Three photographers who won the 86th Annual Photography Competition at the The Print Center each currently has their own solo show at the Center. The works by Talia Greene, Jennifer Greenburg and Anne Massoni share interesting and unintended similarities: they all utilize found, black-and-white photography and combine the photos with contemporary technologies and thinking to ultimately purvey an eerie timeless aura.

Talia Greene converted the first floor of The Print Center into a beehive. For apiphobic- or melissophobic-viewers (afraid of bees), this installation could be a horrifying experience. The honeycomb wallpaper Greene created digitally is made up of tiny images of stems, hair and insect parts. The same minimalist elements make up the bodies of the countless bees roving over the walls of the room, crawling out of a heating vent in one corner and massing in great crowds in other areas. The high-pitched whine of electricity from the walls feels like the buzz of bees working to build a hive on the walls.

The hexagonal honey-comb pattern that dominates most of the walls contradicts another pattern that tesselates elsewhere. These patterns, which reflect Western and Arabic architectural and design sensibilities, play off each other as polar opposites, while the bees working are all but indistinguishable from one another.

The beehive installation also impacts the viewer like a living room one is welcomed into. Found photographs on the walls show people and a building that have been digitally altered to cover the subjects with swarms of bees. The insect life that covers and seems to create all the objects in this installation does not clearly correspond to any real-life force, instead acting like an imaginary sub-atomic particle that forms matter and holds it together. From a strictly design perspective, the Cross Pollination project is hypnotic. But in terms of the meaning of cross-pollination, this installation suggests an activity performed by an insect on an unsuspecting, inanimate human world. It is less fertilizing than suggestive of the conquest of civilization by nature.

Jennifer Greenburg’s show, “Revising History,” includes work from a series of “counterfeit images that depict fictitious memories,” as she describes them in her artist’s statement. The photographs show Greenberg herself smiling widely in photographs of the 1950s to which she has been transplanted using digital technology. While her process and technique is a trade secret, assistant director of The Print Center Ashley Peel Pinkham assured me that Greenberg doesn’t just lop off heads of original people and copy-and-paste her own face into the photos. She works intimately with negatives, placing the image of herself in the middle of the action. Much of the impact of these pieces comes from awe at the seamlessness with which the artist has added herself to these moments.

The works combine the theatricality of Cindy Sherman’s work with genuine nostalgia for the ‘50s – Greenburg also has a set called “Rockabilly,” which celebrates the alternate lifestyle of modern-day Luddites known as “Rockabillies” who forgo modern technology, clothing and fashion in favor of that of the 1950s. But the series is also darkly tinged by the artificial afterlife of the subjects in these photos, enlisted in Greenburg’s work without their permission. It’s all a bit reminiscent of the final moment of Stanley Kubrick film “The Shining,” when Jack Nicholson is shown smiling demonically in a photograph from decades before his character was even born.

Greenburg is smiling happily in most of these photos as she participates in the dead and frozen moments she has found. She clearly identifies with the random strangers who she sees in these negatives; and it’s almost like these images explore the transference of sense of self to a decades-old photograph of strangers. By seeing lives in the past similar to hers, the artist sees some sort of reflection of herself.

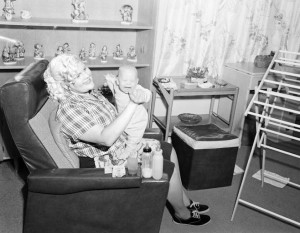

Fifties middle-class social mores exist at the fringes of these photographs. The people portrayed seem to feel satisfied with life in this black-and-white world, but the photos also demonstrate some alarming tendencies of the past. In “When he was a baby,” Greenberg has a pack of cigarettes next to a bottle of milk. Probably my favorite photograph here is “My Funeral,” when Greenburg closes the loop with the images of the distant past and puts herself into a casket, surrounded by flowers in an old church auditorium.

Anne Massoni’s show, “Holding,” includes selections from the artist’s three different “Holding” series of paired images, each of which is named after a person who played a role in the artist’s life. According to Massoni’s statement, this series pairs “photographs I’ve made of empty spaces… with found photographs of times that no longer exist…” The photo pairs are united by a hand-drawn or painted line on the surface that connects them.

But what is the artist holding onto? The ties in each photo (the lines on the surface connecting the images) are like a stitch between memories, with each point a coordinate on a map. The human senses are often one point on the line — the mouth, ear, or hand of a figure; the other point being a blank, random space or endpoint – water, land or other object. Many of these “holds” are ties between a human temporal moment and a depiction of the eternal inanimate.

Connecting the living past with more existential moments frozen in photograph form, these photographic pairs both preserve the found image and join it to the decaying, destroying forces of time. They represent a duality between the clear interest in preserving and holding on to the moments and the emotionless onslaught of the inanimate.

Through Greenburg’s black-and-white 1950s world, Greene’s feverish honey-comb spinning, and Massoni’s juxtapositions of visions, each of these three artists’ works gives off an enticing aura that welcomes the viewer into her world. The combination of exploration in the process of remembering and seeing is a venture in which all of these artists seem to take part.

The works of Greene, Greenburg and Massoni will be up through March 16. For more information, visit www.printcenter.org.