Post by Jaclyn Seufert

The works by Wangechi Mutu at Drexel’s Leonard Pearlstein Gallery inaugurate the gallery’s new space in the Urbn Center Annex with a bang. It’s a big show by an important international artist whose provocative works speak forcefully to issues of women’s empowerment and self-image. The show should propel discussions all over town.

Gallery Director Dr. Joseph Gregory told me it has long been his wish to give the Kenya-born, Brooklyn-based multi-disciplinary artist a show at Drexel, and this foundational show at the new gallery, with its high ceilings and almost 5,000 square feet of space, was the ideal moment to make it a reality. In another smart move, Gregory invited two local artists — Philadelphia Poet Laureate Sonia Sanchez and dancer and choreographer Tania Isaac — to respond to Mutu’s works in a performance at the opening. This combination of global and local at the opening was perfect.

Wangechi Mutu is concerned with how black African women are portrayed through the western lens. Her work also deals with issues of post-colonialism and poverty in Africa. Her collages, videos, installations, and sculptures are heartfelt provocations that strike you like a hammer blow.

Upon walking into the gallery I was struck by her largest piece in the show, Suspended Playtime. The installation, different from the collages, paintings and videos on display, stretches almost the entire length of the large high-ceilinged gallery and consists of hundreds of soccer balls made out of garbage bags bound and hung by twine from the gallery ceiling. The soccer balls, which dangle at knee-level, are those that children in Kenya create to facilitate their own playtime without actual balls or toys being given to them, but with the supplies they have available to them. The suspension may represent the cut-short nature of playtime due to the problems children face everyday. The interactive piece allows a viewer to walk through the installation. Being surrounded by these seemingly cold objects, foreign to me, forced me to see the reality that they represent playtime to these children.

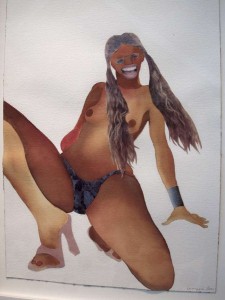

In an older series from 2001 titled Pin-up, Mutu references the posed, over-sexualized, and controlled visuals of the women known as Pin-up girls; specifically African pin-up girls. The images — which are small and combine drawing and collage — show women posed with their legs spread, asses-out, hands on hip, some with missing limbs, some with tails, some bloody, with exaggerated features; speak of the violence and victimization of African women.

The most interesting and technically impressive work in the show is The Ark Collection wherein Mutu explores what an African Woman actually looks like in the western world. The artist takes actual ethnographic photographs that are made to represent African culture, and collages them with pornographic images of African American women. The juxtaposition of these two types of images is visually very interesting. Initially I would think she was combining the reality of her culture (ethnography) with false representations (pornography). However, upon learning more about these collages it appears that the ethnographic photographs, taken by American photographer Carol Beckwith, objectify this culture through a western lens, and this realization is jarring to me as a white American woman. It forced me to wonder if almost everything that I have seen involving African culture has been presented through this Western Lens, and if so can an artist or photographer with no relation to the subject actually portray the subject in its true light? It bears mentioning that this series is laid out in glass vitrines that look like science museum display cases, as if to call into question the scientific underpinnings of all ethnographic imagery.

I must add here that as an artist who is currently focused on the image of women and how women participate in their own visual representation through “sexy self-shot” iphone photos and web-cam videos, this series in particular got me thinking. I wonder if the ability to pose and document yourself in these “selfies” makes for an accurate representation of who you are as a woman. Or do many women continue to pose in an over-sexualized fashion in the “selfies” because they are used to seeing it done this way? Most of the women we see in our own visual culture are posed and molded into the image intended by the artist, photographer, media outlet or corporation that is controlling the image. If the woman was in control, would she be more inclined to tell us who she is or will she continue to pose the way she is used to seeing women being posed by others?

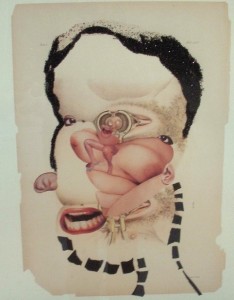

The Histology of the Different Classes of Uterine Tumors is another collection of the artist’s collages, this time imposing the distorted faces of African women on top of medical illustration pages showing tumors of the uterus. I first thought the images were textbook images of the female reproductive system since the tumors are not particularly unpleasant or disturbing as portrayed. But looking at the title of each tumor in small print at the top of the page tells you that the tumors are invasive and often-fatal malformations that just look benign in these textbook drawings. The exaggerated lips and distorted qualities of the African faces in the collages coupled with the tumors make a powerful statement about the standard of beauty that is held in the western world. This standard of beauty is one that is strong and brainwashing enough that it can eventually make any woman who doesn’t possess these looks and features feel as though she is diseased and disfigured.

Mutu’s four video projections, installed in a separate space with seating, show another more physical and personal side of the artist’s work. In the videos the artist herself portrays different sides of womanhood. There is the empowered woman in the video, Cutting, where Mutu viciously hacks at a wooden log with a machete; an angry woman in Shoe Shoe, where she is pushing a shopping cart up a street before she begins throwing shoes from her cart at the viewer; a dressed up diva woman with huge high heels who squats down in front of a tree and eats cakes with her bare hands in Eat Cake; and the laboring woman who is endlessly scrubbing a dirt ground in Clean Earth, Themes that seem to run through the videos are anger, abasement, perseverance and consumption.

As different as all of the work is, Mutu is consistent in luring her viewer in before she pounces, drawing you in with glittery surfaces and shiny magazine clippings or with mesmerizing video imagery. It’s all done in seeming perfection and is a wow of a show.

Wangechi Mutu, through March 30. Leonard Pearlstein Gallery, Urbn Center Annex, Drexel University, 3401 Filbert Street Philadelphia, PA 19104

—Jaclyn Seufert is a second year MFA student at The University of the Arts. Her current paintings explore issues of female self-presentation on the internet.