by Susan Hagen

Art is the only twin life has. –Charles Olson

Art goes beyond economics. –Bill Bollinger

Hoses, rope, hardware, fencing, wheelbarrows, 55-gallon drums, water. These are the components of Bill Bollinger’s sculptures, now featured in a retrospective exhibition at the Sculpture Center in Long Island City, New York (until July 30). Always using the most direct approach, Bollinger — a seminal Post-minimalist — applied almost-invisible interventions and material-appropriate craftsmanship to ordinary materials and objects to create moments of luminous poetic sensitivity. His sculptures address the fundamentals of reality: orientation, the laws of physics, connections between things, and missed connections. As remarkable as it is from an artistic perspective, this show is also personally meaningful for me. Bollinger was my sculpture professor when I was a student at the Minneapolis College of Art and Design.

Bill Bollinger (1939-1988) was born in Brooklyn, New York and studied aeronautical engineering at Brown University before moving to New York to pursue a career as an artist in 1961. Bollinger had a well-established art career by the late 1960s but left New York in the mid-1970s to regroup financially and take care of his young son. He continued working and exploring new directions but was never able to re-engage in the art world, despite attempts in subsequent years. Always confident of his artistic vision and abilities, he nonetheless became disillusioned at the end of his life. Because he saw his works as temporary, transitory objects few of Bollinger’s artworks survive, and those that do are mainly owned by European museums and collections. He cared little for making art that would “last” and even less about maintaining a “look.” In addition, Bollinger’s personal problems, frequent relocations, and premature death due to alcohol abuse created problems with his estate, and many of his works have been lost.

Bollinger’s achievements were forgotten by the art world for decades, but in recent years a few determined individuals brought renewed attention to his work and made this exhibition possible. In 2000, Wade Saunders wrote a compelling article for Art in America about his fascination with Bollinger’s work and his quest to learn more about the artist. Christiane Meyer-Stoll’s excellent curatorial work on the retrospective, which toured three venues in Europe prior to its presentation in New York, was aided by input from Rolf Ricke. Ricke’s gallery in Cologne represented Bollinger’s work from 1968-71. Mary Ceruti, director of the Sculptor Center, provided a North American venue for the show.

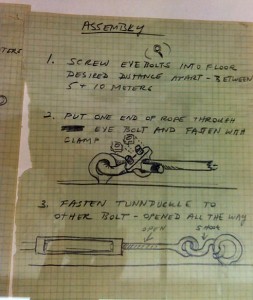

The retrospective highlights a cohesive moment in the career of an artist who was curious, uncompromising and difficult to categorize. Throughout his career, Bollinger created paintings, drawings, installations, and sculpture in a huge variety of media and styles, as well as performances, films, photographs and poetry. The show includes a variety of archival materials, drawings, and sculptures (original works, as well as reconstructions). Bollinger believed his work could be made by others, as long as they followed his exact specifications, and this provided the moral basis for the reconstructions created for the exhibition. The show would not have been possible without the drawings, letters and photographs in the Ricke archive, which was acquired jointly by three European museums in 2006. These materials build a detailed and complex picture of this artist and his work, as well as provide the precise drawings and directions for the reconstructions.

All of the sculptures in the show dwell on elemental tensions and relationships, and many contain water. Boston Common is a cluster of 55-gallon drums filled with water, with numerous rubber hoses in relaxed loops connecting them. Watching it, like many of Bollinger’s works, for any length of time produces a quietly troubling awareness of the absurdity of human enterprise. Several of Bollinger’s earliest 3-dimensional works, the “Channel Pieces” from the mid-60s, which Bollinger thought of as paintings, are mounted very high on walls and in corners. Other pieces lie passively on the floor, as if dropped. The sublime installation “Graphite Piece, 1969 (2011)” – produced using thrown and smeared graphite powder – invokes the tradition of Romantic landscape painting with a vast central field of velvety, black graphite, while the hand and footprints around its edges read as awkwardly temporal human gestures. The show also features dozens of Bollinger’s drawings. Many suggest plotted and pieced landscapes, weather conditions, or lusciously atmospheric horizons. Other drawings have a practical purpose and provide information.

An excellent catalogue, the first thorough monograph on Bollinger, accompanies the exhibition. It documents and records hundreds of Bollinger’s works, creating a fascinating picture of the depth and range of his oeuvre. The works include outdoor pieces, for example, his “Log Pieces,” logs drifting or anchored in rivers, and “Stone, 1969,” the temporary installation of a stone removed from the World Trade Tower excavation in Anti-Illusion: Procedures/Materials at the Whitney. Also included are Bollinger’s photographs of his studio, snow fences, and the sea, taken when he crossed the Atlantic in a freighter. Biographical information, essays and remembrances of the artist also appear in the book.

After seeing this exhibition, I looked back through my sketchbooks from the years I studied with Bollinger. He was the source of many ideas I take for granted as an artist: “Do what you need to do, not what you think you ought to do; there is a progression from not being able to explain, to being able to explain, and then back to not being able to explain again; sculpture should be about who you are and about where you are; be American; study the particulars;” and much more. Bollinger was a down-to-earth but completely rigorous intellectual, and his enthusiasm for American writer and poets, such as Charles Olson, William Carlos Williams, and Herman Melville, was infectious. He believed that poetry and sculpture were closely related and liked how poetry, read aloud, could fill a space just like sculpture. On the other hand, he told his students that he wanted to be called a “plumber, not a sculptor.”

When Bollinger left Minneapolis in the late 1970s he gave away the contents of his studio to his friends and students. I still have a few of his books.

Susan Hagen is a Philadelphia sculptor who has exhibited her work at museums and galleries across the US, and written hundreds of articles about art for the Philadelphia City Paper, Woodwork Magazine, Hand Papermaking and other publications. Her work is represented by the Schmidt Dean Gallery in Philadelphia.