For audiences raised on computer animation and movies, going to the theater is a refreshingly real dramatic experience. After all, audiences pack Shakespeare in the Park performances so that they can see living actors perform. Unadorned theater is part of our cultural life.

Maybe that’s why the use of an animated, twisting version of Van Gogh’s “Starry Night,” digitally projected over nine screens, fell so flat for me as part of the set design for the Opera Company of Philadelphia’s production of La Bohème, which closed Sunday after five performances.

This production of Giacomo Puccini’s classic opera was widely touted as being “inspired by masterpieces at The Barnes Foundation & The Philadelphia Museum of Art.” But inspired does not seem quite the right word, as rather than drawing on the French Impressionist works from those collections for set design ideas, the several Impressionist masterpieces included in the show were simply projected on the walls of the theater as the set.

Perhaps the creative team behind this production doesn’t believe anyone has a long enough attention span to sit through an opera with a static set anymore. But actually, the moving set made the viewing experience almost unbearable.

It is certainly appreciated when cultural institutions work together to experiment with the presentation of art, but this collaboration just feels like a cheap gimmick to lure in tourists. Some of the paintings are even inserted as if they have been painted by Marcello, the opera’s painter protagonist — Van Gogh’s “Sunflowers” was digitally edited to include the signature “Marcello” – which jars the viewers out of their suspension of disbelief.

The first act has a slideshow of projected Impressionist masterpieces as its background, which slowly pans from side to side or zooms in. At first, it seems like Marcello is painting Renoir’s “La Prairie” and “Woman with Fan” from the Barnes Foundation collection, since the pieces are projected onto a canvas prop as well as the wall behind him. But the unbearable slideshow continues as Marcello moves away from his canvas, severing any logical connection between the opera and the set projections. Furthermore, brightly colored depictions of spring seemed out of place when the characters were singing about freezing to death in the Parisian winter.

When the seamstress heroine Mimi takes the stage, the slideshow turned to several of Renoir’s portraits of brunette women, whose looks inspired Mimi’s character design. But regardless of this character-to-painting connection, the giant projections of painted faces are just distracting, especially when there are the actual living faces of singers on-stage. And after 20 minutes of constantly shifting projections of art, sea sickness sets in. If you weren’t nauseated by the motion of the pictures, the laughable animation of Starry Night which appears at one point will do the trick.

A similarly lamentable creative adaptation was made in New York a few years ago when William Kentridge served as artistic director of Dmitri Shostakovich’s The Nose, based on the classic Gogol story. The majority of the set was an animated digital projection, leaving the “real” elements, sets and singers, completely minimalized. It felt like the original 1930 St. Petersburg production of “Nose” that was panned by critics, not the exuberant, colorful Valery Gergiev-led production which revived interest in this lost classic, and which by the way was full of extravagant, tactile sets. I fear the Philadelphia production of La Bohème, like Kentridge’s The Nose, suffers from too much reliance on digital projection technology.

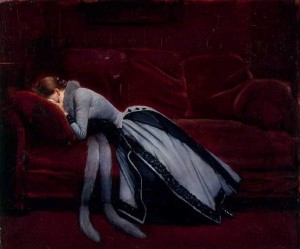

There are a few moments where the projection idea works. Act three opens outside a tavern, where Marcello mimes painting a landscape that gradually appears on his canvas. Then it fades in as the background of the scene, like the real-life vision which Marcello took as his subject. For once, the device is integrated naturally and logically. But then in act four, Mimi is wearing the same outfit as the female subject of “After the Misdeed” by Jean Béraud, which is projected for longer than usual, and she lies in the same shape as the woman in the painting. The doubling of the image in the staging and the set has no reasonable dramatic purpose and brings us back to pointless projections of essentially unrelated artworks.

Overall, the projected paintings were almost entirely awkward and clunky interruptions from the beautiful music of Puccini and the vocal talents of the cast. Bryan Hymel, the tenor who ably played the role of Rodolfo, said in publicity materials that he thought of the projected artworks as images from his character’s internal world. But to a viewer, the paintings were too realistic and recognizable as famous works to be open for interpretation as a mental space.

Perhaps declining public interest in opera has made digital projection necessary as a cost-cutting measure. It’s nothing less than tragic that the Opera Company of Philadelphia can only do 15 performances per year and has to charge exorbitant rates for tickets. But uninspired digital projections like the ones incorporated in La Bohème is not the answer, and will only scare away viewers.

It was only for part of act two that the projections of art disappeared and the stage filled with performers, playing Parisians outside and inside Momus, the café where the Bohemians dine. However, the large group of extremely talented performers that appeared in that scene – including a fire-breather, acrobats, dancing waiters, and an insanely personable lead child performer – seemed like they had received less attention from the producers than the lifeless digital projections, and that is a sad state of affairs for any theater performance.