Walk into Laurence De Leersnyder’s studio in Saint Denis, the teeming suburb north of Paris, and you’ll think that you have stumbled onto a missile silo workshop. The “missiles” are encased in half-open boxes. Some are lying horizontally while others are upright. They appear to be made of dirt. Though asymmetric and rough surfaced the partially concealed cones are redolent with menace. De Leersnyder has hit a nerve. The French state used to test submarine engines on the site of her studio.

About three years ago in these columns I reviewed a female Columbian artist Juliana Cerqueira Leite who had taken a block of clay and put it on wooden legs. She then burrowed up and into it. At the zenith of her trajectory she arced into a downward trajectory and touched the wall of her entry into the block thus completing a circle. The carrier of a womb digging a womb accomplished an intimacy with her material the likes of which no male could ever achieve. Leite went back upstream as if sniffing out her origins, our origins. I always wondered if she hadn’t passed out or just gone to sleep while in there but she wasn’t giving interviews.

De Leersnyder is quite the opposite. She follows gravity and works her forms downward. “I have yet to break through but continue to dig” she says. De Leersnyder is aerian. She burrows to the sky. To achieve this her method consists of reversing depth, of digging deeper in order to go higher. This is opposed to Brancusi, for example, who aspired upwards by working upwards. Both of these female artists illustrate that all human endeavour boils down to shifting earth, and they do the work themselves but in a way that doesn’t defy gravity but, rather, accepts it.

So for De Leersnyder the deeper she goes the higher she goes and yet she has decided to work within the proportions of her own body. Her biggest work hardly exceeds her height.

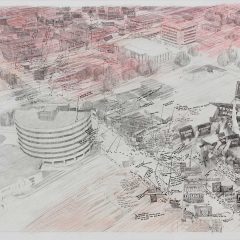

In the gallery of her latest show, La Dame de Byblos, ( til July 28 at Galerie Laurent Mueller) De Leersnyder’s silos are cracked open and the resulting verticals are each a witty combination of immovable pillars capped by a ghostly form in Rodinesque movement. The earthen gown seems to be weightless and the ghostly form moves before our eyes. Though somewhat amorphous, this form is complete because it doesn’t aspire to another state and already contains its eroded future.

Of course the problematics of the earth/pedestal/sculpture relationship are fully evident here. The pedestal acts as a baton that the artist is twirling. On each end is mind and matter, one element of which predominates in its current orientation. Twirl the pedestal 180˚ and what would you see?

An electric motor comes to mind. It spins between magnetic poles propulsed by alternating attraction and repulsion. We know that there really isn’t any distinction to be made between the earth, the pedestal and the sculpture but rather that we must acknowledge each element’s current state and role in the perpetual rise and fall of our material world.

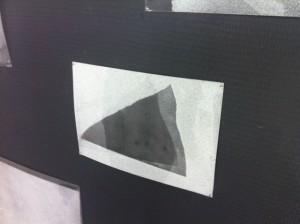

Throughout De Leersnyder’s studio we see fragments of plaster and dried expanded joint filler protuberances shaped all at the limits of their expansiveness and their skins and their molds. Everything is bound by a comfortable limit. And then there is the dust. Dust falls where it will. It knows no bounds. De Leersnyder lets the dust of her studio settle on and around her work fragments like a time machine drapery. Sometime later she lifts the fragments up and away to reveal prints like x rays (dust ray?).

Some of this is captured on glass which is then exhibited like specimens in a Natural History Museum. Some is caught on paper. The resulting negative/positive drawings speak of weight and closeness: a moment, (and not a space because there was no room bettween the side of the fragment and the table or paper it lay on) a pressure of material against material. Still, until a window is left open in a storm or the cleaner comes to the house. . .

The dust reminds us of Duchamp. Men do not vacuum. Is that the Darwinian fact that enabled the Duchamp dust pieces to exist? Is D shaking the nurturing of a society that still has women doing most of the housework? La Dame de Byblos, busy at turning out terrestiel ghost phalluses and ghost drawings, turgidifying the earth and exciting the spectator, inverts the earth and thereby reverse gender, always careful to not strangle the alligator.