Julie M. Johnson. The Memory Factory; The Forgotten Women Artists of Vienna 1900 (West Lafayette, IN: Purdue University Press, 2012) ISBN 978-1-55753-613-6

It’s remarkable that recent scholarship can force significant reconsideration of an artistic culture as well-studied as that of Vienna around 1900, but that’s what Julie M. Johnson’s work has done. As such, it will be required reading for anyone interested in Vienna’s turn-of-the-century art and art institutions, particularly the schools and the artists’ associations and unions – which functioned much as today’s artists’ collectives and artist-run spaces. It is also an important contribution to women’s studies and to the historiography of art, for it documents a group of women artists who were active in Vienna’s art world around 1900 but were entirely written out of later historical accounts.

Based upon intensive archival research, Johnson demonstrates that, unlike the better-studied situation in Paris, women in Vienna had access to art education, and while they were barred from official membership in the major artists’ unions, that didn’t keep those same groups from exhibiting their work. In fact, women participated in the mainstream modernist art movements in Vienna. The city not only trained local women, but attracted women from Russia, Germany and the provinces. They had successful careers, exhibiting across Europe; their work was acquired by the emperor, the state, and private collectors; they received public commissions, and exhibited in major exhibitions at the Kunstlerhaus and the Seccession, commercial galleries and alternative venues.

Tina Blau (1845-1916) introduced Impressionist painting to Vienna and became financially successful through her work. Her paintings were purchased by the Emperor and shown in solo exhibitions in Vienna and across Germany. She had a studio in a government-owned building in the Prater, Vienna’s popular public park, which became the subject of many of her best-known works. In 1882 when the French Minister of Art, Antonin Proust, visited Vienna and saw her work, he encouraged Blau to submit a painting to the Paris Salon; she did, and won an honorable mention. Blau was Jewish, and in 1938 her work was removed from public collection galleries and a street dedicated to her was re-named; for many decades she was unmentioned in histories of the city’s art. Her first solo exhibition in post WWII Vienna was in 1996, at the Jewish Museum.

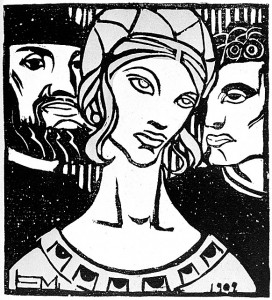

Elena Luksch-Makowsky (1878-1967) exhibited with the Secession and participated with the Wiener Werkstätte. Access to Secession activities was certainly easier because her husband, Richard Luksch, was a member; she functioned largely as an unofficial member (although without voting rights), exhibited in important exhibitions developed around the idea of Raumkunst (literally spacial art – an integration of art with interior architecture and design that was at the center of Secession activities during the first years of the Twentieth Century) and contributed all of the illustrations to one issue of its publication, Ver Sacrum. She also produced a ceramic relief for the facade of the Wiener Burgertheater (Vienna People’s Theater) and was known for her graphic work and book illustrations, which drew on her Russian background. She, too, was largely written out of the histories of the period and there is no monograph on her work.

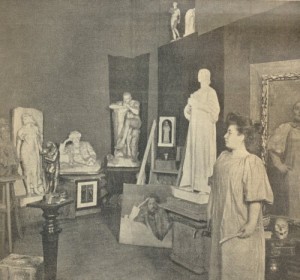

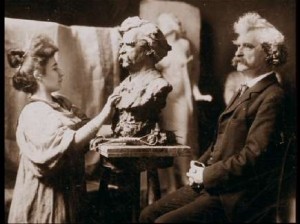

Theresa Ries (1874-1956) was kicked out of the Moscow Academy of Art for talking back to a professor. She moved to Vienna where the first exhibition of her sculpture attracted the attention of the Emperor and brought Ries overnight fame at the age of twenty-one. The work depicted a young, mischievous witch, nude and seated on the ground as she cuts her toe-nails. Klimt asked her to exhibit with the Secessionists and she sent work to the 1900 Paris World’s Fair and the 1911 World’s Fair in Rome, where she was invited by both Russia and Austria. The Prince of Lichtenstein gave Ries a grand suite of rooms next to his picture gallery to use as her studio, which she inaugurated with a ten-year survey of her work. Ries was effective at self-promotion – the critic Karl Kraus complained that her exhibitions received too much publicity – and framed her own story by publishing a memoir in 1928. Her studio was Aryanized in 1938, after which she worked elsewhere in Vienna until 1942, when she left for good. Post-war Vienna ignored Ries’ contribution, as it did with so many of its Jewish population. Many of the women artists in Vienna were Jewish, and the perception that certain artists’ associations and schools were primarily Jewish insured their obliteration both as institutions and as part of the historical record.

All recent writing on these artists has been in German, as Johnson’s extensive citations reveal. Her research yielded a more extensive analysis of Vienna’s complex institutional art structures than has previously been published anywhere, and will certainly insure the book’s importance. Johnson looked at archives of the art schools and artists’ unions, lists of work exhibited in art association spaces and at private dealers, and contemporaneous critical, journalistic and scholarly writing.

One distinctive aspect of art in Vienna was the significance of artists’ unions and associations, which provided most of Vienna’s spaces for art exhibitions. They showed their members’ work (and sometimes that of non-members), took a smaller commission on sales than did dealers, offered pensions, made arrangements in connection with state purchases and were a channel for distributing state funds to artists. Of them, only the Secession has received widespread attention. It was one of three large groups which regularly received state support (the others were the Kunstlerhaus and Hagenbund; the Austrian state understood that even if it didn’t favor the art, promoting a vibrant artistic culture was good for international business and politics. None of them allowed women as voting members; all three, however, exhibited work by women. But there were many other associations, some integrated, others exclusively for women. Johnson’s research enables a comparison of Vienna’s artists’ associations with the many, current artists’ collectives and artist-run space that have characterized the U.S. art world for the past several decades. These share many of the functions of Vienna’s associations: providing curatorial and exhibition venues for artists working outside the commercial art world, offering locations for theoretical and practical discussions, promoting a particular artistic view and publishing artists’ writing. And like Vienna’s unions and associations, contemporary artists’ groups are able to apply for funding (private, rarely state funding) that would not be available to individual artists, for exhibitions and other projects.

Johnson devotes serious attention to critical discussions about women artists and the problem of their place in the established story of patrilineal artistic development. She is equally interested in the erasure of their history after World War II, and makes use of recent scholarship about memory to analyze how a group of artists so broadly involved with Vienna’s artistic life around 1900 could be forgotten. History is the product of information which is repeated. The record of Vienna’s Jewish artists was intentionally suppressed; for the non-Jewish women, a variety of circumstances broke the chain of repetition (exhibition, reproductions, writing) from which art history is made. A number of the resurrected reputations resulted from efforts of the artists’ families, who produced books and exhibitions; others resulted from work by Austrian scholars, beginning in the 1990s.

A chapter is devoted to the exhibition organized by the Association of Women Artists in Austria (VBKO), which received state funding in 1908, The Art of Women, which included 300 works by Renaissance to contemporary artists. Held in the Secession (the book includes an exhibition plan and several installation photographs), it was organized by two VBKO members who had six months to find work in museums across Europe. It is especially surprising to read about this exhibition in light of the major impact of Women Artists, 1550-1950, an exhibition half that size which Linda Nochlin and Ann Sutherland Harris organized in 1976. The art historians spent five years researching essentially the same material as had the women in 1908, and acknowledged that much of it was new to them. A history certainly interrupted.

Purdue University Press is to be congratulated for publishing this book through its series on Central European Studies. It is extensively illustrated with works by the women artists and their male colleagues as well as with many valuable views of exhibition installations, showing the women’s work in situ. It is unfortunate, given the unavailability of much of this material, that the format could not have been larger and the illustrations better-printed, although some suffer from the necessity of being reproductions of reproductions – that being all that remains of missing works. It is hard to raise funds for a book about artworks that are not well-represented in major museums nor likely to have a significant commercial market. But it tells an important story about aspects of art and its history which are still current.