Four Houses, Some Buildings and Other Spaces, an exhibition curated by Berta Sichel at NYU’s 80 WSE Gallery through March 16 brings together ten artists (or artists-collaborations) around the ideals and memories invested in buildings, other man-made structures, and their remains. They investigate the subjects of who determines the built environment, who establishes its meaning, who tells its history, and which of multiple histories are preserved. The story they tell is complex, nuanced and provocative, without being tendentious.

The artists, from Europe, North and South America, are primarily interested in buildings as bearers of ideas – either those of their architects, patrons, the people who used them, or people in the present who value them for a variety of reasons. Some of the artists conduct an archaeology of vernacular structures and material culture, adopting the perspective of history from the bottom up (of the Annales School, E.P.Thompson, Howard Zinn, et al). Others look at the intersection between money, power, and buildings.

The brooding, night-time photographs of Esteban Pastorino Diaz document the remains of the monumental, symbolically-infused architecture of Francesco Salome in late 1930s Argentina. The extravagant, Art Deco structures with bold, geometric embellishment, look more like stage sets than actual buildings, and reflect some of the utopian interest in geometry of Boulee and Ledoux. But Pastorino Diaz was interested in the ambitions of the conservative government behind the structures, and their abandonment as a metaphor of political failure. Nina Fischer and Maroan El Sani’s 2-channel video installation, Spelling Dystopia (2009) is a complex document of Hashima, a small, man-made island off the coast of Japan. It was built in the early 20th century to house coal-miners and subsequently housed forced Chinese and Korean mine laborers. Hashima’s concrete apartment buildings at one time contained some of the densest populations in the world. Their crumbling remains have been used as a site for films about James Bond and others, and their ruins have been proposed as a World Heritage Site. The scenes include the final high school class in formation, spelling out sayonara Hashima, while multiple voices recount experiences of living on the island and knowledge of the island acquired from text-books and legend.

Terry Berkowitz focuses on structures arising from conflict. Walls Without End (2005/2012) proposes fragments of four politically-generated walls as memorial artifacts, each with an engraved wall plaque: the wall separating Palestine from Israel, the Berlin Wall, the Berm built by Morocco in the Western Sahara, and the wall surrounding the Warsaw Ghetto. While the work could be ironic, it also serves to ward off repressed memory. Barriers and Beyond (2007), a video by Berkowitz with Varsha Nair and Karla Sachse, explores an international group of military bunkers and barrier walls and their impact on the surrounding populations.

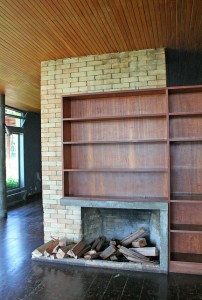

Bernhard Leitner documents his single-handed campaign to save the Wittgenstein House in Vienna. As one scholar described it, the house is the only significant work of art produced by a major, 20th-century philosopher, and Leitner’s battle involved not only establishing its authorship, but fighting the inevitable interests of money, local politics, and urban development. His narrative is supported with extensive documentation of his correspondence and publications throughout the process, and a video interview. Ines Lombardi has created a poetic exploration of the current, degraded condition of an exemplary house designed as a machine for living, one that embodied European utopian ideas transplanted to the climate of coastal Brazil. Her work employs architectural walls, video and a book documenting the present condition of the house that Rino Levi designed for Olivo Gomes in the 1950s. She considers the house’s original design, the effects of time and nature, and the ongoing use of abstraction in Brazilian art and architecture as an expression of social aspirations.

Additional work in the exhibit at 80WSE is by Lara Almarcegui, Peter Downsbrough, Terrence Gower, Leandro Lattes and Carlos Schwartz. The show is up until March 16.

Orhan Pamuk The Innocence of Objects; The Museum of Innocence, Istanbul (Abrams, 2012) ISBN 978-1-4197-0456-7

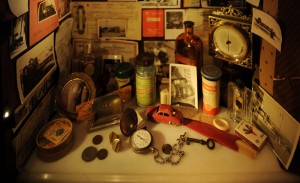

Orhan Pamuk interweaves his own salvage archaeology of the material culture of post-Ottoman Istanbul with the fictional characters of his novel, The Museum of Innocence in this un-classifiable book. It will appeal to those who love old things and the stories they tell, who think of flea markets as treasure trove. Every old magazine stored in a closet, each broken watch languishing in a dresser drawer and dis-used household object in a local junk shop, is a madeleine for Pamuk, evoking memories of the Istanbul of his youth (and that of his characters). This was the city of the educated, Westernized, upper middle class – a side of Istanbul which is rapidly fading in the face of increasing Islamicization.

Pamuk has actually created the cabinet of memories he calls The Museum of Innocence, in Istanbul. Each of its 83 cases (one corresponding to each chapter of his novel) contains an arrangement of the out-dated, broken, disfunctional, and cast-off remnants of everyday life, brought together by Pamuk’s rescue operation, his obsessive accumulations. The museum is in a class by itself, in being based upon a novel. The book has wonderful (and I do mean evoking wonder) illustrations of its artfully-assembled vitrines, classified with a logic that parallels Borghes’ Chinese encyclopedia (Those that belong to the emperor, Embalmed ones, Those that are trained, Suckling pigs, Mermaids (or Sirens)…).

The series of vignettes that constitute The Innocence of Objects is a meditation on the meaning we attach to objects, and the unexplored information they contain. Pamuk employs the fiction writer’s liberty to invent, with the real objects, structures and connections he discerns in the world. But his major focus is people, and he uses things, in addition to words, as a means to tell the stories of individual lives.