by Virginia Maksymowicz and Blaise Tobia

Part 1: Verona, Milan, Padua and Rome

We spent the months of November and December traveling through Italy in connection with Blaise’s new photo project and Virginia’s sabbatical research leave. We’ve visited Italy nearly a dozen times now, and speak the language reasonably well. We’ve also learned an important lesson: in order to fully experience this country, one must not overplan the day. Galleries that should be open might be closed. Museums that should be closed, might let you in if you knock. Appointments to meet people may fall through, but chance encounters can often prove to be more interesting and lead to other opportunities. Websites may or may not be accurate; it’s more likely that you’ll get the best information from a conversation or a randomly posted flyer.

We began this trip in Verona, where we had just missed ArtVerona, one of those expansive international art fairs. We couldn’t see the Galleria d’Arte Moderna housed in the Palazzo Forti because it was in the process of relocating to the Palazzo della Ragione. However, we did visit the Museo del Castelvecchio, the primary historical art museum, which is a delight. We also saw two photography shows of interest. Ironically, since we had just spent several weeks in China, we found ourselves at the opening reception for “China’s Long March into the 20th Century” at the Palazzo della Gran Guardia. The photographs reproduced in the exhibition (there were no actual vintage prints) traced the history of China from 1842 to the present day; some of the contemporary ones were by David Turnley. We also saw “NeoRealism: the new image in Italy 1932-1960” at the Centro Internazionale di Fotografia, which compared the work of documentary photographers with Italy’s emerging cinema.

An unusual diversion was the time we spent climbing through towers at the Verona Cathedral and the Church of Sant’Anastasia with a group of volunteer bell ringers (campanari) from a school where the traditional form of Veronese ringing continues to be taught. These bells are marvelous sculptural objects in themselves and the nighttime views from the towers were fabulous. During a concerto (ringing based upon a musical score), the sound from within the tower is unforgettable.

We traveled to Milan for a weekend in the hope of checking out the contemporary art scene. We tried to find Lia Rumma Gallery but the Artnews.org website had indicated the wrong location on their map. Suzy Shammah and Cardi, whose websites and front doors indicated that they would be open, were inexplicably closed. We did, eventually, unravel the mystery. The previous Thursday had been All Saints’ Day, a national holiday in Italy. The galleries had decided to do what Italians call a ponte (i.e. bridge), and extend the holiday into a five-day weekend! If we had been locals, we would have known.

A spectacular Milanese venue for contemporary art is the Fondazione Stelline, just around the corner from the Cenacolo (site of Leonardo’s Last Supper). It houses several galleries, a bookstore, a permanent collection including paintings by the “Three C’s,” a central courtyard sculpture garden and an affordable (and very good) trattoria. We saw an installation of neon tubing, Dreams of a Possible City by Massimo Uberti, hovering above the courtyard.

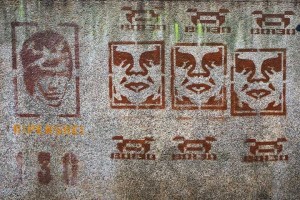

We passed on the blockbuster Picasso show at the Palazzo Reale, partly due to a very long queue, and decided instead to wander the streets, where we encountered some delightful stencils. We’re not sure if Shepard Fairey was responsible for any of them, but André showed his face anyway!

A day in Padua did not unearth any interesting new art. (Although we learned that Arte Padova was about to open, the printed guide we saw didn’t convince us to come back.) The old art, however, was outstanding! We had an appointment to see the restored Giotto frescoes at the Scrovegni Chapel; reservations are now necessary in order to limit the number of visitors and prevent further damage. Before entering the chapel, we visitors were led into an anteroom ostensibly to view a video. The hidden agenda was to dry us all out so that we would bring the minimum amount of humidity into the chapel. Visits are limited to twenty minutes but, if the next group isn’t full, and you ask nicely, the guards may let you stay for another twenty.

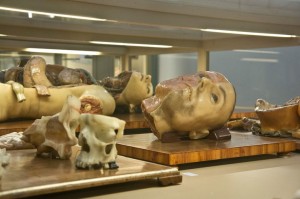

A trip to Bologna rewarded us with some beautiful street art and a sampling of great old masters. We were surprised to discover that the Pinacoteca Nazionale—the primary historical art museum—allowed us free entry when we told them that we were professors of art (we always ask, but we are usually not even offered a discount!). A spectacular part of our visit was seeing several examples of a sculptural form called a compianto—a highly realistic group of life-size terracotta figures in lament around the dead Jesus. This was a medieval specialty in the Bologna region. The ones by Alfonso Lombardi at the Metropolitan Church of San Pietro and by Niccolò dell’Arca at the Church of Santa Maria della Vita are astonishing. These works, which can be seen as antecedents of both Rodin’s Burghers of Calais and contemporary installation art, deserve more attention than they have received in the art history texts. To see the Lombardi, we had to find the custodian to turn on the lights for us, since the coin-operated light machine was out of order. The dell’Arca was still underneath scaffolding to protect it from aftereffects of last May’s earthquake. Continuing on a hyper-realistic sculpture theme, we scouted out the wonderfully peculiar Museo delle Cere Anatomiche L. Cattaneo, an historic collection of highly detailed anatomical wax models that easily compete with anything at the Mütter Museum in Philadelphia. It’s housed at the University of Bologna; for figurative artists, or just the curious, it is definitely worth a side-trip.

Once again, our attempt to see contemporary art was thwarted. We had planned to go to the MAMbo (Museo d’Arte Moderna di Bologna) on our final day, but an impending railroad sciopero (i.e. work action) forced us to flee town about an hour before it opened.

After our time up north, we headed to Rome, where we spent two weeks as Visiting Artists at the American Academy. It is truly a magical place, located at the top of the Janiculum Hill, its main building having been designed by McKim, Mead and White (architects of the Brooklyn Museum). It is a center for artists and scholars to conduct research and to exchange ideas . We met the current Rome Prize recipients in visual arts: Nari Ward, Glendalys Medina, Carl D’Alvia and Polly Apfelbaum, whom some of you might remember from Tyler where she received her BFA in 1978. (Past winners in visual arts from Philadelphia have included Josh Mosely, Terry Adkins, Joel Katz and John Schlesinger among others.)

Perhaps the major art-related change in Rome during the past decade has been the increased exposure for contemporary art. Previously, independently run galleries were few and far between, and contemporary work was only rarely featured at the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna. But now there are two major contemporary museums: the MACRO and the MAXXI.

The MACRO (Museum of Contemporary Art of Rome) officially opened in 2002, but it gained a much higher profile in 2010 after a major expansion designed by Odile Decq & Benoit Cornette (the original building had been a Peroni Beer brewery). There were three main exhibitions on view: “Portrait of a City: Art in Rome 1960- 2001” (weak on artwork but good on history); a large installation of sculpture by Cameroon artist Pascale Marthine Tayou, “Secret Garden” (a group of folk-art figures on classical columns was terrific); and a retrospective by an old acquaintance of ours, American artist Jimmie Durham. For us, the best part of his “Streets of Rome and Other Stories” was the documentary video of his performance Smashing, a hilarious send-up of Italian bureaucracy.

The MACRO has a second location, consisting of two pavilions at a massive complex originally built as a state-of-the-art slaughterhouse in the neighborhood of Testaccio. While exhibitions have been occurring there since 2003, the space is still a work in progress with one pavilion lacking climate control and adequate lighting. But the MACRO Testaccio is an exciting and gracious cultural center in an area that is Rome’s equivalent of Long Island City. When we visited, the Starn Twins and their climbing crew were just finishing a towering outdoor sculpture,

Big Bambú, similar to, but taller than, an earlier version they did at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. We were invited to come back that night for a “bambú party” and a climb to the top.

The major show at the MACRO Testaccio was “Digital Life 2012 – Human Connections,” additional parts of which were presented in two other venues: at the “ex-Gil” in Trastevere (a former center for Fascist youth) and at the Opificio Telecom Italia (a multi-purpose exhibit space). Another show, “Lo Zuavo Scomparso,” included photographs by Paolo Ventura. We had previously seen his work at Hasted Kraeutler on West 24th Street in Chelsea and thought it unsettling and evocative.

Testaccio itself has a long and vibrant history stretching back to ancient Rome, when it was the receiving port for huge quantities of provisions shipped up the Tiber River. Its most visible feature, a large hill called Monte Testaccio, is actually man-made. For centuries, it was the dumpsite for the ceramic shards of the amphorae used to transport oil. As large as the monte is, archeologists estimate that it was about 50% bigger at the time of Rome’s fall. Modern Testaccio was built as a model neighborhood for workers in the late 1800s. Unfortunately for the working class, it’s now being gentrified because of its very livable and relatively affordable residences, its good location, and the “hip” character being added by the MACRO and other cultural institutions.

(Tutto il mondo è paese – It’s the same everywhere.)

The MAXXI (Museum of the Art of the 21st Century) opened to great fanfare in the spring of 2010 with a huge signature building designed by Zaha Hadid. We were greeted at the door by a gigantic synthetic raffia sculpture, Maloca, by the Brazilian designers Fernando and Humberto Campana. On entering, we found ourselves in the midst of an intriguing performance in the lobby—a dance of everyday people in everyday motion entitled I live by long distance, by a group called L’Associazione Orma Fluens. Upstairs, William Kentridge’s solo show, “Vertical Thinking,” had just opened. Its centerpiece was the masterful installation, The Refusal of Time, previously shown at Documenta 13 in Kassel, Germany.

Unfortunately, the MAXXI is facing significant financial challenges after just two years of operation and we heard many rumors of possible closure, although the museum disputes this.

Given the inscrutability of Italian politics and the current economic crisis in the European Union, we wouldn’t take any bets. In fact, the effects of the current economic and political crisis were so evident all over the country that nothing about the future of the cultural scene in Italy should be taken for granted.

Parts 2 and 3 of this report from Italy will be published next week.

–Virginia Maksymowicz is a sculptor and teaches in the Art & Art History Department at Franklin & Marshall College. Recent exhibitions have been at the Delaware Center for Creative Arts in Wilmington and BronxArtSpace in NYC.

–Blaise Tobia is a fine art photographer, teaching in the Art & Art History Department at Drexel University. He is looking forward to an exhibition at O.K. Harris Gallery in NYC in June, 2013.

Their joint website is at tandm.us. And their last report for artblog was in Oct, 2012, when they told us about their trip to China.