The essay accompanying Dematerialization, up now at Pterodactyl Gallery in Kensington, includes the observation that “many contemporary artists and art productions have aligned with minimalist Donald Judd’s 1965 declaration of ‘disinterest in doing [painting and sculpture] again.’” In the work on display in Dematerialization, curated by Jamie Png, this “disinterest” has extended to a negation of artistic intent, narrative, and in some cases even aesthetic appeal. Many pieces conceptually show art as providing an open-ended experience, rather than an intentional creation, while others question the essential presuppositions of the art world. This type of experimentation is a delicate tight-rope for artists to walk, for while most pieces here are fresh and enjoyable, some veer too far off into the insubstantial.

Brooke Sturtevant-Sealover’s work greets visitors to the gallery like a Zen bell introducing the show’s theme of meaning in meaninglessness. Her colored pencil-and-vellum images resemble pseudo-scientific electrocardiograms, drawn from a plant. Human logic or narrative is right away sidelined by the slow, inevitable growth of the eternally vital natural world, which Sturtevant-Sealover has translated into visual language as a stream of colors.

K. Malcolm Richards’s satirical “Proposal” best captures the show’s puzzling contradictions. Richards outlines an art project wherein he would take over a building’s climate control system and spend a day playing with heat and cold, mimicking the temperatures in various cities. “In seeking employment for the day, I am providing a service, an aesthetic experience, and a potential interdisciplinary dialogue,” Richards writes, ticking off the purposes of artistic work that this piece, in its nature as a parody, seems to negate. It may be a sign of the times that the definition of “artist” can theoretically be extended to include climate control technician; but the joke is a bitter one in that Richards’ asking price for eight hours’ work is $74.

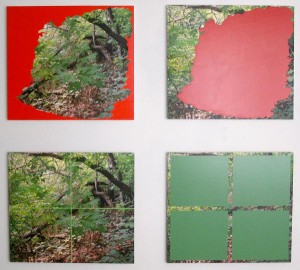

The puzzles continue in “Forest Walk” by Todd Keyser, where the artistic activity is in the obstruction of an image.

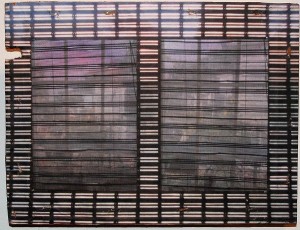

Similarly, Ted Carey’s “Double Backdoor Chipped” replicates the sense of looking out a screen door at your backyard, all but entirely obstructed by dense black lines. In this and Keyser’s work, the artist’s labor has become the obstruction of images, which speaks to the cluttered mindset of a contemporary artist’s worldview.

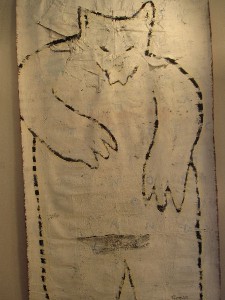

Carey’s monster “Carl” appears in this show like the ghoulish specter of representational art. With pants for a face, and random cipher-like letters scrawled in his body, Carl is the yeti (or abominable snowman), appearing barely outlined in an arctic snowstorm to terrorize the happily dematerialized viewer.

“War Song of My Ancestors” by Tobin Rothlein consists of twelve iPod shuffles strung up in the ceiling with headphones dangling down, each playing one looping hour of Rothlein’s 12-hour marathon singing of the U.S. national anthem in a marketplace in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. The artist is invisible, his task obscure, and the “work” a 12-hour experience on the other side of the world. The singing voice is a unique representation of American cultural presence around the world, as a nagging presence that is ignored like any other background noise.

Kristin Grey Apple’s videos are like fuzzy, out of focus memories. The concept of dematerialized meaning or intent is useful here, and appealing as a force that can imbue meaning into even the smallest of elements in the three videos by Apple on display: “Recognitions,” “Arrowhead,” and “At times, however, I will simply attempt to respectfully encounter whatever is there in front of me. This reminds me of laying in the crib earlier in life.” The short films feature non-linear imagery of the sky and nature inter-cut with brief glimpses of human faces, or in the case of “Recognitions,” a long, painfully close look at the facial expressions and bearing of a stranger Apple filmed in a cafe. Each of the films can be taken at face value or as open-ended stories told in a stream-of-consciousness, narrative style.

On the opposite end of the gallery, Colleen Rudolf took robotic holiday lamps of Santa and Mrs. Claus and stripped them of their identifying outfits, then left them uselessly crawling on the ground. The original intent of the object is gone, and any original intention has been subverted into a show of useless futility. The fact that the robots are originally Santa Claus and his wife introduces a sort of cynical humor into the play of elements in this piece.

Other open-ended, experiential works in the show use the space of the gallery to interrogate the meaning of an artist’s work. Marie Manski created a small, confined Japanese-style room, like an invitation to profound meditation. Isn’t that what people do at art galleries? Leah Cooper’s “Notated” is slanted contour lines along a corner of the gallery, skewing the viewer’s sense of perspective, likewise mimicking an intentional aesthetic disorientation that people seek in art.

Also in this diverse show are Bart O’Reilly, Elizabeth Hamilton, Ben Will, Rodney Thoms and Jassie Rios. All the pieces in Dematerialization attempt to provoke a dialogue with the viewer. The Philadelphia artists assembled for this show represent a cross-section of struggles with meaning and the definition of artistic labor, best shown in the works of Keyser, Sturtevant-Sealover and Apple. But some of the pieces, like Rudolf’s Mr. and Mrs. Claus, feel more like a cynical joke than a sincere engagement with the ideas of Dematerialization. Despite being conceptually stimulating, the final impression of Dematerialization is that of a somewhat mixed bag.

Dematerialization will be up at Pterodactyl through Nov. 30.