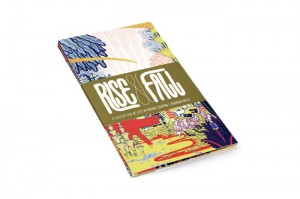

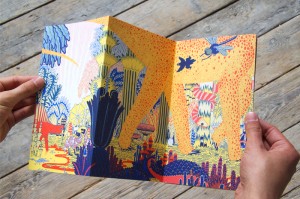

This surprising and seductive publication tells the story of the prehistory of the natural world, from the rise and fall of the dinosaurs and a meteor falling into the ocean, to the development of mammals, and ultimately, primates. The narrative unfolds entirely visually, with no text at all, across both sides of a concertina fold. Lidberg’s style betrays his knowledge of Japanese print-making but is hardly derivative, and he has great sophistication about how the illustration will look in printed form. It is characterized as a book because of its publisher, and it has an ISBN, but as far as I’m concerned it is a very large edition print which has been exquisitely produced. It is good enough to frame, except that to do so would eliminate the sense of the story evolving over periods marked by the folds. I enjoy seeing it on a shelf in my study, as will anyone, of any age, who appreciates good illustration.

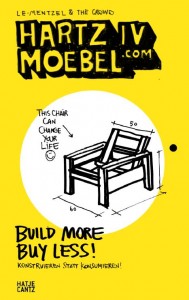

Van Bo Le-Mentzel et al, Hartz IV Moebel.com; Build more, buy Less (Hatje Cantz, Ostfildern: 2012)

The title of this handbook derives from the name of the controversial German welfare system (Hartz IV), hence, Welfare Furniture. Its modest author, in the personal tone he adopts throughout, suggests it is intended for four groups: 1) DIY fans, 2) interior design fans, 3) start-ups and marketing managers, and 4) Communists and other crazy people. He says he isn’t used to running a furniture company, but is clearly pleased that he has put thousands of people to work without any overproduction….Although no one is paid, everyone is motivated. He was able to complete the book in a month with lots of help from his friends – all of whom are credited.

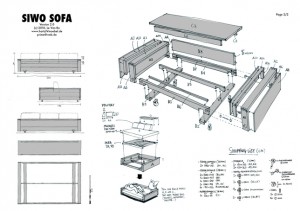

Le-Mentzel acknowledges that he began with no skills at all and learned his meager carpentry at adult ed classes. His furniture’s economy of means is a result of the desire that it cost as little as possible, use the least amount of wood (since he doesn’t have a car in which to haul it) and take as little time as possible. The designs are loosely based on Modernist classics (some of which are illustrated), but they evolved through feedback from users, who can obtain free plans on the web. One design is up to version 3.0. The book has a stitched binding that should hold up to handling throughout the building projects.

The author occasionally puts out calls for help with Guerilla Lounging, his name for unauthorized improvements in public places such as airports, train platforms, and elevators, to make them more people-friendly. Le-Mentzel clearly enjoys the community he meets by offering free designs and calling for help with unofficial beautification projects. The book is filled with photographs of a number of the widespread group, with the furniture they built and short stories about their lives: the engineer in Hannover who left the rat race to build sound speakers, the design professor and students who built furniture for a bakery café in Stuttgart, staff at the Goethe Institute in Montreal, and the 77-year old Dutchman with Parkinsons. Le-Mentzel actually requires would-be users of his furniture designs to fill out a form about how they heard of him, what motivated them, and promise to send a photograph of the resulting furniture.

And the furniture? It includes everything necessary for a small apartment: a table and side chairs, desk, lounge chair, adaptable stool/table/shelving unit, two lamps, a wardrobe and a clever couch that converts into a bed that is actually comfortable for sleeping. All have simple and tasteful designs. I can’t say I’ve tried to make any of them – I have yet to take that adult ed class. I plan to pass the review copy on to the Anarchist group around the corner. The book should make a good gift for friends whose ideals are larger than their bank accounts, and those who take pleasure in doing things themselves.

Bernini; Sculpting in Clay, (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York and Yale University Press, New Haven: 2012) ISBN978-0-300-18500-3

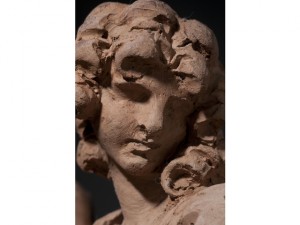

This splendid catalog is the perfect gift for anyone who loves sculpture and will be of particular interest to sculptors who model. After all, it includes the majority of the extant models by one of the great sculptors of all time. Bernini’s work in clay served several purposes, as did drawings (which exist for most of the projects for which clay models survive). Some were initial, rough sketches of the idea (bozzetti), others were more finished (modelli, or modelli piccoli), possibly intended to show the patron, or to guide the workshop assistant who would actually do the carving. Then there were life-size models (modelli grandi), made either to be placed in situ, as a way of judging how the work would look, or to be used in the casting process.

Anthony Sigel’s Visual Glossary is a Rossetta Stone to the ceramics. With illustrated details he shows the clues to every stage in making the models, including their assembly, bases, and buttressing, measuring points and layout marks, surface decoration, and Bernini’s signature modeling techniques. He also discusses the clay, tools and tool marks, evidence of damage and restoration, and the various technical methods used to examine them, with particular attention given to fingerprint analysis and radiography. The photographs are marked to indicate points such as the direction in which Bernini pushed the clay, and the text is as clear and direct as the subject warrants. I have never seen the study of sculpture explicated as finely as this. It is a model demonstration of the amount of information that can be obtained by careful, visual examination, and indicates that connoisseurship yields considerably more information than quality and attribution.

Each work in the exhibition (and a few not available for loan) has a long entry which includes condition notes and is illustrated with numerous details and comparative material. The catalog includes essays by two curators and three academic art historians, covering everything from Bernini’s training and early work, the relationship of the models and drawings, and the reception and public function of the models, to the historiography of their study in the Twentieth Century. But the article that is likely to be of most interest to a general audience and particularly to artists is Andrea Bacchi’s on how the terra cotta models were used in Bernini’s workshop. It gives an extraordinarily clear idea of the administrative demands of a successful artist in the Seventeenth Century, as well as how broadly accepted workshop assistance was. The closest contemporary model is the large architectural practice, where no successful architect works out details, such as interior finishes, or the plans for the rest rooms.

Bernini was engaged with huge projects, such as his numerous commissions over half a century at St. Peters. He and assistants spent ten years on the Baldacchino alone, and for the decoration of the pilasters lining the nave, he employed about forty sculptors (anyone who could hold a chisel according to Jennifer Montagu). While the master himself always created the bozzetti, everything else, from the modelli to the actual carving might be done by assistants of varying experience and ability. His most competent assistant might only be given a drawing from which to develop the modello. Both patrons and the public understood the multiple hands involved. Filippo Titi’s 1663 guidebook to Rome names the four assistants who each produced a large figure for Bernini’s Four Rivers Fountain.

This catalog will have a long life beyond the exhibition it accompanies, and is likely to be treasured by artists, art historians and the serious public.