, as opposed to a prerecorded soundtrack.

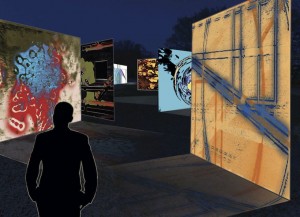

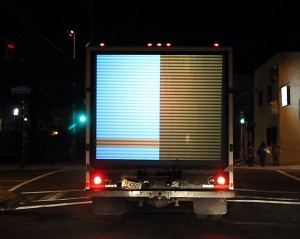

The remaining projects include the debut of a huge sculpture created with theparticipation of many school groups, directed by Jebney Lewis (above), and Phillips‘ large-scale, interactive sound and video art installation (both can be seen on on June 30), and his other project: a mobile, video-art wagon (above), that Phillips created with help from neighborhood youth, who attended classes at Scribe Video Center; it will make periodic, night-time tours of the neighborhood. The June 30 event is billed as a community block party featuring live music from local musicians, a gallery of artwork from neighborhood artists, kids’ arts and crafts, food, and an outdoor movie suitable for all ages; all the events are described on Commotion‘s website.

Commissioned artwork always involves risk; the work may turn out to be disappointing. For art commissioned with public funds, it’s more likely than not that someone in the community will object to it and invoke the taxpayer’s right to voice an opinion. But commissioning an undefined project that will leave no permanent object behind is a far greater risk. Having worked for a percent for art program, I very much favor temporary projects. They don’t require on-going care, and artwork sited outdoors or in highly-trafficked locations demands constant upkeep, and look dreadful if neglected. Temporary projects are often more suitable for the budgets available, whereas major permanent art requires budgets that resemble construction budgets rather than art budgets. But I favor temporary work primarily because the artists can be more adventuresome, since public objections can be mollified by the understanding that within a finite period, the work will be gone.

It’s not easy to determine the audience for a project such as Commotion: local residents, the U Arts students, the greater Philadelphia cultural community, the participating artists, PECO or the RDA. Commotion offered something for each of them, which is quite an achievement indeed.