“The most important thing art can do is create a conversation between people in a room.” Martha Rosler’s quote would appear to be an inspiration for artist Ashley Hunt and his talk at Temple Contemporary on September 10. The gallery was packed with professors, students, and art enthusiasts ready to engage in the discussion.

“Questions of Art, Participation, and Social Engagement” was a conversation between Ashley Hunt, Philip Glahn, Associate Professor of Critical Studies and Aesthetics at Tyler and the audience. Glahn posed questions and led the discussion. The evening was planned as a discussion in four parts, but with an hour and a half allotted and questions from students, only two topics were covered.

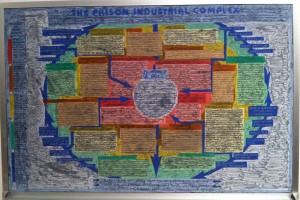

Hunt’s work directly merges art and activism. Many of his projects focus on prisoner rights and mass-incarceration, utilizing photography, word, video, and mapping. As he explained, “Art and activism are not lined up next to each other, rather they have emerged out of each other. I find them to be the same thing.” Placed into a fabricated category of “socially engaged art” or “social practice art,” Ashley questions the paradox of these labels. “All art is social,” he said.

Focusing on the landscapes prisons are situated in, Hunt’s recent series of photographs makes visible their perceived invisibility. The photographs picture depopulated terrain, lights shining powerfully in the distance. Each is captioned with the number of prisoners, yearly budget, and location. The series brings up questions of land usage, the presentation of punishment, and public safety, connecting society’s imagination of prisons with their physical reality. Hunt explained, “Art can draw connections between what is erased and concealed.” Indeed, the series excels in connecting a tangible issue with abstract questions of subsequent meaning.

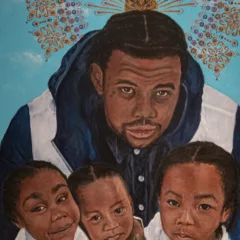

Weaving conversation into his pieces, Hunt is skilled at democratizing the expert, allowing ex-prisoners, grassroots activists, scholars, artists, and volunteer museum docents to both interpret and share in his work through various means like interviewing people in the documentary Corrections; inviting community members into the creation process in Communograph; and placing pastels and chalk in gallery assistants’ hands in A World Map: in Which We See…

Hunt is all about facilitating and then getting out of the way. “The art world doesn’t know how to let communities be the intellectuals. This is why they label and add hyphens: ‘political-art,’ ‘social-art,’ ‘activist-art.’

Meanwhile, the audience’s questions — the majority posed by university students — centered on the role of the artist. Was the social practice artist a mere distributor or still producing knowledge? How do we get people to slow down for these types of works in such a fast-paced world? Would the work be more successful if it were directly presented to power authorities rather than to the general population and art world?

Hunt’s response highlighted the difference in political art and social practice art. “Traditional political art confronts the state or the power authority. A lot of people do it and it is important. For me, I think it is not just the critique that is needed, but also the constituency to support. My interest is working in the context of movement-building.”

To the question of whether he had to learn something else after he graduated art school, Hunt replied, “I think there is something about art education that is really radical. Art education says don’t paint like this because that is how you paint, but because it is the way you need to paint.” He went on to explain the benefits of an artistic mindset for the activist field: artists take time to slow down, are less urgent, and are used to processing.

One audience member cut straight to the core of the topic, asking Hunt, “Why call your work art in the first place?”

Hunt smiled, responding: “I’m an artist and that is what I have pursued in my life. I came to this through the discourse of art. I think prisons are just as important as talking about cubes or grids.”

Throughout the evening, Hunt and Glahn brought up several themes: what an artwork does vs. what an artwork is; how a work’s performativity reflects its identity and meaning; what the roles of artist, work, and audience are within social practice art; and who is teaching whom.

None of the big questions were answered. Rather, they were illustrated and discussed and left open for continued dialog. In fact, the conversation would have been better suited for a weeklong forum or semester symposium. An hour and a half time restraint could barely start the conversation.

Tyler School of Art, Live Arts, and the City of Philadelphia Mural Arts Program and muraLAB sponsored the event.