The train from Karlsruhe to Kassel took a little over 2 hours. Not only is Kassel north but it is higher elevation. We passed from flatlands to rolling hills and smallish mountains dotted with herds of cows, sheep and goats. When we arrived, the air was cooler than the Mediterranean soup we’d experienced in Karlsruhe.

We checked into Villa Zandoli, a cute bed and breakfast in walking distance of Documenta’s hub of activities. (Thank you Andrea for that tip!) And while we didn’t see much of the town, we noticed its difference from Karlsruhe. As more of a tourist destination, there were street musicians–good ones. The main shopping street seemed to have many of the same international stores as Karlsruhe (H&M, Starbucks) but the layout of the street was more upscale somehow. And bike riding, well it wasn’t as much in evidence.

Documenta 13 involves 300 participants, including scholars, critics, a team of physicists, performers, musicians and of course artists. In this once-ever-five-year festival that lasts 100 days, there are reading groups, lectures and seminars, films and even a writers residency. It seems more like a small moveable university to serve the long term residents than a place that is a notch on the belt of the art tourist. It would be great to spend a summer here and partake of all the offerings.

KARLSAUE PARK

With eight main venues and numerous projects sprawling through the big park nearby and in various historic locations we saw the tip of the iceberg before we had to get back to Karlsruhe. Even before reading the material about what was on view, I got the sense that Documenta 13’s theme was social practice and the possible ways artists are commenting on world issues and perhaps even doing something about them. We didn’t see a lot of really great objects, and what we did see kind of beat you over the head with its message. But some of it was enjoyable and memorable. Here below is a picture post with some commentary.

The park serves as an experimental zone for artists who create new works in small huts throughout. It’s a huge place and Giuseppe Penone’s bronze tree holding aloft a large boulder makes a dramatic entrance to the park. We saw one installation, by Robin Kahn and The National Union of Women from the Western Sahara. Kahn had brought some women from the National Union to Kassel for part of this performance/display piece. What we saw was a tent in which we were invited to sit, drink tea and eat kabobs, and talk. Panels set up near the tent explained more about the National Union and the plight of women in the Western Sahara.

OTTONEUM

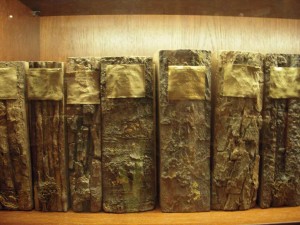

Pennsylvania artist Mark Dion created a beautiful wood cabinet in the the natural history museum to house the museum’s collection of peculiar tree books, called the Schildbach Xylotheque (1771-1779).

These are “books” in looks only, made from bark of the individual tree catalogued in the collection. Each book is actually a box — a kind of Joseph Cornell-box with a jumble of natural objects that relate to the tree.

Oddly, the beautiful cabinet housing this strange collection of faux books works. It falls away and lets you absorb the weird wonder it contains without being a showboat of its own.

FRIDERICIANUM

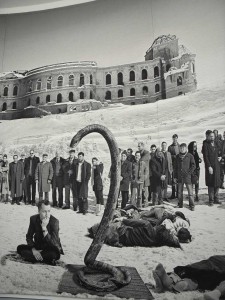

Documenta 13 weaves together past and present objects as it mixes art and science into one big universal melange of ideas about humans, the history of war, and the idea of knowledge and information in our info-saturated world.

Thus in the Fridericianum, the venue that is the central statement of the show, you see tapestries from the 1930s by Hannah Ryggen that chronicle the rise of Naziism, and a tapestry from today by Goshka Macuga — a weirdly satisfying piece of Photoshopped surrealism — with content about the war-fraught Middle East.

I have to believe that it’s because this festival has war on its mind that there is a physics classroom in the show. Physics has played an important role in both the good and the bad parts of human history (from figuring out how things work to making bombs). And the blackboards and young physicists taking people through equations (in German – go with a translator if you’re interested), were so earnest that it almost felt like this was Documenta doing a ritual cleansing of physics for its bomb-making past.

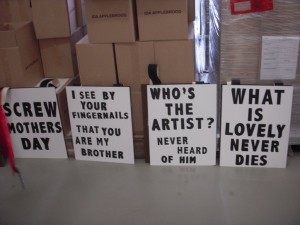

Meanwhile, Ida Applebroog’s punchy installation with thousands of angry posters as giveaways was a complete high point. The lady — can we call her the mother of the Occupy movement? — is great. All her righteous anger, available to all in all its varieties made for perfect mementoes of this political Documenta.

The best objects that I saw were Kader Attia’s carved deformed heads displayed in an open storage unit, looking like part of a Mutter Museum collection. “Repair From Occident to Extra-Occidental Cultures” apparently depicts facial wounds of soldiers in World War I.

The last things we saw were at the old Kassel Hauptbahnhof — Janet Cardiff’s video walk through the train station, and Susan Phillipsz’ sound piece at the far end of one of the train platforms. Both works cued off the train station’s role as a site for deporting Jews to the death camps in World War II. And neither work was visceral enough or connected with the subject enough to make a strong statement.

The Cardiff, which had a Fellini-esque musical component — you followed a tuba player for part of your walk — ended with an abstract dance in the Pina Bausch tradition (dancers falling into and out of each other’s embrace). The dance, while lyrical, felt un-Cardiff-like and tacked on. I would have preferred more of Cardiff’s strange musings about life, love, death and what the Holocaust really did to us as a human race, than to watch the dance, on the tiny iPod touch screen.

More pictures at Flickr. And coming next, my last Europe post for a while –about our weekend in Paris.