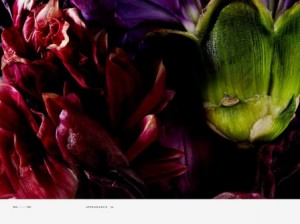

Makoto Azuma and Shunsuke Shiinoki Encyclopedia of Flowers (Lars Muller Publishers, Zurich: 2012) ISBN 978-3-03778=313-9

This extraordinary volume will certainly appeal to connoisseurs of flowers, but should be of equal interest to anyone susceptible to the seductions of color and form. Azuma is considered an haute-couture florist (whatever that may be), but the wonderous photographs, by Shiinoki, show no actual arrangements as they might exist in life. All are details in which groupings of flowers are freed from gravity and the need to be grounded in a vase or on a kenzan (flower frog). Some photographs are taken from surprising angles, and all of them focus on juxtapositions of color, texture and forms, and sometimes unlikely botanical groupings, and all become visual poetry.

In his short introduction (the book is almost entirely illustrations) Azuma refers to the almost universal use of flowers as offerings and the petrified evidence of cut floral offerings to the dead from the Jomon period (10,000-200 B.C.). His own approach to flowers is reverential, and he is acutely aware of the violence done to living things that precedes his creations. The botanically-inclined will appreciate the proper, binomial identification of the more than 2,000 flowers pictured. The sensitive and restrained design and exquisite printing, both Japanese, are a fitting tribute to the subject. This book is a very beautiful object.

Susan Mullin Vogel El Anatsui; Art and Life (Prestel, Munich: 2012) ISBN 978-3-7913-4650-2

El Anatsui is the only artist within the globalizing contemporary art scene to reach the highest level of acclaim while living not only outside a major art center, but also on a continent largely ignored by the contemporary art world. He has created a technique and form that is entirely his own, to produce work that speaks to international audiences on multiple levels. This exemplary monograph is what all artists would hope for, with biographical information, close attention to individual artworks, serious critical appraisal, and splendid, full-color illustrations.

Anatsui has the sophistication of the true cosmopolitan, who can see beyond the limited vision of both art capitals and provinces. His work draws on his Ghanaian upbringing, his early academic and artistic education within European traditions, his self-study of African graphic systems, participation in Nigerian intellectual culture, overseas travels and ongoing reading of international art publications. One appeal of the book is the background Vogel provides about Anatsui’s work leading up to the metal hangings which brought the already mature artist to widespread notice over the past dozen years. She pays close attention to his technique, and has included a visual index of the vocabulary of forms Anatsui has fashioned out of the metal bottle caps that are the raw material of his monumental tapestries (which the artist considers to be sculptures). She describes how each form is achieved and the possibilities it contributes to the texture and form of the final work.

Vogel situates the artist within post-colonial African debates about art’s forms and functions, and points out the exceptional nature of Anatsui’s abstraction. She debunks simplified interpretations of the African origins of his work, situating him within international artistic concerns, and notes that his work conforms to African precedent most closely in erasing distinctions between art and craft and in its use of readily-available, everyday materials. Before being taken up by curators of contemporary art, Anatsui’s work was brought into Western art museums by curators of African art, among which Vogel numbers, having been the founding director of the Museum of African Art, New York. Anatsui himself said In 1990 in the Venice Biennale I showed as an African artist, a geographically defined artist. But 16 years after that, I went as just an artist. This book will interest anyone concerned with contemporary art, for its presentation and analysis of an important and singular body of work. It also gives an interesting, anthropological view of the Western art world, and a nuanced picture of an African artist negotiating both local and international demands.

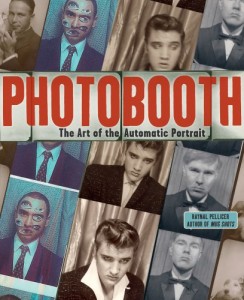

Raynal Pellicer Photobooth; The art of the automatic portrait (Abrams, New York: 2010) ISBN 978-0-8109-9611-3

The fact that many cell-phones have absorbed the function of cameras has had numerous unintended consequences. One is the disappearance of those small theaters of necessity and imagination, photobooths, which were once found in all train and bus stations. Presumably they were located for people in transit who might need photo identification, and their products satisfied the requirements of official, identity portraits. But photobooths also inspired play with the format, self-presentation and sequencing. They could accommodate multiple actors, costumes and props.

Anatol Josepho set up the first entirely-automatic photobooth in 1926 in New York City, and it was such a success that he sold rights to it in less than a year, for $1 million. By 1928 it was exported to Europe and Canada. Pellicer presents a pre-history and then history of the photobooth. He shows us the early equipment and its products. There are self-generated images of anonymous visitors to the 1933 Chicago World’s Fair and of New York Governor, Al Smith, as well as images of Samuel Beckett and Elvis Presley, among others.

Artists have made the most imaginative use of the photobooth, and Pellicer devotes much of the book to their work. In 1929 the Surrealists published an image in La Revolution Surrealist that included photobooth portraits of sixteen artists, including Breton, Ernst, Dali and Eluard, all with closed eyes. Andy Warhol’s direction of Ethel Scull’s photobooth performance, in 1963, yielded images which he turned into the monumental painting Ethel Scull 36 times, and Francis Bacon used photobooth images as studies for paintings. The book includes work by Al Hansen, Vito Acconci, Christian Boltanski, and many less well-known but equally adventurous artists. The illustrations make for an amusing eulogy to a once-common, photographic form.

Note: Photobooths are still around, largely available for rentals at weddings and private events, or use in artists’ workshops. A website is devoted to them, which includes an international locator for those still in public use. A quick glance found none in a bus or train station, but there is one, appropriately enough, at the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh.