Oliver Herring, TASK

Oliver Herring is generous through and through. Generous in his art and generous with this book. It is a history of the series of events he organized in a format called TASK at more than thirty sites since 2002. More than that, it is also a recipe book for how to organize an event of your own. TASK, according to Herring, is an improvisational event with a simple structure and very few rules. It is a format for bringing people together, breaking down their self-consciousness and stimulating creativity. Each TASK begins with a venue, uses a lot of craft materials (including re-purposable refuse) and a group of participants invited by the organizers; sometimes they are members of an organization, many timesthe general public is invited, via the usual means of spreading the word: posters, e-mails, Facebook, Twitter, etc. The tasks performed at each TASK event are entirely generated by the participants, so the tenor of each event is unique.

Herring’s first few TASK projects were executed at a Masonic temple in London under the auspices of Rhodes+Mann Gallery, the École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts, Paris, a former bank in Lake Worth, Florida in connection with the ICA, Palm Beach, the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, D.C. and FLUXspace, an artists’ collective in Philadelphia. This diversity of venues characterizes the entire list; someone on Herrings TASK website is looking into organizing TASK on Second Life.

Herring describes that TASK originated in his own increasingly-collaborative art, made with ever larger and more and more random groups of people whom he found via bulletin boards, the web, and word of mouth. The project grew out of Herring’s curiosity about other people and his willingness both to trust them, and to fail, all in relatively public situations, but with few consequences for the participant (but possible implications for the artist). He has not allowed his ego to restrict his creativity. Oliver Herring is brave.

The book includes case studies by Kristen Heilman, the curator at the Hirshhorn who invited Herring to the museum and Kendra Paitz, curator at the University Galleries, Illinois State University who worked with Herring on a local TASK, suggested events throughout the Midwest, organized an exhibition about TASK which traveled to two other university galleries, and worked with Herring on this book. It also includes numerous letters and comments from TASK organizers and participants, a list of specific tasks proposed by participants at the Hirshhorn, and many, many photographs documenting the events.

Herring and the various TASK organizers are straightforward about sharing the problems as well as the successes, aspects of the events that fell short of their hoped-for results as well as the un-imagined benefits. Herring’s event recipe includes notes for planning an event, a sample list of materials to have on hand for different size groups, and a sample waiver for photo/video release. He’s giving away the idea and the structure. He’d like to be notified about the events, but acknowledges that many have been organized without his knowledge in a variety of situations including a corporate retreat, a breast cancer survivors’ group, and a class of English-for-beginners in Rome. Herring’s final comment is that TASK is a creative outlet, but it is also a direct (and self-directing) point of access to contemporary art. That’s certainly something the world could use more of.

Oliver Herring, TASK (University Galleries, Illinois State University, Normal: 2011) ISBN 978-0-945558-34-7

Brian O’Doherty, Studio and Cube

This small volume, a sequel to O’Doherty’s earlier writing, Inside the White Cube; The ideology of the gallery space (1986, published in 1976 as a series of articles in Artforum) is the text of a lecture delivered in 2006 at Columbia University. Inside the White Cube opened its readers eyes to the implications of the environment in which contemporary art had come to be exhibited. It changed the thinking of the art world, and indeed, its vocabulary; the white cube is now regularly used as shorthand for museum and gallery interiors.

Inside the White Cube was the first systematic analysis of the function of the highly-conventionalized spaces developed for the display of contemporary art. O’Doherty suggested that their rhetoric of neutrality intentionally isolates the art within from all the messy contingencies of outside life: current social, political, economic and moral issues. Not only had such spaces come to define whatever they contained as art, but they had become the art itself. This was written after Marcel Broodthaers had been creating museum fictions for a number of years, and around the time that Hans Haacke had begun to investigate the relationship between art and its patrons; but it was before any of the literature of critical museum studies and long before the term institutional critique was applied to the work of a group of artists.

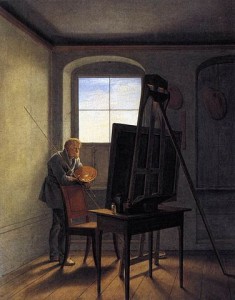

The artist’s studio has become the subject of enough exhibitions and books during the past few years that one might call it a fashionable subject. Why, I don’t know. Studio and Cube is unlikely to have the significance for the study of artists’ studios that O’Doherty’s earlier essay had on the understanding of the ideology of the display of art – but that is not really fair, since the subject of Studio and Cube is actually the transformation of the status of the artwork itself. O’Doherty has two overriding points: 1) The displacement of attention in late modernism from the artwork to the artist,… applies also to … the studio and 2) that there is a connection between the self-referential creative process and the autonomous artwork in the gallery. Thus, we have returned to the white cube.

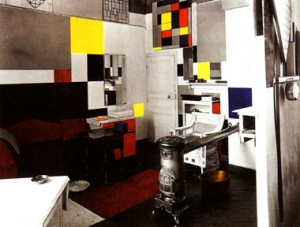

The book, in the manner of good lectures on art, is filled with anecdotes about artists (Berenson visiting Matisse’s studio, Stuart Davis’ dislike of the countryside, Mondrian dancing) as well forty-three interesting illustrations — either of artist’s studios or representations thereof, even if they are mostly the usual suspects. But I have a real quarrel with O’Doherty’s discussion of Mondrian and his studios, which along with Brancusi’s he credits with having a major influence on the white cube. He illustrates Mondrian’s Paris studio and the first of the New York studios in black and white, the second New York studio in color; and it is the color image on which he focuses. It shows an area where the artist had pasted small pieces of colored paper to the walls as a means of trying out compositions for Victory Boogie Woogie, his final painting, which is shown on the easel (above); the rest of the wall is white, and O’Doherty claims that Mondrian thereby excluded everything other than the painting from the studio. He ignores the fact that in the image of the Paris studio, Mondrian had enlarged his rectilinear compositions to cover the walls themselves.

One can interpret Mondrian’s extending his paintings onto the studio walls as a continuation of the Arts and Crafts movement’s melding of art, craft and decoration into a gesamtkunstwerk, ignoring their respective hierarchies; or see it as prefiguring installation art. In either case, the work is anything but isolated. And it was surely Mondrian’s Paris studio that was behind Clement Greenberg’s unexpected comment (presumably about life after the revolution), in a review in The Nation, Reconsidering Mondrian’s Theories, that With Marx, he anticipated the disappearance of works of art — pictures, sculptures– when the material décor of life and life had become beautiful.

Brian O’Doherty, Studio and Cube; On the relationship between where art is made and where art is displayed (A Buell Center/FORuM Project, New York: 2007) ISBN 1-883584-44-2