“Am I being too boring? I can tell you stories of all my boyfriends to spice things up.” No spice was needed for the 20 people gathered at Taller Puertorriqueño on Aug. 4 to hear artist Kukuli Velarde.

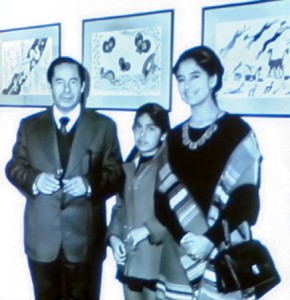

Nestled in the bookstore between rows of books, Velarde, a resident of Philadelphia since 1997 and a Leeway Foundation grantee, Pew Fellow (2003) and USA Knight Fellow (2009), spent two hours guiding the audience through her Peruvian heritage and life stories, the room often laughing from the artist’s wit and sighing in her creative profoundness. Her opening slideshow of common Peruvian images was mixed with black and white photographs of her childhood. The artist danced in place as Peruvian music guided the sequence. From the beginning, it was clear that knowing where Velarde came from was integral to understanding her art.

A child artist, Velarde held her first exhibition at age 10. Feeling the weight of responsibility and expectation, she gave up painting by age 23 and moved first to Mexico, then New York. Velarde discovered ceramics saying, “I felt something that I had never felt in my life working with clay.” Diving into the medium, she explored themes of gender, identity, and her Peruvian heritage.

She became interested in the effects of colonization on Latin America’s indigenous in 1992 during the 500-year celebration of Columbus’ first voyage. “It pissed me off,” she said. She channeled the anger into a series: We, the Colonized Ones.

“I didn’t know I was creating a series,” she said, “I was just upset and I had the need to say something about it.” She began carrying her ceramic indigenous babies in the subway to engage with fellow commuters. When an installation piece of the babies hanging along a Columbus Day parade route was censored, her protests with collaborator Ana Ferrer earned recognition for freedom of expression.

“They say I have a very tough personality,” Velarde said. “I have a lot of opinions.” More than anything: she has a lot of ideas. As the artist presented a chronology of her works: La Santa Chingada and Super Buro, 1992; Pure Love at the Lima Biennial, 1999; and Filosofía de Retrete, 2003, the unending ability for her to create was obvious. Inspiration comes from everywhere, from machismo encounters to Mexican soap operas. “Life feeds your work,” she explained.

Her 1997-2005 series Isichapuitu epitomized this philosophy. Flipping through a Mexican archeology book, her eyes settled on a Pre-Columbian ceramic figure. She liked it so much she said, “I wanted to believe I had created it. I even thought it looked like me.” The results were 74 ceramic figures, each with the same base, but individualized to represent a different thought. Titles include: “Thirst,” “Como Perro en Carratera (Like a Dog in the Highway),” and “Sometimes I am Kind of Flaky.” The works combine wit and passion, causing the viewer to chuckle and then analyze what made them do so, internalizing the emotion each piece exudes.

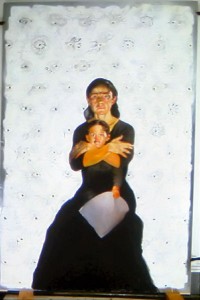

Central to Velarde’s talk was her father, inspiring her in overt and subtle ways. He would ask, “Porque no pintas?” (Why no paintings?) He would draw out the “a” for emphasis. “My father believed I was the best painter in the world, he really did,” Velarde explained. She began painting again in 2004, the year her father’s heart began to fail. One of her most spectacular works is a black marker mural shown at the Barry Friedman gallery in 2010. “My father would say, ‘My hand has memory,’ and I think it is true.” For the piece, Velarde let her hand go, conjuring images from her childhood as she drew around a video projection of an interview with her father. After the exhibition, the mural was whitewashed, releasing it back to memory.

Her recent three series — Plunder Me Baby, The Cadaver Series, and Patrimonio — draw inspiration from Pre-Columbian stirrup spout vessels, colonial portraiture, and Catholic iconography. She keeps with the central motif of using her face on the figures, the artist defiantly subverting stereotyped slurs. When asked why she always uses her portrait, she said, “To talk about something very personal, I have to use me.”

At the end of the talk, the audience discussed Latin American art today. Her advice to young artists: “Always do whatever you want. In art, you should have that complete freedom.” Velarde excels in translating her cultural heritage into a contemporary dialogue, taking images of Peru and childhood and letting them retell their story.

Everyone left Taller Puertorriqueño dancing.

–Rachel Heidenry is a writer living in Philadelphia. She specializes in public art with previous work focused on Salvadoran mural painting.