Are You Working Too Much? Post-Fordism, Precarity, and the Labor of Art (Sternberg Press, Berlin: 2011) ISBN 978-1-934105-31-3

The eleven articles in this collection were previously published by the on-line e-flux journal; they have been assembled with a brief introduction by Julieta Aranda, Brian Kuan Wood and Anton Vidokle, who raise the question why should so many talented and hyper-qualified artists submit themselves willingly to a field of work (that is, in art) that offers so little in return for such a large amount of unremunerated labor? Readers looking for a straightforward answer to the question or even a discussion of specific examples will be disappointed, for these articles address the question at the meta level. They discuss neither the actual labor of art-making nor the specific economics of supporting an art practice.

The book is a collection primarily of neo-Marxist approaches to the position of artists, academics and other, largely free-lance, cultural workers within the current, globalized economy. The essays contain a lot of jargon drawn from economics, political science, psychoanalysis and cultural studies, and may be useful to readers who want to see how terms such as post-operaist, intent worker, semiocapitalism, cognitive capitalism, subjectivities, and cognitartan are used in context. It may also be a useful introduction, albeit at second hand, to the ideas of Maurizio Lazzeratto, Slavoj Zizek, Paolo Virno, J.K. Gibson-Graham, and Giorgio Agamben, among others.

The articles are by Hito Steyerl, Liam Gillick, Tom Holert, Irit Rogoff, Marion von Osten, Diedrich Diederichsen, Lars Bang Larsen, Keti Chukhrov, Franco Berardi Bifo, Antke Engel and Precarious Workers Brigade.

Commerce by Artists Louis Jacob, ed. (Art Metropole, Toronto: 2011) ISBN 978-0-9809184-4-1

In selecting work by more than fifty artists and collectives for this thematic volume, Louis Jacob looked for projects done since the 1950s that actually engage in commerce, rather than represent it. Jacob defines commerce as an act of exchange, so that money is only one among many valuables which might be part of the transaction. He does not bother with the straightforward sale of an art object in exchange for cash, although with many examples the artist received cash, but for something other than art.

Examples of exchanges involved labor (in 1973-74, Mierle Laderman Ukeles offered to clean a museum’s floor and front steps as her artwork; the museum in turn offered an exhibition of her performance of Maintenance Art); space and visibility (Maurizio Cattelan sold the billboard that he was alloted at the 1993 Venice Biennale to an advertising agency); sex (Andrea Fraser offered s sexual encounter and videotape of the activity in 2003; the collector exchanged cash); used household goods (Martha Rosler held a garage sale in an art space in 1977; she will hold another sale at MoMA this autumn); the shirt off one’s back (during one day in 1995, Ben Kinmont offered anyone entering agnes b (NYC) to exchange the shirt he was wearing for any shirt available at the store); identity (Keith Obadike offered his blackness for auction on Ebay in 2001; Ebay shut down the sale after four days); and a name (Theodore Fu Wan filed a legal petition to change his name to Theodore Saskatchewan Wan, after the town Theodore, Saskatchewan).

Jacob’s writing is confined to an introduction which discusses his interest in the subject and includes several examples not in the collection itself. Each art project is illustrated and commentary is primarily in the form of artists’ statements or interviews with the artists. One particularly interesting text is by a member of the collective, Toxic Titties, two of whose members took jobs in 2001 as models for one of Vanessa Beecroft’s performances. They needed the money Beecroft paid them, but the power relations of the work and their discomfort (which as artists whose collective is focused on creating performative events that undermine familiar notions of gender, sexuality and class within pop culture, feminism, and art commerce, was considerably stronger than the other, mostly professional, models) provides important criticism of Beecroft’s performances from their previously (and intentionally) anonymous participants. The book follows a series of resource volumes that Art Metropole has published, recording artists working in specific media, or around single themes: video (1976 and again in 1986), performance (1979), books (1981) museums (1983) and sound (1990). Jacob’s selection, with examples by both well and little-known artists, is a welcome addition to its valuable predecessors.

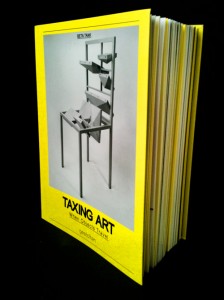

Beta Tank Taxing Art; When Objects Travel (Gestalten, Berlin: 2011) ISBN 978-3-89955-346-8

Beta Tank describes itself as a conceptual design practice, meaning it produces objects that are more important for the ideas they raise than for their solutions to given problems; their intent is to shake up conventional thinking about design. Eval Burstein, Beta Tank’s principal, found that on moving from London to Berlin he encountered a business climate significantly influenced by an elaborate system of tax laws. None of these was as baffling as the broadly internationally-accepted Harmonized Commodity Description and Coding System, which is used by customs officials to classify imports and exports for purposes of determining the tax rates; rates are always lower for art than for other commodities. He has written a thoughtful and humorous account of a project he embarked upon for an installation he called Taxing Art, which included a steel table whose top is formed by wooden blocks that can be manipulated so that it is rendered functionally useless; at that point it can only be considered a work of art. Beta Tank designed the installation to test the actual application of the coding at various, international customs departments. His efforts demonstrate that, whatever the intent of the coding, its implementation – and, hence, the legal definition of art for tax purposes – is conducted by a series of shipping agents, customs agents and customs officials whose knowledge of contemporary art and design, or the questions they raise, is marginal at best.

Anyone who has been involved with packing and shipping artworks will appreciate much of the story, which documents the installation’s mishaps due to the crate’s design and its mishandling. But its customs exploits might have been written by Kafka. In Barcelona the work was classified as a table, in Istanbul as parts of a wooden (sic) table; in Doha it was classified as personal effects and in Berlin it finally ascended to the category of art. Lest these seem like marginal issues, a case that received surprisingly-limited international attention was settled by by the European Court of Justice in 2010: the British gallery, Haunch of Venison, imported works by Dan Flavin and Bill Viola to the U.K.; the decision, which the court upheld, was that they were electrical goods and audio equipment for purposes of import taxes.