By pairing two artists who couldn’t be more dissimilar — Rebecca Reeves and Gregory Coates — The Soft Machine Gallery‘s Eva Di Orio provokes discussion of permission, control, property and ownership, specifically by focusing on the tangible nature of these subjects. The Allentown gallery is enjoying its third month in its giant new industrial space.

photo credit: John Mortensen

photo credit: John Mortensen

Opening night, goose down from Coates’s installation “Stage” had drifted into the hallways, blurring the boundary between his room and the other artist’s. The shiny bits of animal beauty crushed under winter boots signaled that his newly-installed sculpture was already beginning to decay. Rebecca Reeves’s show, titled “Through That Which Is Seen” was something quite different — sculptures of miniature furniture tightly-sewn onto squares of industrial felt; shiny, framed cyanotypes, and drawings. I left the gallery, mulling over the two radically different perspectives: Coates’s lighter, relaxed, engaging nod to entropy against Reeves’ obsessive control over personal objects.

Rubber, Feather, dimensions variable.

photo credit: John Mortensen

Coates is the first of what I hope will be many artists that exploit the cathedral-high ceiling in the gallery’s back room. He hangs a waterfall of recycled, tied-together bicycle inner tubes from a discarded and re-purposed trellis, allowing the tubes to cascade down onto an inviting carpet of fluffy, white-and-cream-colored feathers. Coates demonstrated how to walk in the feathers: “Slow . . . watch your step,” like a big brother after a pillow fight. Austere and airy, the piece works with time and space by limiting the information I am taking in and making me slow down and walk with both care and pleasure. I imagine rising up like a balloon through the crusty, snaky coils of rubber to bob around freely, yet my feet are still firmly grounded.

“Stage” invites our participation—just take that step over the lip that corrals the feathers and you’re in. And on February 23 dancer Aya Iida will perform in the installation as part of “Lollipop,” a celebration of Osaka artists in Allentown put together by FUSE art infrastructure. Coates made it clear that Aya Iida will have complete freedom to do whatever she likes that night: permission is integral to the piece. (The Lollipop festival is hosting approximately 30 Japanese artists while they are in the U.S. for the Gutai: Splendid Playground show at the Guggenheim Museum in New York this February.)

Since traveling to Japan in the mid 2000s, Coates’s work has been influenced by the Japanese aesthetic movement known as Gutai, which is considered a collective response to the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1944. Gutai translates as “embodiment”: literally, Gu means “tool” and tai means “body.” Sensation, physical action and psychological freedom arrive with Gutai through experimenting with unexpected materials and through breaking with tradition. In the Gutai Manifesto, Jiro Yoshihara, the movement’s founder, states: “Novel beauty is to be found in works of art and architecture of the past which changed their appearances due to the damage of time or destruction by disasters.” Gutai, which values “the beauty of decay,” asserts that objects need to have the surface “make-up” removed, meaning, therefore, that traditional art-material application loads on “false significance.” Gutai was a precursor to Art Informel in France and the Fluxus movement here in the U.S in the 60s. Today, it would be considered Installation Art.

“Family Preservation (Dining Room)” Miniature Furniture,” 2012,

Thread, Industrial Felt ,

16.5″ x 20.5″

photo credit: Jason Wierzbicki

Where Yoshihara sought a “tremendous scream in the material itself,” Rebecca Reeves’s sculptures of miniature furniture sewn onto slabs of industrial felt scream control, and they make me feel as bound as the objects I’m looking at. In an email, the artist describes herself as the “Collector, Protector and Keeper” of numerous family heirlooms and antiques that have been passed down through three generations. Her determination to keep this primary collection safe, dust-free and organized overflows into creating meticulous secondary sculptures, drawings and prints; yet, fortunately, her seriousness can suddenly switch to humor.

I relish her photos of miniature chairs, chests, and tables fitted with carefully sewn clear-plastic dust protectors (!). Not stopping there, she made an even bigger cover for the entire collection. Laurie Simmons’s doll furniture photographs come to mind, but Rebecca seems to work in isolation from art world references, with tunnel vision for her clear, singular purpose: maintaining control over her personal possessions.

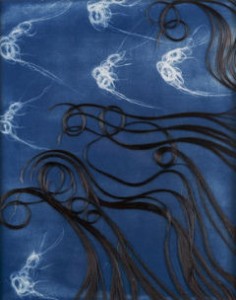

“Photophore W.C. no.01” , 2011-2012

Cyanotype Print, Human Hair, Layered Plexiglas

photo credit: Jason Wierzbicki

22″ x 18″

Drawings made from photos of hairballs found in her bathtub and shower drain explore the sinister nature of hair, a dead extension of the body, running counter to Reeves’s need for order and cleanliness. I will be interested to see how her work with hair develops. To quote Yoshihara: “Art as we know up to now [is] fakes fitted out with tremendous affection,” so from the Gutai point of view, Rebecca’s use of non-traditional materials saves her from being hamstrung by a love of control.

The show presents two contrasting temperaments: Gregory Coates shares space, grants permission, and holds his own by relaxing control, while Rebecca Reeves guards against decay, dust and chaos, against which, for the moment, she is winning.