The title of the current exhibit at Margaret Thatcher Projects, Cut, Drawn, Painted: Works on Paper, expresses the gallery’s primary focus: Process Art. I interviewed five of the ten artists from the show, and the late Agnes Martin kept recurring in conversation. Martin–paragon of the artist’s work ethic, aspirant of unobtainable perfection, peer of the driven artist who finds joy in doing–remains vital for many contemporary process artists. (All of her quotes in this review are from Writings, Cantz, 2005.)

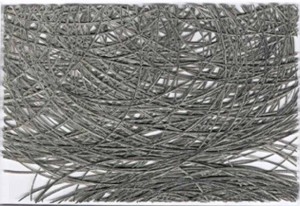

I think of lying face down in grass when I look at Adam Fowler’s framed, shallow, cut and layered drawings. The wealth of details draws me in close; eye, mind and cheek share textured memories of a flattened, cool lawn. Gesture is Adam’s chief subject matter, the path of his consciousness and the most obvious connection to Martin. His lines gather energy as they bunch and overlap, while Martin’s loosely ruled marks divide and multiply into orderly rectangles, making a scaffold for rest and emptiness. If Agnes Martin had relaxed her line, Adam Fowler would be the result.

After making many billowy, curving drawings with a composition in mind, Fowler cuts the negative space away from each line, creating skeletal remainders like dried leaves with only the veins remaining. He stacks and intermingles the pieces. Work is piled upon work, and distinguishing the layers is a job for the keen-sighted. I recall Martin’s description of work as “part of the process of life in which we cannot perceive the beginning or end of our function.”

As I look, I’m overwhelmed sorting lines and calculating effort, and, for relief, I switch back to experiencing the work as a whole. Mysteriously, Fowler’s work becomes a metaphor of complex nature. Fowler’s grass-like lines point me toward constructing a tidy, romantic, intellectual version of life and nature. He harnesses confusion: getting lost in lines is a prerequisite of making sense of his work.

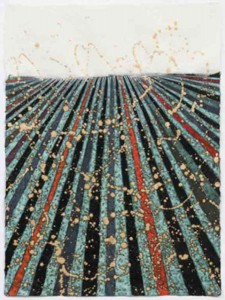

Where Fowler uses line as subject, Barbara Takenaga employs line as limit, inventing heady, cosmic patterns that emanate from a horizontal. Agnes Martin said, “When I draw horizontals, you see this big plane and you have certain feelings like you’re expanding over the plane.” Martin was content drawing a single horizon line, but Takenaga uses it as a source or font of imagination.

New works by Takenaga involve the artist dripping paint on paper and meticulously painting stripes around the splotches, freezing chance in the process. Chance reengages her with surface and gives her a toehold for pushing back against this fertile horizon.

Concerned with the awareness of nature as well as the tangible end result, Tad Mike works outdoors, painting calligraphic lines and organic patterns on paper, using thistles or rocks dipped in walnut ink as his paintbrushes. Tad sits alone, receptive to beauty, uniting the look and feel of nature in deliberate, sensitive marks and designs, continually braiding receptiveness together with material skills.

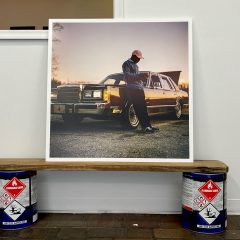

Stylistically apart from the group and hailing from the opposite shore of Process Art where sculptors Lynda Benglis, Richard Serra, and Robert Morris experimented with action-art and things got messy, Rainer Gross experiments with paint. He doesn’t limit himself to line and doesn’t seem concerned with purity; in fact, he uses commercial logos in “contact painting” (his term) that involves pressing together two wet paintings and then prying them apart.

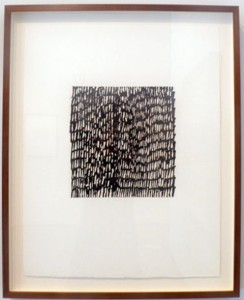

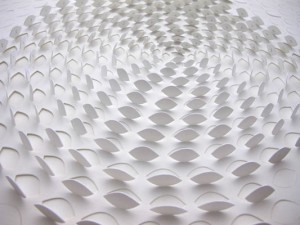

Leaving painting materials behind and keeping the surface, Jaq Belcher considers paper a pure field of energy. She finds ways to work that reveal and enhance rather than interrupt its energy. She draws and cuts a pattern into the sheet, counts and numbers the cuts, raises the pieces–making the work three-dimensional–and seals the work in a frame. For Martin, perfection cannot be represented, but Belcher flies awfully close to the hot sun of purity: it’s her motivation, meditation, and result.

Broadening the definiton of Process Art to include “allowing” as an action, Gross, and to a degree Takenaga and Mike invite chance into their works. Fowler and Belcher, the two paper cutters, eschew chance in favor of a more standardized and repetitive approach that is its own kind of Zen. Displaying contrast more than cohesion, the show jells around a shared motivation to discover new extremes within the work ethic.

Cut, Drawn and Painted is up until August 10 at Margaret Thatcher Projects in New York. The show also features Frank Badur, Libby Black, Howardena Pindell, Winston Roeth, and Nan Swid.

–Elizabeth Johnson writes from Easton, PA. She currently has a solo show of her plein air paintings at Schmidtberger Fine Art www.sfagallery.com in Frenchtown, NJ.