At a session of the College Art Association annual meeting in February (On the Social, The Relational, and the Participatory…), Martha Rosler spoke about her initial garage sale in 1973, at the gallery of the Visual Arts Department at the University of California, San Diego, and the many sales she has held since then at art venues in the U.S. and Europe. She showed images of the recent sale, held in the atrium of the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA, Nov. 17-30, 2012), which she said was her last. She remarked that it received international press attention, but there was no attempt at a critical evaluation of the event. None.

After Rosler’s first Monumental Garage Sale in 1973, Sandy Dijkstra, wrote: Somehow Rosler’s ‘Garage Sale,’… fails. It is nothing more than the thing it is and although the intention may have been to represent life in Southern California, or America, any critical dimension seems to be blunted by an overwhelming sense of suffocation in what it was. It was a real garage sale; Forty years later, the artist comments her [Dijkstra’s] essay complains of the show’s failure as a consequence of her ‘overwhelming sense of suffocation in what it was.’ Only if one subscribes to the view of art as beauteous and ennobling could such a reaction be taken as a measure of failure rather than one of success (both quotes from Rosler’s Meta Monumental Garage Sale Standard, Issue 2, p. 14, the second of two tabloids given away during the sale at MoMA, and available as a pdf.

I attended the Meta Monumental Garage Sale at MoMA with an artist friend. We weren’t serious shoppers and didn’t buy anything. I thought about purchasing something, anything, as a souvenir of the event. Since the artist considers her sales to be performances (it was organized by the Department of Performance and Media Art), would items purchased at the sale be considered art? Might they acquire that value in the future? Chris Burden exhibits relics of his performances, one of which is in MoMA’s collection (Icarus, 1973; oddly, in the Department of Painting and Sculpture). The museum accessioned the still-intact fragment of Tinguely’s self-destructing Homage to New York (1960), an artifact of its partial failure that I wouldn’t think the artist considered to be art. My meta musing made me realize that I may have passed up a monumental bargain.

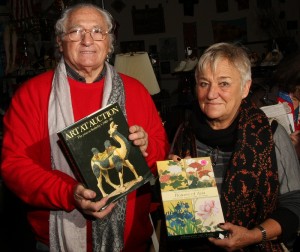

My friend and I noted the irony of racks of used clothing and arrays of tchotchkes for sale in the atrium of MoMA, whose display conventions became the paradigm of the gallery as white cube, even if this particular white cube was underwritten by Rockefellers and their ilk. We could barely discern Rosler’s sound track (readings from economic theory, according to the literature) over the noise of the shoppers, who behaved much as they would at any garage or jumble sale, and we could not understand the text. Rosler and the museum produced two, free tabloids which give some critical and historical frame for the sale. They include an interview of the artist by the curator, a discussion about garage sales with an anthropologist, a sociologist on the concept of ethical consumerism, statistics on domestic labor, a number of literary excerpts (Kafka, Edith Wharton, Flaubert et al) which discuss domestic possessions and their sale as second-hand goods, and a geographer on the geopolitics of work, value and waste. The dedicated Garage Sale website has extensive photos, taken by a professional wedding photographer, of happy purchasers holding up their finds and looking very much like the smiling participants on the Antiques Roadshow who display their newly-appraised possessions. But the artist said all she heard was complaints. The complainants certainly accepted the sale for what it was.

I was clearly a minority visitor, unable to participate in the spirit of the sale because forty years after Dijkstra declared that Rosler’s Garage Sale was a real garage sale, for me it was now unquestionably art. And I wondered whether it was possible, in the twenty-first-century Museum of Modern Art, for Rosler’s garage sale to trouble participants with the questions of value, exchange, commodity fetishism, women’s roles and home economics that prompted its earlier iterations? At the twenty-first century Museum of Modern Art the white cube, which ostensibly isolates the art within from politics, economics, and other sordid necessities of daily life, has lost much of its premiss.

Prices and sales values permeate MoMA, every square foot of which has clearly been monetized. Everyone attending the sale had paid $25 just to enter the museum. The sale was held is one of those spaces that have become standard in all museums built during the past several decades. It was designed not only for the museum’s own entertaining, but also to produce rental income. The museum’s website says it can accommodate 400 for dinner, 700 for a reception. A few feet from Rosler’s sale was MoMA’s bookstore, the vestige of its former self which used to carry a serious selection of recent literature on modern and contemporary art. I did research for a book in the old store, since much of the stock had yet to be acquired, cataloged and placed on library shelves. It is obvious that the museum allocated space for the current bookstore on the basis of estimated sales per square foot. And the more modest of MoMA’s two restaurants, run by an outside firm which presumably pays well for the privilege, no longer offers food that artists and students can afford, if one uses the standard that lunch cost no more than an art handler makes per hour.

Museum visitors have their own standards. In order to see MoMA’s modernist collection at the moment, all but members (who pay at least $85 annually) must wait in line with the crowds attracted by the temporary loan of a version of Edvard Munch’s The Scream. The Munch has its own, peculiar allure, as the many inflatable, plastic versions and other, humorous variants attest. But surely its market value is part of the fascination with the work currently on view. It was bought, anonymously, at auction last May for the widely-publicized price of $119,922,500. It is the only work at the museum with such a recent, public appraisal.

It is worth remembering that most art in most museums is out of its native habitat, whether that was a church, civic building, palace or bourgeois home. The only parts of museum collections that can be said to be on home ground are certain very large works, primarily made after World War II. Dieter Roth’s Solo Scenes (1996-98), on view a gallery away from Rosler’s sale, is exemplary: 131 video monitors arranged in a grid, with footage of the artist’s everyday life during his two, final years. Installations, in general, are museum pieces, whether they find homes there or not.

Museums operate under the fiction that their collections have no market value – because they will not be sold. The accounting profession has finally gone along with this, so that under Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP), collections are not capitalized in museum budgets. And in order to keep the boards from treating collections as contingency funds, museum ethics (and the U.S. tax code) stipulate that money raised from sales from collections – deaccessioning – must go back into the collections. Museum practice further dictates that all objects in the collection are handled with the same care, regardless of potential market value.

Museum curators are generally an acquisitive lot. They would like to bring all of art history within the institution’s compass. And artists, at least since Duchamp, have had conflicted attitudes toward museums, despite the fact that Duchamp spent the last twenty years of his life working in secret on an installation which he donated to the Philadelphia Museum of Art. In 1970 Daniel Buren expressed one extreme position: The Museum not only preserves and therefore perpetrates, but also collects. The aesthetic role of the museum is thus enhanced since it becomes the single viewpoint (cultural and visual) from which works can be considered, an enclosure where art is born and buried, crushed by the very frame which presents and constitutes it.

Rosler has held all of her garage sales in art institutions of one sort or another, so I assume that at least part of her intended audience is the art community. Her work is not primarily institutional critique, except on the most meta of levels, lest anyone forget that art is embedded in commerce, which makes the world, or at least the part in which museums participate, go ‘round. That message, when delivered by Hans Haacke in 1972, resulted in his exhibition at the Guggenheim Museum being cancelled. Hers is a broader inquiry about micro-economics.

Rosler is among a generation of artists that, beginning in the 1960s, produced un-sellable work in opposition to art markets: the dis-embodied, the ephemeral, the performative. Rosler’s Meta Monumental Garage Sale at MoMA is part of an initiative at the museum, formalized in 2006 with the establishment of the Department of Performance and Media Art, to present and acquire some of this formerly-ephemeral genre. Performances of forty years ago will necessarily be shown via preparatory drawings, film, video, or photographic records, or performance artifacts. This will not apply to work such as Tino Sehgal’s, where the museum acquires the rights to stage performances, and the issue of Marina Abramovic’s re-staging of her earlier work requires a separate discussion. History often leaves only fragments, and we make do.

Current work, however, is different. Is the Museum of Modern Art an appropriate venue? I realize an offer from MoMA would be hard to turn down. But should some art, intended to be seen in other circumstances, stay away from museums until it passes into history? While one hopes the curators consider the question, it is ultimately up to the artists. Perhaps Rosler’s Meta Monumental Garage Sale functioned as the artist intended for visitors who spend less time thinking about museums than I do. I have worked as a curator and teach museum studies, so I’m used to thinking about what museums exhibit, and how, as well as their funding problems. While I can’t accept Buren’s idea that museums both validate and bury artwork, I’m afraid that in this instance, MoMA was too intrusive a frame.