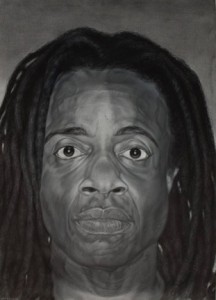

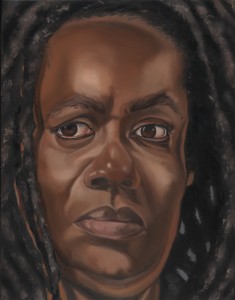

Diane Edison’s two arresting pastel self portraits, in the exhibition “The Female Gaze: Women Artists Making Their World,” sample from the artist’s impressively detailed and stirring portraiture. Edison, a professor of art at University of Georgia, is also an incredibly charismatic individual, as I learned from her artist’s talk February 2 at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. In the introduction to her talk, Edison‘s works were called “two of the most talked about portraits in the exhibition.”

Pastel on black paper; 44 x 30 inches

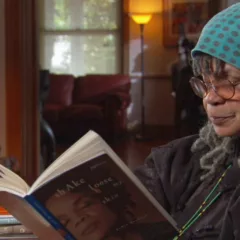

The artist’s talk was a light-hearted journey through the history and progression of her work, starting with her early painting and rich colorful pastel drawing (the two portraits in the show fit into this early category) and ending with the transition into her most recent body of greyscale colored pencil drawings on black paper.

Color pencil on paper; 44 x 30 inches

She opened the talk with what is easily one of the most striking self-portraits in the show, a nude in which she gazes down at the viewer with an incredible intensity, as if saying “What you see is what you get.” Edison debunked the assumption of confrontational intent, explaining that she was not angry or trying to be aggressive but that the work was actually spawned from the initial desire to feel vulnerable.

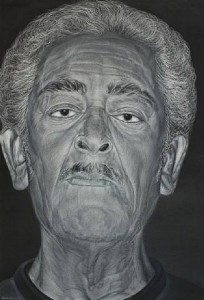

She went on to discuss several works her 2007 exhibition “The Men In My Life,” which was begun in the same spirit as the “The Female Gaze” exhibition as a whole, that is, to increase visibility and awareness of women in art. The works from “The Men in My Life” were made to bring attention to the fact that men simply have shows while women have women’s work, the artist said. Describing the portrait of her father, Anthony Francis Edison, as the appropriate start in this series of male portraits, the artist said she and her father had an “interesting, to say the least, relationship.” The portrait projects a sense of defiance but it is impossible to say whether Mr. Edison is looking down at Diane, or she is looking up at him. He was 92 when she drew him.

Colored pencil on paper; 44 X 30 inches

Edison brought us through the process of many of her portraits, most of which are drawn from black and white photographs. She chooses friends, family and co-workers as subjects for her portraits and many of the stories behind these works are particularly charming and personal. Some of the most revealing of these include the portrait of her father, her daughter, fellow artist Luis Cruz Azaceta and, of course, herself.

The commanding portrait of her daughter Rebecca at 14 embodies a potent yet indescribable feeling that almost any woman can relate to, as a mother or as a daughter; a look of engagement which Diane describes as a struggle. Her daughter is now 18, and “College looms ahead,” she said.

Color pencil on black paper; 44 x 30 inches

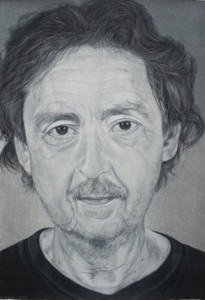

Describing her experience in drawing fellow artist Luis Cruz Acaceta, Edison said the drawing came about abnormally quickly. She completed it in four days as opposed to the average three- to four-weeks. This quick drawing evolved because unlike her normal portrait drawings, in which she often feels like her drawing requires asking permission to capture a person, Cruz Acaceta seemed immediately willing to “let her in.”

Color pencil on paper; 44 x 30 inches

With much humor and grace, Diane Edison allowed us in to her world as an artist, woman, mother, daughter and teacher. Her demeanor was enchanting and her work emotional. Her intricate portraiture invites her audience to experience her personal relationships and skillfully reveals her intimate perspective.

Diane Edison’s work, like all of the self-portraiture in The Female Gaze, gives the audience tools to better understand art and the artist through the lens of womanhood and individuality and the extra push needed to begin utilizing them.

“The Female Gaze: Women Artists Making Their World, until April, 2013. Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. Fisher Brooks and Annenberg Galleries, Samuel M.V. Hamilton Building,128 N. Broad Street.