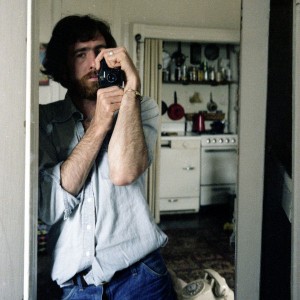

“It is highly ironic that I complain about my son’s use of technology when I stick a camera in his face.” –Ross McElwee

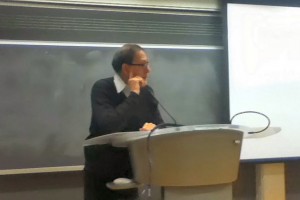

Lecture room 401 was packed Thursday, Nov. 8, for Ross McElwee’s screening and discussion of his latest film, Photographic Memory. Professors and film students filled most of the seats in Fisher-Bennet Hall at the University of Pennsylvania. They were clearly admirers and scholars of his work. Respected for his voice in the cinéma vérité movement, McElwee is known for opening his personal world in his films, incorporating home videos and reflective voice-overs and reflecting these familial narratives against historical parallels.

Photographic Memory focuses on the relationship between McElwee and, in his words, his “almost adult son, Adrian — and almost is the problem.” Far from a conventional exploration of father-son dynamics, McElwee seeks to understand his son’s standing in the world, with his eyes and camera lens acting as a filter through which to observe and reflect. A little bit worried and a great deal caring, McElwee reflects on where he was at 22, which sends him searching through old journals, photographs, and archived boxes of young adulthood.

Working for a brief stint as a wedding photographer in St. Quay-Porteiux, France, where he also had a youthful romance, McElwee decides to return to this beach town for a month, determined to see everything differently. In one shot, he tapes together a ripped map of France, full of hand-drawn circles around once-visited towns, emblematic of the reflection and purpose ahead. Between frequent Skype calls with Adrian from St. Quay, McElwee hunts down old acquaintances, once-visited settings, and farmers’ markets — oysters, postcards, and glasses of wine becoming objects brimming in nostalgia.

Wrapped within this father-son relationship is the generational divide largely created by technology. An analog pioneer, McElwee is still cautious of the digital world, fearful of memory cards’ memory — in contrast to Adrian, who spends most of his days sending text messages, watching YouTube videos, and editing his extreme skiing films. An aspiring filmmaker, Adrian is clearly trying to figure out an artistic path, while holding on to the freedoms and indulgences that living with your parents still provide.

By including some of Adrian’s film in Photographic Memory, McElwee adds another layer of exploration — observing Adrian’s way of looking at and reflecting on the world. In one scene — a shot of Adrian’s back to the camera as he looks out from a balcony — McElwee explains in voice-over, “Adrian relaxes and films himself relaxing.” Whereas the senior McElwee is often reflecting back, making greater comparisons to the world lived in, Adrian is still rooted almost exclusively in the present, his life the center-point.

Photographic Memory is beautiful, splendid in its subtleties and quiet in its profoundness. Technology, history, understanding, and time are brought together in unanswered narratives of raw human relation. McElwee’s voice-overs get to the heart of this rawness, his deep honesty and openness inviting viewers in. With a clear brilliance of narrative construction, the filmmaker challenges without causing strain, taking snippets of memories to create a solid, single memory of its own.

Underneath all of the seriousness is a great, and necessary layer of humor that reminds us of cinéma vérité’s engaging ability to reveal natural characters. Without much effort, chuckles passed through the audience throughout the film, responding to Adrian’s quips, to the the dry charm and adventurous spirt of Helene, (McElwee’s French ex-boss’ ex-wife), and to McElwee’s pointed jabs at his own young explorative ways.

As a newcomer to Ross McElwee’s film, I felt as though I had started a series with the last book (or film) rather than the first. That position was clear during the question and answer period that followed the screening. As one member of the audience pointed out, McElwee’s films and his characters (that are his family) are part of the collective memory of film-goers. Having seen Adrian’s birth and watched home-movies of him as a child in other McElwee films, that person saw Photographic Memory as particularly meaningful. In response, McElwee simply said, “I am painfully aware of that.”

Missing out on this collective memory could perhaps hinder a full understanding or appreciation of Photographic Memory. However, those who come to McElwee’s films backward, so to speak, are a new public, a generation of digital-minded viewers looking through the archive of one film-maker’s personal narratives.

The screening on Nov. 8 was presented in connection with Force Fields, an exhibit of documentary work curated by Jenny Jaskey and Alexis Granwell at Tiger Strikes Asteroid. Force Fields is up to Dec. 15.