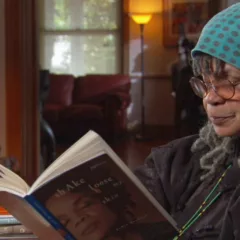

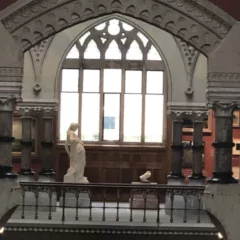

I visited Anne Minich at her home/studio Aug. 3. Anne, who is 78, has been in and out of chemotherapy for the last year, but she is an energizer bunny nonetheless, creating work, organizing an exhibit, “Transformations” at the Cathedral in West Philadelphia (that opens Sept 1) and generously hosting visits from friends and family. “I’m using cancer as a positive thing to move forward,” she told me, in her usual upbeat, no-nonsense way of speaking.

My previous studio visit with Anne, in 2004 (wow, so long ago!) introduced me to an artist who is deeply spiritual and whose work is full of the love of materials. In my Philly Weekly review of her solo show at the Cathedral in 2004, I compared her to Tom Chimes. something I still firmly believe.

“Her symbolist works, restrained and elegant and tinged with sadness, remind me of Philadelphia’s other great symbolist artist Thomas Chimes. Chimes’ works have a literary obsession (the symbolist poets are his muses), and Minich works from a spiritual and personal perspective, but both artists are big-picture thinkers who make haunting works that take a stab at the meaning of life.”

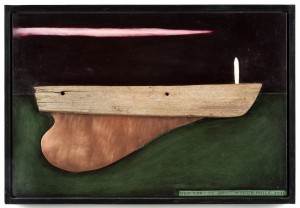

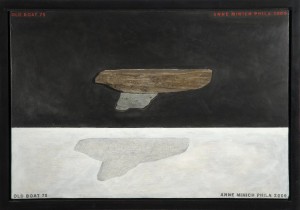

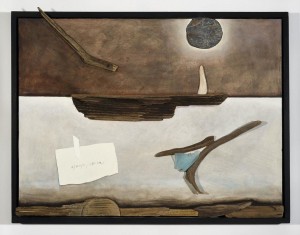

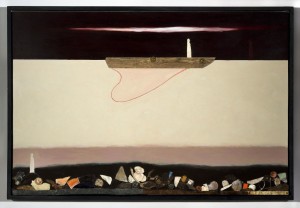

What I saw in this visit is completely in keeping with what I saw in 2004 — gorgeous, spare, iconic works, with a restrained pallete and sly additions of found natural objects (driftwood and stones from beaches in Maine). This time the beautifully-crafted works involve a boat as the main character and symbol, instead of a head or airplane.

There’s some Arnold Bocklin Isle of the Dead in this work, acknowledged by Anne, who said she saw Bocklin’s painting at the Met when she was 12 and was transfixed. “I’m in the last quadrant of my life…I am aware that death follows the last quadrant, she said.

A little background

Anne is from West Chester, PA, and she went to PAFA from 1954-55 when she was 19 (as context, Louis Sloan was an Academy student then too, she said). Anne’s father, a high-end real estate agent, was very supportive of her art from an early age and took her to museums. “He thought I would be the second Mary Casatt…I thought I’d be the first Anne Minich,” she said.

She left PAFA to get married in 1955 (she married an Episcopal seminarian, from whom she is long-divorced, and has a son and a daughter from the marriage). She came back to art at age 35, but when she began making art again, she lacked self-confidence, which she chalks up to a comment made to her by a PAFA teacher who said that she’d never amount to anything if she left school. That horrible bit of negativity stuck with her for a long time.

But, in spite of all, Anne is a beam of positivism. Apart from being upbeat and forward looking in the face of cancer, last year, on June 6, 2011, at 1:30 pm her car was hit by an oncoming car on the Cross Bronx Expressway causing her vehicle to flip over. She was protected by her seatbelt, but hung upside down for what must have seemed like ages before she could be extracted from the car. She was not injured badly (the car didn’t catch on fire but was totalled). The memory of that accident, seared in her brain, is the basis of a relatively uproarious (for Anne) painting, Old Boat 77, which bears the date and time of the accident.

Like many women artists, Anne didn’t have the career tools to put herself forward or the stong hand of a mentor to help her. She doesn’t have a gallery in Philadelphia in spite of the fact that she’s had a lot of success, with a solo show at the Painted Bride, a two-person show at PAFA’s Morris Gallery, a featured spot in the group exhibit, Made in Philadelphia 7 at ICA in 1987. In 1994, she won one of the first Leeway fellowships. Linda Lee Alter (who founded the Leeway Foundation) collected her work, and when in 2010, Alter gave 400 pieces to PAFA, Anne Minnich’s work was included in the gift. An exhibit from the Alter collection goes on display at the Academy this November.

Anne in the studio

Anne makes all the supports for her work herself. She works with birch plywood. She taught herself carpentry a long time ago to do this. When I asked about whether it wouldn’t be better to job that out to someone else, she demurred, saying “It wouldn’t be the same if someone made it for me.”

Also, it’s part of her process. Anne doesn’t sketch out her ideas before painting them. She works directly. “That’s why I do so much revising,” she said. “I have no problem revising, changing the size of things…its my process. I’m not big on planning — it’s very limiting in many ways.”

She’s been making what she calls “late night drawings,” since the 1970s. These are drawings of nude men and women, some explicitly sexual. Some of of them have been collected. Many of the figures are partly-covered with what the artist calls “transparencies,” cloth-like veils, sometimes in pink, that float around or wrap the body. Anne calls the drawings humorous, but what they are to my eye is more than humorous. They are incredibly delicate and yet frank depictions of human sexuality.

On a final note, I am sorry to report that Anne fell and broke her hip while walking to a chemo session recently. A clean break allowed the doctors to put in pins, and Anne is recovering well in rehab, which she hopes to be out of asap so she can get back to what she loves — making art. What she’s really itching to get into next is a nude self-portrait in graphite, based on photos she had taken,after her cancer diagnosis and dropping 30 pounds. It should be a stunning drawing when it’s done. Anne will also be making two small drawings for the Dear Fleisher benefit show, Sunday Nov. 4 at Fleisher Art Memorial.