by Virginia Maksymowicz and Blaise Tobia

Part 2: More Rome, on to Naples

The best part of visiting any city is wandering its streets; in Rome, of course, one expects chance encounters with marvelous churches, sculptural monuments, historic ruins and scavi (archeological excavations). But contemporary street art abounds as well. Some of it is obvious, such as the graffiti in the metro that transported us (as native New Yorkers) back to the 1980s of Lady Pink and DAZE. Some of it is subtle, like the small, black and white stickers of a man sporting sunglasses and a priest’s collar, stenciled with the words, “Why Not?” His face seemed awfully familiar . . . he turned out to be Jim Jones, mastermind of the 1978 mass suicide in Guyana. Some can be unconventional, like the two mosaics by Space Invader that we found— one of them right near the Vatican!

And some street art can be intriguingly elusive although in plain view. These works are part of the Sbagliato Project in which artists photograph architectural elements, print them actual scale, and surreptitiously adhere them to the sides of buildings. We searched but spotted only two of them, one already somewhat weather beaten. Sbagliato’s interventions have extended out from Rome to other Italian cities, as well as Amsterdam, Lisbon, Chicago and New York.

Near the Church of Santa Cecilia, hanging on a building with the enigmatic name, “The Central Institute for Cataloguing and Documentation,” we saw a banner announcing Corpi di Reato (Bodies of Crime) described as a photography exhibition about how the Mafia inserts itself into the fabric of society. Expecting to see the usual selection of documentary snapshots, we were instead surprised by large-scale, cooly postmodern, inkjet prints of places and objects by Alessandro Imbriaco e Tommaso Bonaventura. None of these seemed to have anything to do with organized crime . . . until we read the captions. For example, what appeared to be a quiet, residential street in suburban Milan turned out to be the location where police discovered two bazookas belonging to members of the ‘Ndrangheta (the Calabrian Mafia brand) who had planned to assassinate a local prosecutor.

The more conventional galleries for contemporary art were a disappointment. Magazzino on Via dei Prefetti was presenting “Hysterical Fantasy,” with work by Günter Brus, Jan Fabre, Sandra Vasquez del la Horra and Dennis Oppenheim. Despite the curator’s effort to link these artists together under the umbrella of “un-governable and frightening ‘self-darkness’,” the grouping lacked coherency. Frutta Gallery, a tiny space on Via della Vetrina, is directed by a very amiable Glaswegian named James Gardner. Unfortunately, the pieces in Nicholas Matranga’s solo show, “I only drive automatic,” did not even rise to the level of mediocrity.

The seven-artist group show at Federica Schiavo Gallery, Piazza di Montevecchio, entitled “FW2013RTW (Kudos),” was at least competent (Federico Proietti and Matteo Nasini are both worth mentioning). The multi-room gallery itself is beautiful. The most unusual space is that of Ex Elettrofonica on Vicolo Sant’Onofrio; it was designed by Alessandra Belia and Federico Bistolfi, who worked with architect Zaha Hadid. Artist Marco Raparelli, in his show, “Look Mommy I scribbled!,” used the space well, his humorous drawings peaking out as surprises from behind the turns and curves.

The last contemporary show we caught in Rome was Wu Weishan’s at the grand Palazzo Venezia. While it was obviously well funded with money from China (with lots of hype and free catalogues), there were some very competent bronzes on display. The introductory text was written by Fan Di’an, director of the National Art Museum of China and a visitor to Philadelphia in 2011, in connection with Drexel’s Chinese women artists’ show “Half the Sky.”

We stopped by Rome’s Academy of Fine Arts. Its high-school division was in the middle of a student strike and a crowd of parents was engaged in earnest debate with students blocking the doors. There have been major demonstrations all across Italy (and other EU countries) protesting government cuts in education budgets and scholarship funding. A few blocks away, Kim Strommen took us on a tour of Temple University’s Rome Center, where he has been Dean since 1991. Both the location (overlooking the Tiber River) and the facilities (in a building, the top floor of which houses a genuine principessa) are top quality. Many Tyler students have taken advantage of this great resource.

Although we spent much time seeking out “new” art in Rome, the “old” art is everywhere . . . and we saw lots of it. A very special experience was visiting the Pauline Chapel in the Vatican, where Michelangelo’s last frescoes (finished when he was seventy-five!) have recently been restored. Because it is not open to the public (being the Pope’s private space), it takes a good amount of letter writing and waiting before access may be granted. We spent nearly two hours with Dr. Marco Pratelli, from the Restoration Laboratory of the Vatican Museums. There are art historians who have considered these two frescoes (The Conversion of St. Paul and The Crucifixion of St. Peter) to be “lesser works” because of the apparent distortions in perspective as it appears in most reproductions: photographs usually shot from a front-center view. However, when viewed from the ends of the narrow chapel, as they should be, the “distortions” become resolved.

On to Naples

After Rome we headed south, spending several days in Naples. Our first afternoon, we took the Montesanto funicular up the hill to Castel Sant’Elmo and, by chance, found the Museo del Novecento (Museum of the 20th Century). Opened in 2010, it operates in a unique manner. It’s open Wednesday through Monday, from 10:00 am to 7:00 pm . . . but admission is only on the hour—exactly on the hour. We arrived about 10 minutes before five, along with three others. We could see a guard inside, his foot protruding slightly from behind a divider. We waited; the others didn’t. At the precise moment, the guard arose, came to the door and unlocked it. We entered and he locked it behind us! We had the museum to ourselves and saw a number of interesting works. Unfortunately, we were able to shoot only one photo, of a sculpture by Salvatore Cotugno, before we were told that cameras were not allowed.

As it had been everywhere in Italy, most of the contemporary artwork on display was by male artists. (This came as no surprise, of course. Remember the Guerrilla Girls poster, “It’s Even Worse in Europe”?) We were delighted, therefore, to see one room at the Novecento dedicated not just to women artists, but to the Italian feminist artists of Naples!

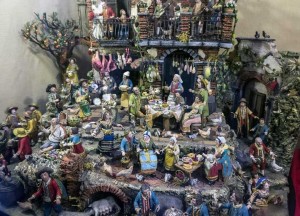

Where we did see the hand of women in ample quantity was in the folk arts. Naples is the center of what is known as the presepio, a kind of 3D nativity scene that not only includes the typical cast of characters (Jesus, Mary, Joseph, shepherds and kings), but entire towns and countryside. In the U.S., at Christmas time, one can see great examples of the presepio at both Chicago’s Carnegie Museum and New York’s Met. We saw a lovely exhibition of presepi at the former church of San Severo al Pendino. Two of the scenes depicted by women artists were highly unusual, one being the death of St. Joseph and the other being Mary babysitting not just her own child but an entire brood! As a typical Italian-surrealistic touch, the musical backdrop to this traditional display was Bing Crosby’s version of White Christmas (written by Irving Berlin)!

We had wandered into that exhibition because we had been trying to find the cappella (not the chiesa) of Sansevero (not San Severo) in order to see Giuseppe Sanmartino’s sculptural tour de force, Cristo Velato, along with works by other 18th-century sculptors, Antonio Corradini and Francesco Queirolo. The Prince of Sansevero, Raimondo di Sangro, who built this extraordinary chapel, was in Wikipedia’s words, “an Italian nobleman, inventor, soldier, writer and scientist.”

In his time, he had also gained the reputation of being a mago (sorcerer). Photographs were not allowed, and the books on sale were horribly printed, but there is a great website.

Before we left Naples, we were also able to see another compianto, that of Guido Mazzoni, at the Chiesa di Sant’Anna dei Lombardi. This hyper-realistic, life-size grouping sculpted in clay was a sight to behold. Again photographs were forbidden and there wasn’t even a postcard to buy. However, we spent nearly an hour speaking with the church’s custodian, Stefano Deda. Although he was insistent that he is not an “expert,” this man has spent most of his waking hours in the company of not only the Mazzoni, but of Giorgio Vasari’s spectacular frescoes on the ceiling of the refectory. This amazing complex is little known and has no budget for promotion, but is well worth a visit, especially if Stefano is around.

[Ed. note: Look for Part 3 of this report later this week.]